Mike Boissonneault enjoyed a 37-year career in the Canadian avalanche industry, including 15 years as the head of the BC Ministry of Transportation’s avalanche program. Originally from Ottawa, Mike’s introduction to the avalanche industry was at the Granduc Mine north of Stewart, B.C., in 1979. When the mine closed in 1985, he moved nearby to the highway avalanche program at Bear Pass, where he worked for two winters.

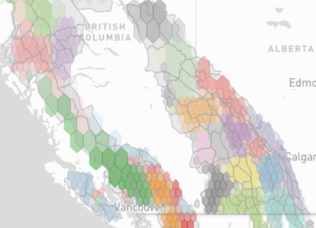

He enjoyed several winters as a consultant for mining operations before rejoining the Ministry of Transportation as the Senior Avalanche Officer in 1989. In 2002, he was appointed Manager of the provincial avalanche program. In those roles, Mike worked to establish avalanche safety protocols for the provincial highway network, which comprised of over 60 avalanche areas and 1,200 avalanche paths.

Mike assumed the Manager role shortly after the tragic deaths of two highway avalanche techs, Al Munro and Al Evenchick. He led the way in safety reforms to ensure there was never a repeat of that incident.

Mike was very involved with the CAA. He was Chair of Explosives Committee for eight years. His most notable accomplishment was securing CIL as a supplier of safety fuses after no other explosives manufacturers would work with the avalanche industry following a fatal hand charge incident in the U.S. in 1996. After months of contacting all possible suppliers, Mike reached out to Everett Clausen at CIL and secured them as an explosives supplies for the industry—a relationship that lasts to this day.

Mike was also prominent in the development of safe procedures in the use of 105mm recoilless rifles and 105mm howitzers used for avalanche control. He worked to improve and promote good working relations with Transport Canada, Federal Explosives regulators, and WorkSafeBC. This culminated in overhauling the WSBC avalanche blasting exams and CAA explosive training programs.

Mike served on the CAA and CAC (now Avalanche Canada) Board of Directors for six years. He was CAA Vice-president for two years when the CAA and CAC split and became separate organizations.

Mike left the highway avalanche program in 2016, but continues to work as a project manager for the Ministry of Transportation.

He was interviewed for the CAA History Project on February 22, 2024.

Hello, my name is Alex Cooper, and I am here on behalf of the Canadian Avalanche Association’s 40th anniversary History Project. As part of this work, we are interviewing key figures from the Canadian avalanche industry’s past in order to capture our association’s and our industry’s history.

Today, I am joined by Mike Boissonneault. Mike spent 37 years working in the avalanche patch beginning in 1979 at Granduc Mine. He spent many years with the BC Ministry of Highways developing avalanche programs across the province. He was chair of the CAA’s Explosive Committee for eight years and was a board member of the CAA and Canadian Avalanche Centre from 2006–2012.

And for his work, he was named an Honorary Member of the CAA in 2017.

Alex Cooper: Thanks so much for joining me, Mike.

Mike Boissonneault: Happy to be here.

Did I get that introduction right?

Perfect.

My first question, which I ask everybody is: when did you first become aware of avalanches? Whether it’s something in person or something captured in the media.

It was actually working at Granduc. I worked at the Canadian Outward Bound Mountain School for several years and that’s where I met Robin Mounsey. He was on the staff at the school as well and he had secured work in Stewart working on the Granduc Road. He offered me a position in 1979 and that was my first encounter. So, working on what could be arguably one of the most active avalanche programs on the planet at that time, an area that had previously recorded the most snowfall in one winter season at the Granduc mine site.

And a very historically significant program as well given the 1965 avalanche.

Exactly. That was one of the large avalanches—that and the North Route Cafe avalanche—so that northwest part of the province was notorious for active avalanche areas.

Definitely.

Can we jump back a bit? Where are you from initially?

I was born in Ottawa and I went to Lakehead University in a Bachelor of Physical Health program. I alternated between going to Lakehead University and working at the Outward Bound school. Like I said, that’s where I met Robin, and he offered me the position, and away I went. That was the start of my work in avalanche programs.

Did you grow up skiing or involved in winter sports?

Yeah, you bet. I was on the high school ski team. I didn’t do any downhill skiing competitively, but I did a lot of cross-country skiing.

Living in Thunder Bay, going to Lakehead University, there are several ski areas in Thunder Bay, so our so-called study week at university was more like a ski week. So, that’s where I got my start in winter sports and skiing.

How did you wind up out west with Outward Bound?

I was in the high school band. We had a school trip to Victoria,and then worked our way from Victoria to Calgary. Gosh, when was it? ‘71? And that’s when, just traveling through the mountains for the first time, I thought, “Yeah, this is going to be home someday.” And sure enough, it was.

As soon as I had the opportunity to head out west and work at the Outward Bound school, I took it, and I haven’t looked back.

What kind of work did you do with Outward Bound?

If anyone knows the basic philosophy, it isn’t so much a skills-oriented program, but character building and a personal-growth program done through activities. And those activities are things like mountaineering, technical rock climbing, kayaking, and group initiative tests.

At that time there were 26-day courses. That’s a pretty lengthy time to do those sorts of things. Lots of rock climbing, lots of kayaking. Robin Mounsey, he was an absolutely amazing whitewater kayaker. I did a lot of kayaking and just loved being in the mountains, living and working in the mountains.

What about winter activities?

There was one season I got involved with a program called Ski-cade, and that was to try and promote and educate mainly high school kids about the pleasures of skiing. I spent one winter travelling the province with another fellow in a van and putting on little ski clinics at high schools all around the province. That was good fun.

You said that going to Granduc was your first experience with avalanches. How did you get that job? Was it just knowing Robin?

Robin Mounsey offered me the opportunity to go up there. Of course, I didn’t hesitate. It was good timing because I just graduated from Lakehead University and wondered what am I going to do this coming winter when I would otherwise be going to school. I found myself driving a beat-up old 1957 Ford half-ton pickup to Stewart and I worked on the program with the likes of Robin, Hector McKenzie, and Alan Dennis. It was a great group to work with and the town of Stewart was a beautiful little town at the time. It has a rich history of mining activity and I just loved it. It was a small town. At the time the population was maybe 1,000 or 1,200 people, but it was a great little town and wonderful to be involved with the avalanche program there.

What was your work like at Granduc? What were your reactions to being in that environment for the first time?

It was a program that worked 24/7. We had a shift work. You worked a series of day shifts and then got a couple off-days, and then afternoon shifts, then graveyard shifts. The intensity of the storms was beyond anything I could have ever imagined or had ever seen before. Being at that location, the storm cycles were pretty severe at times, and the snowfall intensity rates and depth of snowfalls you would get from any typical storm were pretty impressive.

It was a pretty steep learning curve. Between Robin, Hector and Alan Dennis, you learned a lot in the early seasons. I really give them full credit for showing me the ropes in the early stage of my work in avalanche programs.

What kind of training did you did you get? I’m always curious about what training people had in these years.

Well, that was back in the day. There weren’t a lot of formal avalanche training programs going on. The Avalanche Association was, I’ll call it, in its infancy and just developing their training programs. But it was pretty much just learning from the folks that had been involved in that work—mainly from Robin. It wasn’t until I started work with the Ministry that I started taking the more formal training courses with the CAA—Level 1 and then the (Level) 2—and carried on from there.

What were your responsibilities at Granduc?

Keeping the road open. The priority was during the times when the ore trucks would run, and during the morning and afternoon shift changes. The priority to keeping that road open was it had to be open more-or-less between six and nine in the morning and then from four until six in the afternoon. The focus of doing all the control work was around those time periods and the primary method of control was a case charging—just putting a bags of ANFO on the shoulder of the road and detonating that charge. We were fortunate most of the slopes above the Granduc Road could be affected by a case charge. It wasn’t until a few years that we eventually got a recoilless rifle. We got a couple of recoilless rifles. We had a 75 recoilless and then eventually a 105 recoilless. The odd time we’d do some heli control, but it was a really active program.

We went through tons and tons of explosives on a seasonal basis. Back in those days, we didn’t have the requirements of the kind of security of storing explosives. All our powder was stored in plywood shacks on the side of the road with a 3303 key that probably every construction worker in the northwest had at the time. There were often times we’d show up at the so-called powder mags and the porcupines would have eaten the side of the shelter, so you could see ANFO spilling out the sides of the shelter sometimes. It was a different era in in the concepts of storage and transportation of explosives.

I’m curious—this is the time when the CAA was just forming. How connected were you guys to the Canadian Avalanche Association? I mean, you’re pretty isolated up there.

We certainly knew about it. Robin was the main contact and he always encouraged us and others to become involved and take on a professional role as you could. That’s what the CAA at the time was supporting and promoting. We got on board and I joined the association. Well, it wasn’t until I left Granduc that I joined the Association. When I started with the Ministry program in ‘85, that was the time of my membership. I’m not sure, but I think I was somewhere in the mid-30th member of the Association at that time.

Did you go to any of the early meetings before you became a member?

It wasn’t until I started with the Ministry program in ‘85 that I actually showed up for any of the CAA meetings.

What about courses through the CAA? When did you take those?

I took my Level 1, and I believe that was in ’85. At the time Peter Schearer, Chris Stethem, Jim Bay, folks like that, they were all instructors at the time. It was a pretty impressive group of folks providing those courses and leading them. I was really fortunate that those folks were we’re taking the lead and providing some educational services for the people interested in the industry at that time.

What appealed to you about avalanche work when you were getting into it?

Certainly, at that time I just loved extremes in weather. I remember at times starting a shift on the Granduc program that involved driving in a crew cab from the town of Stewart up to our little shacks at 10.5 Mile. There were times driving up there that the snow was so deep that it was flowing over the hood of the vehicle. You were just plowing through the snow. It was just an excitement about being in really severe weather that attracted me.

It was interesting. After a couple of years, I hoped it’s going to snow like hell on this shift. I just wanted to be out in it. After a couple of years of that, it was trending towards, “I hope the moon’s out and the stars are out and it’s a nice clear night and I can just sort of relax and go on a couple of patrols.”

Funny how your attitudes change.

Oh, I’m sure.

I just loved being in the extreme weather elements like that.

Starting out, did you ever have any good stories or close calls or notable incidents?

I don’t think anyone involved in this industry can claim they’ve never had a near-miss or a close-call. We certainly had those on the Granduc program. It was in the early stages of protocols and procedures for deploying or using explosives. Back in the day, we cut our fuse lengths to what we thought was a reasonable length. You wouldn’t be doing them that short nowadays, that’s for sure.

There was one time in particular where I set the charge, I lit the fuse, and then I drove to my safe location. There’s a piece of equipment on the other side that blocks the road, and wouldn’t you know it, once I turned around, there was an avalanche that had crossed the road and I had to do a three-point turn on next to no width of a road and drive past the burning fuse with the 50 kilograms of ANFO. Fortunately, that didn’t go off while I was driving by.

Wow!

I wouldn’t do that again.

No.

We’ve all had close calls. Another time, we’re out ski touring—this is early in my days. I remember Robin saying, “Just a little more to the right and I’ll get a picture of you skiing down the slope.”

I thought, “Really? Are you sure? Is this safe? Because it’s a lot steeper over here.”

Of course, on my second turn, I got caught in a size two slab avalanche and came tumbling down.

I think experiences like that, you’re fortunate to survive. Of course, I ended up more-or-less being on the surface and just had to be partially dug out, but it gives you a healthy respect. Rather than just go through your early stages and never have any close-calls or near-misses, I think if you have those—and you’re going to—you develop a far better attitude about personal safety and safety for others that you’re out there with. Even though it was a near-miss and a close-call, in some ways it was a fortunate thing to have happened.

I imagine experiences like that would have informed things you did in the future in your career, even looking at a brief outline of what you accomplished, which we’ll get into.

You joined the Ministry of Highways back then with the Bear Pass program in ’85. Was that a new program when you joined?

No. That was actually a program Alan Dennis had been working on for a number of years. Before his involvement, the Ministry avalanche programs back then was pretty much a road foreman or a maintenance worker doing patrols. If there ever was a natural avalanche on the road, then that’s what would trigger a closure.

Alan Dennis really began the Bear Pass program with an eye to actually trying to forecast and predict avalanches before they occurred. So, good for him to have started the program. When I became involved was when the Ministry program was just starting to develop remote weather stations. A big part of what I was doing at the time was working to install remote weather stations in and near the avalanche start zone areas.

It was also when I started with Bear Pass, because of my background at Granduc at the time, that we initiated some case charge locations in one particular spot called Summit Sluffs. They’re low-elevation start zones, but a really active area right across from where the Bear Glacier is. That was the first explosive avalanche control that had been used in the Bear Pass. Prior to that it was just preventive closures.

OK. That’s what I was wondering. How much was it reactive versus proactive work? You would have been part of that transition to being proactive about shooting for everyone, limiting closures of course, with much more limited tools than they have today.

What were the tools at your disposal?

Like I said, back in the mid-80s, we started doing case-charging work there. Eventually we did get a recoilless rifle and that was at the Windy Point area, the more eastern part of the Bear Pass area. That was the other quite active area. And then, given the elevation of the avalanche paths in the other spots, we began doing some helicopter control. Doug Wilson was a big part of that program that developed some of the helicopter control, and working on the artillery program as well. He was a big part of developing programs in Bear Pass throughout the late-80s, early-90s as well.

Yeah, those are monstrous avalanche paths up there.

They’re really big. And it isn’t just the mass that can get to you. It’s the wind blast preceding the avalanches. There are a number of spots where anyone that’s driven through the Bear Pass, you might wonder, where’s all the trees? They all got blasted away with some of the large avalanche cycles.

Yeah.

Around this time was when you became a member of the CAA. Was that when you joined the Bear Pass program?

Yeah, that’s right. When I joined the Ministry, that’s when I became a member. In fact, I was just looking at the letter that Peter Schaerer wrote. I recall at the time he was saying basically, “Welcome to the Avalanche Association, and the dues are $20.” So, I handed over 20 bucks.

What kind of work was the CAA doing in those days?

I think they were working to develop training programs. Mainly, Geoff Freer and David McClung and Chris (Stethem) and those folks were involved in developing those training programs. Like I said, once those programs or courses became available, I think it opened the door for a lot of folks doing this kind of work, that they weren’t just trying to figure things out or learn from someone else. You actually had someone that had a lot of wisdom and experience and familiarity with how to do things properly.

You would have taken your Level 1 in ‘85?

I think it was ‘85 or ‘86 in in Creston. They did a lot of the training programs there. It was reasonably near Kootenay Pass, so a lot of the field days were just drive to Kootenay Pass, and then the classroom work there. That was a good location. And it was near Kootenay Brewing, so they always had our brewery tour during the course.

How involved were you with the CAA when you when you first joined?

Oh, not much really. I certainly appreciated and supported everything that they were pursuing. It wasn’t until I’d been working in Bear Pass and then ended up in Victoria working as the Senior Avalanche Officer that I became more involved in the CAA.

How did your transition go? You’re at Bear Pass for a few years and I understand you did a few years as consultant with some mines.

That’s right.

And then and then you went to Victoria. Can you tell me a little bit about the mining work you did?

There was a lot of mining activity going on at the time and Robin Mounsey had done a lot of consulting work for mining outfits. Around that time his focus was mainly working on movies—setting up site locations and doing safety work for movie outfits. It left a bit of a gap in who’s going to provide avalanche consulting service for these mining outfits. So, good timing for me.

The challenge for a lot of the mining outfits at the time is that they really didn’t acknowledge or recognize that some of the mine sites and the buildings that they’re trying to construct might be within avalanche terrain. I had several mines on the go at any one time. I provided training programs for all the staff and provided some advice about where they might be able to work safely and under what kind of conditions, and would do control periodically for them. I did that for three winters.

I had a lot of support from the some of the mining inspectors because they would do inspections of mines, and then they would often write up a requirement that you need to have an avalanche assessment provided. And back in those days, if you had some kind of experience and familiarity with that kind of work, that was recognized as, “OK, you’re qualified to do this.”

So, yeah, that was that was a really interesting time. Lots of time in helicopters flying back and forth between mine sites. You’re just finished one visit at a site, and then I’d be home for a day or two or three, and then off to another one. It was great that I saw the diversity of all these different areas.

I also had an opportunity to work at Canada Tungsten mine in the Northwest Territories, and did the avalanche work for them as well. It was a real contrast in climates and snowpacks between working in the middle of the Northwest Territories and then Northwestern B.C.

No doubt. Were these active control programs you were involved in, or is it more just advising where mainly (avalanches) might happen?

Mainly doing advice and doing the odd bit of control as and when required. But my focus was on trying to prevent, stay away from the avalanche terrain. It was typically, I’ll call it during a spring cycle. If I did any control back then, just remove the hazard before the spring and summer operations. You would think intuitively someone might realize don’t put your building at this site, but in many locations, that’s where there were no trees. Folks that were developing mine sites would go,

“Oh, here’s a good spot to put the crew barracks or the kitchen or whatever.” Just because there’s no trees there, doesn’t mean it’s a good building site. Why do you think there’s no trees? Look up!

You ended up in Victoria in ’89? Does that sound right?

Yeah. That job was the Senior Avalanche Officer. There was a job posting, so I applied for the position. I think the first round of interviews, nobody got selected. They had another round of interviews and that’s when I got the position. I was working with Jack Bennetto, who was the manager of the program at the time, and it was a great group. I really enjoyed working on that program.

Once again, just having the opportunity to go to eight different avalanche programs around the province. and having some similarities and get uniqueness between them. To me, it was the perfect blend of working in the avalanche industry and having the opportunity to work in an office location, develop some procedures and protocols, work with the provincial and federal regulators on how best to manage programs, and then spending time in the field.

I always wanted to make sure that I didn’t lose contact with field work. Even though I was in some respects not working actively forecasting at that time, I always felt that if I ever had to, I could go to any of these programs and be a reasonably decent forecaster and look after things. I always wanted to make sure I got to each of the eight programs at least twice a season, so, a lot of travel.

That’s great. When I interviewed Jack Benetto, he described this as “paper avalanches.”But would you say you were quite involved in the field as well?

Yeah. Like I say, that was a focus that I really wanted to maintain that. My background was heavy field involvement and working on really active programs. For some programs, that might be a little less active and involved. I came from programs that were just intense, there was always something going on. I didn’t want to lose touch with the field work. I always maintained my blasting certificates, first aid courses—all the certifications that would be required to be an active forecaster. Even though I didn’t necessarily need them for working on “paper avalanches,” but I always felt I did.

I covered a number of times for various reasons if someone in the field was either short-staffed, or unavailable, or there was a big cycle going on, or they were just getting tired. “OK, I’ll be there tomorrow, I’ll be there later today.” I really enjoyed staying involved in field programs even though I was working in Victoria headquarters.

I’m really interested in how the highway programs evolved over the years. You would have come on board—well, in this position—probably 10-15 years after they were started up. What kind of procedures, policies, systems did you have in place? Maybe even get into the infrastructure in terms of weather stations and so on.

There was a lot of development going on to automate our weather stations during that time. When I first started with the ministry, the roadside weather stations were manually read. They were not even read by avalanche staff. They were read by truck drivers that were very reluctant to get out of their warm vehicles and get snow in their boots, so the quality of the data back then was somewhat suspect.

My initial involvement with the Ministry programs was at the time, when we were developing not only remote roadside stations, but remote weather stations at start zone locations. That was a huge undertaking to try and automate all this information, and then create a daily collection program so that you had real-time data that really helped out with the forecasting rather than some suspect data that, how much can you rely on it? Did it really snow this amount or not? I was involved in an effort to develop those automated weather programs.

We had a lot of policies and procedures you know—and this is where Jack would be talking about paper avalanches—that just given the nature of being a provincial program, we wanted to be an industry leader, we wanted to set the standard. We’re always working to try and ensure that our explosive procedures, for example, or our safety plan that we had back in those days, was as robust and cohesive and complete as possible. But my take on that was that you can never develop a protocol or a procedure, a standard, a guideline and just go, “Yeah, we’re done. It will always be like that.” I always wanted to ensure that as new information became available, as regulations evolved or changed, that we adapted and made improvements.

That was a big push that I was always wanting to pursue, that we have to renew and review our procedures on an annual basis rather than just go, “Yeah, we got an explosives procedures plan and we’ll never look at it again. You have to always be making sure that you’re compliant and current with the industry best-practices and prevention and federal regulations.

What were the training programs like back then for highway avalanche workers?

We had pretty stringent training programs. For our avalanche forecasters or lead forecasters, that was a requirement they had a minimum Avalanche Operations Level 2 at the time, which was the standard at the time. If you have a Level 2 back in those days, you had sufficient experience and wisdom and familiarity with how to determine what the hazard levels were and how best to manage them.

There was a long list of qualifications that if you wanted to be a ministry avalanche forecaster, that you were pretty well established in the industry. I think the fact that our avalanche staff, there was virtually no turnover, I’ll bet, for probably a good 15 years. Folks like John Tweedy, Dave Smith, Ed Campbell, Bruce Allen, all these folks that were involved in our programs at the time, that once those positions were secured, they were a lifetime appointment pretty much.

Were there any expectations around annual training or continuing professional development?

That’s a good question. Probably not so much in the early years, but as that became more and more recognized, that’s something we really felt strongly that you just don’t sit back.

I got my Level 2 back in 1990 or whatever it was, and now there’s all these refresher courses and this continuing professional development that we really encouraged our folks get involved. Just because you’ve got a ton of experience and you took your Level 2 20 years ago, doesn’t mean that you don’t participate in these continuing professional development programs. We pushed that hard.

Going to Victoria, I guess would have brought you more in tune with the rest of the industry and the CAA. You mentioned becoming more involved with CAA as you joined that program, went back to highways.

I think the CAA was doing superb work. I always encouraged participation in the annual general meetings and I got to say that was a challenge because we always tried to have the ministry program year-end meetings at the same time as the Avalanche Association meetings. It wasn’t so bad when the CAA meetings were the better part of two or three days. It all depended if you were on various committees, but for the AGM, back in the late 80s or throughout the 90s, it might only be a two-day event. We could always squeeze our ministry year-end meetings in that same week. It became more and more difficult as the CAA lengthened the duration of their meetings. That would pretty much go Monday to Friday, especially if you’re involved in some committees or the avalanche training schools.

We always pushed hard for active participation in the CAA meetings and getting people involved in in in committees, rather than I’ll just pay my dues and then carry on. It was really important that people do more than just pay their dues and show up five days a week on your program.

For sure.

I’m really curious, 1991, I believe, is when InfoEx was started—’91 or ‘92. I was wondering if you could tell me what it was like getting involved with InfoEx and taking part in all that.

I think that was a great initiative. Sharing information only improves everyone’s ability to know what’s going on, not only in your own patch but in your neighbours’, whether it’s the north, south, east, or west. We were a really strong supporter of that. I covered subscription fees for all the field programs, plus Victoria. I just thought, “This is a good way to provide a financial contribution to support InfoEx.”

Everyone used it. It was a really good source of information. Chris Stethem was a huge part in developing that, so kudos to him for getting that off the ground.

Was there much information sharing happening before InfoEx started?

Probably not as much as there should have been. That was a real positive step in the right direction to get that done.

I’m curious—was it hard to get your staff to buy in? It’s a little bit of an extra step at the end of the day.

I think most of them bought into it. There might have been the odd sort. I mean, the general character of folks in this business, the stubborn streak sometimes runs in some folks and I’m just going to carry on doing things the way that I’ve done it for the last, who knows how many years and it seems to work. So, maybe there was some minor resistance in some programs, or they didn’t feel there was value in it. But certainly for the more active programs, I think they welcomed the opportunity to know what’s going on next door and to share their information as well.

When did you become involved with the Explosive Committee with the CAA?

Boy, when was that? I can hardly recall.

I couldn’t find an exact date. I’m thinking probably mid-90s.

Yeah, that sounds about right. Probably mid-90s.

I had a fairly strong background in handling and dealing with explosives, and was becoming more and more familiar with other types of programs and how they deployed explosives. I certainly felt at the time that we should all be on the same page here. If we’re going to deploy explosives from a helicopter, there should be some kind of uniformity and consistency in how we do those kinds of missions. I really felt there should be some kind of commonality between all the various types of explosive work. I welcomed the opportunity to be involved in the Explosives Committee and worked to develop training programs for the various disciplines for hand-charging, case-charging, and heli-control.

We eventually developed courses for that, and even tried to convince some of the American programs that here’s what we’ve done, you should give this some consideration as well. I would often get a bit of a blank look about you crazy Canadians.

The Avalanche Control Blasting course, my understanding is it was developed in the early-2000s. What inspired that development to have a course focused on avalanche control blasting?

Like I said, just the belief there should be some commonality between different disciplines. That even though we may be a highways program or an industry program, that whether you’re in a ski resort or a heli-control program or heli-ski program, that if we’re going to fly around in helicopters with the door off in a ship full of explosives, that we should all be doing something similar because WorkSafeBC would be all over us.

If they realized each program had a different procedure—and in order to get their approval, you had to submit your procedures to WorkSafe to get their approval—I really felt it was important that if they’re going to receive applications from the various types of programs that they have some similarity between them.

When I was running the Explosive Committee, we had a lot of meetings and my feeling was we invite other participants from the various disciplines. When I ran the Explosive Committee, I wanted to have someone from the heli-ski program and someone from the ski resorts. I wanted to have a real diverse package of people so that we had good representation. Bernie Protsch was on the committee as well and made a huge contribution to the development of training programs for the various types of deployments.

Then I felt that we also have to have someone from WorkSafe. That’s when we invited the folks like Gary Crowler, at the time, and Steve Duffy, and all these tough folks from WorkSafeBC. I think it made a big difference because up until then the attitude from a lot of the WorkSafe inspectors was that you guys are a bunch of cowboys. Once we brought them on board and showed them what we’re doing, and that we’re pretty serious about trying to make sure that we do all this safely, according to all the protocols that have been established as being safe. Provincial and Federal regulations, that we abide by them. I think it really helped out in a better understanding between WorkSafe and our industry.

I remember one time taking one of the WorkSafe inspectors on a heli-control mission with Scott Aiken, our avalanche tech out of Whistler overseeing the Duffy Lake program. I invited him along to go to do a heli-control mission. “I’d like you to sit in the back seat and you can see what we’re doing.”

That was the first time as far as I’m aware that a WorkSafe inspector had actually been in a helicopter while we’re doing a mission. I remember meeting him in the coffee shop and he had a spring jacket on, a little windbreaker, and a pair of running shoes and jeans. I said the door’s going to be off the helicopter, it’s going to be cold. He kept going, “Oh yeah, I’ll be fine.”

I remember we did the mission with him, and when we landed the machine, his teeth were chattering. He was red as can be. He was half frozen. We were asking him, “Are you satisfied?” He was chattering, “Yeah, I’m OK. Just keep on doing what you’re doing.”

That was funny. It’s really important, if you’re working with an industry regulator, bring them on board.

Was it difficult to build consensus when you’re working with so many different programs? To say, “This is the way we’re going to do helicopter avalanche control,” and they might all have different ways or slightly different ways of doing it. Was it hard to build that consensus?

Yeah, I would say initially, but I think everyone bought into it. We did run a beta course for the explosive course in Revelstoke. It was really well attended. We did a mock trial, we had presentations with the training materials. Clair Israelson was a big part of helping us out with that. We hired an explosives consultant, Gerry Silva, I think was his name, and worked long and hard to develop training programs for the various types of control. Then WorkSafe agreed that when they issue a blasting certificate in the future, it would have these various endorsements.

Oh! I remember my first blasting ticket. It was basically as if I was an underground mining blaster. That was that was all they had at the time. The Avalanche Blasting Course involves some basic avalanche knowledge to ensure safety, and then the various disciplines for, say, now you’re endorsed for helicopter control, or hand-charge mission, or case-charge.

We even had an avalanche segment as well. We broke down all the various types of avalanche control that you could do and then you would get an endorsement from WorkSafe on those specific disciplines.

Did you teach that course?

I oversaw the development of the training programs, but I didn’t teach them. Back in the day, I was teaching Level 1 courses a fair bit and it just got to the point where you can only do so much with your time. So, no, I didn’t teach any of the explosive training courses.

Another major development while you were with the Explosives Committee was—and you can fill in details here—this incident at Big Sky ski resort on Christmas 1996, where I believe a patroller died as a result of a hand-charge incident.

Hopefully I’ve got that broad outline correct. That seemed to have led into huge problems for the industry in terms of securing explosives, or at least safety fuses. Can you tell me like what happened there, and the fallout?

Yeah, Christmas Day ‘96, Big Sky and this ski patroller, fairly inexperienced from what I understand, doing what she thought was the right thing to do, or what had been taught to her. From what we understand, very short fuse links and apparently she made three attempts to light a fuse in very, very windy conditions. There was a big storm cycle and she couldn’t recognize that the fuse was lit, even though it was lit on the first attempt. They kept making multiple attempts to light the fuse. A terrible tragedy.

Ensign-Bickford at the time was the supplier of safety fuses for both American and Canadian avalanche programs. We got notice that Ensign-Bickford would restrict the sale of safety fuses to Canadian avalanche programs, so we were effectively cut off from the supply of safety fuses.

We got through that season, but that was a big part of what myself and Bernie Protsch—at the time he was involved in the Explosive Committee as well—on a near-daily basis throughout that following spring, summer, and into the fall, it was Bernie and I doing everything we could to secure a supplier of safety fuses. We went everywhere. We tried accessing fuses from various American outfits. They all said no, the liability is too much, the risk is too high. ”You folks are too high a risk, sale volume is too low to take on that kind of risk.”

We tried to secure a fuse supplier from Mexico. It was at a man-start fuse that we actually used a bit of but the reliability was terrible. We found a fuse supplier from Chile, but once again the quality and the workmanship of the fuse was poor.

It wasn’t until we approached a fellow who had been the previous federal explosive inspector—Everett Clausen. I remember the phone call with Everett—he was with CIL Explosives at the time in Montreal. I explained the situation to him over the phone and after a bit of a pause and silence, he responded with, “Yeah, I think we can help you out.” That was the beginning of a really good quality fuse supplier from CIL.

Everett is still with us and was actually at the CAA meetings last spring. For anyone that knows him, he is one of the most entertaining gentleman you could ever hope to meet. He makes a presentation every annual general meeting, and it’s a bit of a highlight of the week I would say, just hearing what he has to say. He has contributed a portion of the revenues from the sales of explosives and fuses back to the CAA. He has been a tremendous supporter and I can’t thank him enough—and our industry can’t thank him enough—for helping us out at a time when things were getting a bit desperate. There’s so much use of safety fuses—maybe less now because we have remote control systems in place in a lot of programs now—but back then, without a reliable safety fuse supplier, that would have shut down a lot of programs.

Oh, no doubt. I didn’t know that’s when the relationship with CIL started, that it goes back to that that work and then yeah, it’s amazing how it’s almost 30 years now. Amazing.

Am I that old now? It seems like yesterday. Wow!

That’s a huge deal to secure that partnership that’s ongoing, so kudos there.

And I thank Bernie Protsch for his help in making that happen as well.

I guess this is important, obviously for the Ministry of Highways, but also for the whole industry.

You became manager of the provincial highway program in 2002. This would have been following Jack Bennetto, right?

Yeah.

One thing I’ve noticed is this was not long after the deaths of Al Munro and Al Evenchick. How did that incident impact you personally?

That was pretty tough. I remember the phone call from Tony Moore, who was the avalanche tech in Bear Pass at the time. He called me at, I don’t know, seven in the evening on the day of that accident. He says, “Mike, I got a call from the maintenance contractor and Al’s truck is still parked on the side of the road.”

How could it be? I had just recently come back from a field trip, and I only went to Bear Pass. I didn’t go to the Terrace program that the Als worked on. I’d already spent the better part of a week in Bear Pass and I was heading back to Victoria, but as I was heading back to Victoria, I got a call from Al and he said, “Hey! We’re heading up to Ningunsaw. Do you want to come with us?”

I said, “I’m already on my way back to Victoria.”

I still to this day feel a bit guilty that if I had said, “OK, yeah, I’ll turn around and head back and spend some time with you in Ningunsaw Pass.” I’ve always wondered—would they have skied that slope if there was a third person with them? I wasn’t their boss by any means, but I was in the senior avalanche position. I’ve always wondered might they still be around if there was a third person with them rather than just the two of them.

They were phenomenal skiers. I’d spent a fair bit of time on previous visits with them. They were absolutely gifted. They could ski the most challenging conditions and make it look easy. They, like everyone in the day, if you’re going to be in the field, you might fly up, but why would you fly down when you could otherwise ski?

That was a real tragedy. Both left wives and young families. When I became the manager after that accident, it was a bit of a pledge I made to myself that we’ll never see something like this happen in this program ever again. I would encourage the field staff that you can still spend time in the field and do all the work you need to do, but don’t be taking risks.

In the aftermath of the investigation, it was pretty clear this was some pretty challenging terrain they were exposing themselves to, and it appeared they were skiing side-by-side down one of the more active paths in the Ningunsaw Pass. Perhaps that wasn’t an uncommon thing to do back in the day, but it sure opened the eyes to our industry and the CAA that we needed to do something to make sure things like this don’t happen to anyone else in our industry.

That was, I believe, the start of the expansion of the Level 2 programs into the various components, that we need to consider human factors. It isn’t just about digging holes in the snow, looking at layers, and looking at crystal types and how well they may be bonded to one another. It’s also considering the human factors. It’s after that accident that we can’t kid ourselves anymore, that we’re all exposed and subject to the so-called human factors that play a role in how determined someone might be to ski a particular slope. Even experienced folks like the Als, they both had 20-plus-years experience in the business and yet a terrible accident occurred for them.

I think it was a wake-up call not only for the ministry program, but for the entire industry, that be careful what you’re doing out there and really think long and hard before you make a commitment to a slope that you might want to go down.

Yeah. It’s really sad to reflect on the burden you mentioned you carry.

We certainly did what we could to acknowledge and recognize the contributions they both made. They did a phenomenal job in running the Terrace program.

There’s a monument. Myself and Jack (Bennetto) and Gord Bonwick, the other Senior Avalanche Officer at the time, we organized a ceremony. We had our year-end meeting in Ningunsaw Pass that year and we all flew up to the summit of the Ningunsaw avalanche area and we placed a monument—it’s still there—and had a bit of a ceremony on the mountain peak for them.

I didn’t know about that monument, but that sounds great.

It’s still there. I visited many years after we put it in place and it looks like the day we put it in. Whatever paint was used on it doesn’t fade. For the rare person that might be at that location, they’ll see a pretty impressive monument for those guys.

Very nice.

What kind of changes did you implement in the program after that in terms of safety training and what not?

That’s when we initiated the requirement for the field staff to carry SPOT units. There was a bit of resistance there because it felt like, “Oh, you’re tracking where I’m going and what I’m doing.” It was to say, “This is for your safety and protection, we want to know where you are.”

We had the ability to see on a computer screen a little dot that would be moving along so that we knew where you were, because nobody knew where the Als were after that accident. They had transceivers, and it was Tony Moore that was doing a transceiver search from a helicopter and picked up the signals in the debris at the bottom of the slope.

We initiated everyone carrying the SPOT units and had a pretty robust protocol for identifying where you’re going. If you’re doing a field trip, what was the reason and the purpose for it? How many in the party? When are you expected back? All this would be communicated through the ministry radio room. Once you completed your field work, you would call in and say, “I’ve returned.”

We didn’t have a protocol like that before Al and Al’s accident. Maybe some folks, that’s a little too much monitoring what I’m doing and where I’m going. But when the consequences for something going wrong can be fairly severe, this is just a basic protocol that you’re going to have to accept.

I’m pretty sure they’re still doing that now. That’s certainly something I pushed hard to establish. It’s just basic industry standard now, that you’re going out in the backcountry, tell someone where you’re going, when you’re expected back, and what the purpose of your field work is.

The industry—even recreational standard—not everybody does that, but it’s the smart thing to do.

You said you wanted to make it your mission to never have another incident. There hasn’t been another incident so far. That’s something you can feel proud of, I hope.

I want to get into you joining the board of the CAA in 2006. What inspired you to join the board? Actually, when you joined it was not just the CAA, it was also the Canadian Avalanche Centre, which had been started a few years before, so joining that joint board.

Well, I got nominated and silly me, of course I accepted. I’ve always felt that I’ll be as active and engaged in our industry as I can possibly be. I remember after I accepted folks coming up to me going, “Are you crazy? You can barely keep up with what you’re doing!”

I just thought this is a great privilege and an opportunity, so I’ll take it on. Back in the day—who knows if it’s still going on now—trying to recruit people into those positions was pretty tough, especially taking on any of those board positions, and especially being either the Vice or the President position.

Usually there’d be a break before the nominations and there’d be a bit of arm twisting going on in the hallways about would you take this on, or you. It was or whoever succumbed to the pressure of, “OK, I’ll accept the nomination.”

I was happy to do it. At the time I was told, ”Don’t worry, it’s only one phone call a month, that’s all you have to do.” Of course, It was far more than that.

It was quite an honour to be nominated and work with some other really active and dedicated folks in in the business. I’m happy to have taken that on.

I guess Steve Blake would have been the President at the time.

Yeah.

And you were the Director for Professional Members.

Yeah.

What did that role entail?

Oh, gosh! That’s just doing your best to represent the interests of the Professional Members—promoting training programs, maintaining your ethics, your code of conduct. Just doing my best to represent that group.

What do you remember the big issues were? We’ll talk about the CAA side. I did interview Steve Blake.I understand there’s a lot dealing with scope of practice and who could be involved with avalanche work. Were you involved a lot in those discussions?

I’m probably being a good listener at the time more than anything. I think there were some concerns at the time some folks may have been taking on levels of responsibility above their competency levels. There were some folks that seemed to like interacting with the media at the time that may not necessarily have represented the interests of the Association. There were some concerns about individuals like that, but that’s one or two or three people out of the entire group.

There was a push that whatever work you’re going to take on, ensuring you had the qualifications and competencies to do a good job of it.

Also, my understanding is demonstrating that you know a lot of these avalanche professionals who, maybe they’re not engineers but are still, very capable of doing a lot of the work that it comes with working in the field.

Well, there’s a small group, as I’m sure we’re all aware, that can nowadays take on that kind of work determining impact pressures, maximum run-outs—that’s the work of an engineering group, not of just a practitioner. So, trying to identify where those boundaries are and get some recognition. Here’s the folks that are qualified to do these kinds of works. The engineering work that folks like Peter (Schaerer) would be doing, or Bruce Jamieson or Alan Jones or Brian Gould. Those are the folks that can take on those high-end determinations of maximum run-out distances and impact pressures.

You’re probably aware that one of the courses that was going on around that time was we had the various components of the Level 2. There was the introduction of the hazard mapping course. There was a Level 1 and a Level 2 for hazard mapping. They had one of the advanced hazard mapping courses in Revelstoke, and the instructors were David McClung and Peter Schearer. Janice Johnson worked on that as well. It was like going to university—a lot of calculus, a lot of formulas. I remember being on that course with the likes of Brian Gould, who hadn’t established his business yet, but he was pretty much fresh out of engineering school. I remember even Brian shaking his head and going, “Man, this is hard.” They ran that one course and haven’t done one since.

For yourself, you have your university degree.

I went in the 70s. I had a bit of a vague memory. I kind of remembered some of this stuff, but it was a long time ago. Of all the courses I’ve taken in that industry, that was the hardest. That was brutal.

It sounds bad. I did a year of engineering school and I have vague memories of calculus and physics.

Of course, for someone like David McClung, this is just easy-peasy for him. He put up these formulas that would go from one end of the chalkboard to the other and kind of go, “What’s your problem? This is easy stuff.” No, it’s not. Maybe to you.

No, David was great on that course.

We talked a bit about some of the CAA challenges, but the Canadian Avalanche Centre had been started up in 2004. You would have joined the board when it was still in its infancy. What was your role in terms of directing the work of the Avalanche Centre?

I don’t think I would say I did any directing. Once again, just involved in all the meetings and a recognition that there had to be some separation between the CAA and the CAC. As Ian Tomm would say at the time, bifurcated, that we’re branching. We had to ensure we’re providing a service to the public, and also service to the professional members. Both programs were growing so much that we had to find a way to separate them.

That was a challenging period. Clare Israelson was a big part of working towards that. If you want to call it my involvement, I did at one time recognize that there’s some real challenges here in trying to create this separation. I helped out with a fellow that had provided a training course for the ministry program about governance. Nothing technical with avalanches, but just a human resources advisor, and he provided a session for the CAA/CAC staff at the time. I hope that helped at the time create some smooth transition from the CAA and CAC being one organization to splitting them into two separate outfits.

My involvement? I just recommended to get someone that can help us out rather than us trying to figure it out ourselves. This fellow, I thought he was superb in helping us achieve that.

Who was that?

It was a fellow named Peter McCoppin.

I haven’t seen that name.

He’s pretty well established in putting on these kinds of courses.

OK.

You would have come on the Board when Clair Israelson was the Executive Director for a couple of years.

Yeah, replaced by Ian Tomm.

I guess at that point you had discussions on needing one person to run each (organization).

Yeah.

I guess Joe Obad would have come on board.

Joe Obad came along. I was involved in the interviews for Joe.

He’s still around. He’s doing a great job.

Good for Joe.

Back in the day, we always felt that anyone in a position like that has to come from a practitioner’s background. We came to realize that we need good managers. Joe came from a good background of management. He got the nod and is still there, obviously doing a good job.

He’s been in a position for probably a dozen-or-so years now. He’s my boss. He’s great. He treats me fairly. He treats me well. He’s fun to work with.

I forgot something to ask you. Something about highways that I’m interested in was the establishment of the remote avalanche control systems around the province. I thought those were more recent innovation, but then I see the first GAZEX systems were installed, I think it was in the early-90s.

That was in Kootenay Pass. Traditionally, the Kootenay Pass program was a very active avalanche program. They had five or six Avalaunchers. Anyone that’s used an Avalauncher knows it’s not the most accurate system. You could often see the slow-moving projectile wander through the flight trajectory and hopefully it would detonate on impact. Sometimes, because of a soft snowpack, the primer wouldn’t get impacted by the striker hard enough and you’d get high dud rates.

I remember getting a call from John Tweedy one night, late in the evening. The phone rings and it’s and he was telling me, “Well, we just had a huge cycle in Kootenay Pass and every time I try to shoot that Avalauncher, it either wanders off-target or doesn’t detonate.” He was saying, “Get me a gun that shoots straight.”

So, I got him a gun that shoots straight. We got him a recoilless rifle. We had a recoilless rifle program for quite a while, but anyone that’s shot a recoilless rifle knows that not only the sound of the gun going off, but the pressure wave it creates is pretty severe. It’s like getting someone to stomp on your chest with the pressure change. I had a fellow come in from Toronto and do a decibel check—it was 183 decibels beside the gun, which is off the scale. So, we had a couple of years of a recoilless rifle program. It was a straight-shooting gun, but the fragment dispersal pattern from that was also very severe and there was an unacceptably high dud rate for that as well.

That’s when we got the Gazex cannons. Gord Bondwick was a big part of getting that program together. That was one of the early installations of Gazex in B.C. It has grown to the point now where, gosh—it’s been a while since I’ve been involved with the program—but it seemed that every summer or two after that there was, “Oh, let’s put another cannon here, another one here.” So, it just kept growing and expanding.

That has worked out really well for the Kootenay Pass program. They’ve shortened their closure times and have far more reliable control. I bought John Tweedy a red flannel housecoat and got some yellow fluorescent markers on it, and I said, “Here’s your new avalanche control jacket.” You can put on your house coat and slippers and have a cup of hot chocolate and do control off your laptop in in in the shack now.

The other remote avalanche control device that the program eventually got was an Avalanche Guard in the lower avalanche path just east of Revelstoke. It was after an event that occurred where a large avalanche affected the highway just in front of the snow shed there, and a truck drove into it and caused all kinds of grief. So, I got support to develop an Avalanche Guard program there, and that’s been really successful as well.

Of course, just as I was leaving the program, there’s the remote-control system at Three Valley Gap. That’s been great. That was certainly a push that I was working on in the later stages of my involvement in the ministry program, is let’s promote remote control systems as much as possible. Yes, huge capital costs, but in the long run, well worth it. It keeps our avalanche staff safer, far more reliable, and you just have the cost of maintenance once you incur that capital cost. It’s great to see that the program is developing more and more remote-control systems.

I’ve lived in Revelstoke long enough to know that the length of avalanche closures has decreased drastically since the Wyssen Towers were installed in Three Valley Gap. And the work in Rogers Pass has made a huge difference.

Well, you know, there’s a confusion, I believe, by the general public and certainly the media. When Rogers Pass was closed, a lot of folks didn’t seem to realize that that was a federal program. That’s not a provincial program. I would get calls from media—I took a lot of media calls during closures, of course—and I would quite frequently get calls when Rogers Pass would be closed and media asking why is the road closed, how long is it going to be closed? Not my problem. I’ve got eight other programs to deal with.

Just curious, you mentioned Gazex. Was that the first in B.C? Were they using that somewhere else before you installed one IN Kootenay Pass?

Oh boy! You’re testing my memory now. Was there one at Sunshine Ski Resort? I’m not sure. I have no idea, sorry.

I’m just curious.

My follow up is: where did you hear about the Gazex systems, or how familiar were you with them?

I can say they were developed in Europe. I would always go to the International Snow Science Workshops since the one after Whistler ‘88. I would attend those every two years. There were always presentations about these remote-control systems at the time, but they’re primarily being deployed in European countries. That’s, I suppose, where everyone first heard about these sorts of systems.

Just given the severity of the avalanche risk, Kootenay Pass seemed like an obvious choice to get the first one there.

Oh no, wait a sec!

We also had Gazex program at Duffy Lake at Path 51, I think they called it. that was a large avalanche path that could affect the Duffy Lake Road. Our first one went in there.

Pardon me. So Scotty, if you’re listening, you were the first one. There you go.

Was it difficult to convince the higher-ups to spend that money?

Damn right it was! The pursuit for capital dollars is, is rather intense. You’re competing with all kinds of other programs and highway construction, and there’s only so many dollars available. When the avalanche manager comes along and says, “I really need something like this,” you really have to have a strong business case and justify the expense before anyone’s going to sign over the dollars.

I’m sure the same thing when Jack was working on the program or Geoff Freer before him, that trying to secure funds for projects like that, it’s a tough sell.

With the initial Gazex, you weren’t managing the whole program, it was still Jack, but were you involved with making that case and trying to figure out where to put them?

I would leave that to more of the executive level. That was a pay grade above me at the time that’s for sure.

It’s great to see nowadays. In some respects, I start to wonder, especially with the kind of winter we’re having now, is this going to be the trend for winters to come? That we finally get to the point where we have all these remote control systems and are we going to be facing the future with diminished snowpacks and reduced avalanche activity. if the snowpack at the lower, mid elevations is going to be so much reduced? I hope it’s still money worth spending.

I can’t think of any avalanche control operation in Three Valley Gap this winter (2023-24). There’s only been one significant storm in Revelstoke.

I remember the chief engineer at the time, Dirk Nyland, would be telling me, “Mike, if you’re going to design or develop programs for the future, you have to consider climate change. Don’t rely on historical data because that’s over now.”

This was our chief engineer for the province advising all of us in the avalanche group at the time, before he retired recently, that you have to anticipate what your statistics may be for weather and snowpack depths and all that in the future, which is really hard. How can you do that? Because up until then, you would rely on your historical data to determine how best to manage the avalanche risk for the future. What do you do when your historical data no longer applies to future conditions?

And you don’t have quite the robust climate models that they have now. I guess those have come a long way in the last decade, but, 20 years ago, those didn’t exist.

Well, something for us all to think about, I guess.

The last thing I want to ask you about was, after the Boulder Mountain avalanche in 2010, you launched a program to get billboards up along the highway with avalanche safety information. What inspired you to spearhead that project?

It’s just I was trying to get the message out to snowmobilers that there is a source for getting information that would ensure your safety if you’re going out into the backcountry. Before you head out there, check the avalanche bulletin, check the weather forecast, get some ideas on what you can do to ensure your safety. That was the push there.

We identified—I can’t remember how many sites there were—but we created a sign with our provincial sign shop that provided that information on where to get the information. It was a bit challenging because there was a bit hesitation and resistance that it felt like we were preaching to snowmobile groups, and what about everyone else? Why don’t you have a sign for backcountry skiers or snowshoers? We were getting some feedback from some of the snowmobile groups that you’re picking on us, a leave us alone kind of attitude.

But the statistics spoke for themselves. The Boulder avalanche accident and the high frequency of involvements with snowmobilers, and the activity of high-marking, this is high-risk behaviour folks. You really need to pull your horns in if you’re going out there with a big powerful machine. There’s that sense of invincibility, that I’m protected and safe. If you’re going to go out, take a beacon, probe, and shovel, get some training, and check the bulletin before you go out. That was in essence the message those signs were trying to deliver.

Great.

Before I get to our last couple of questions. You left the avalanche program in 2016, but you’re still with the Ministry of Transportation. What’s your role now?

I’m doing something I never thought I would do. I project manage for rehabilitation and capital construction projects now, and oversee rehabilitation of bridges doing seismic retrofits and things like that. It’s been a steep learning curve working on programs like that, but in essence, preparing tender packages for big highway construction projects now. It’s challenging work, but very rewarding and I actually quite enjoy it now. It was a bit tough when I first started it, but it was a good career move at the time.

Why did you make that move out of the avalanche industry and into other projects?

Well, it wasn’t so much my decision. It was something that had been offered and one of those things that we’re offering you a new position, so we expect you to take it. It was, “OK, I’ll happily accept and move on.”

Are you still involved with anything avalanche related?

No, I’m afraid not. I went to the CAA annual general meeting last year and I’ve been to one before that, but no. I’d like to continue at least going to the AGMs. I’ve always found them very stimulating. The presentations are superb. The continuing practice presentations are always interesting. I ran one of them one year on explosive programs. There isn’t so much just going there for the technical reasons, there’s all the social reasons of course. I think anyone that goes, it’s just great to meet up with your colleagues. I go for a bike ride—I’m an active cyclist. It was always an opportunity to meet up with folks that that you work in the same business and have an opportunity to catch up personally and have a beer or two and go for a bike ride. I’d like to think I’ll continue to go to the AGMs.

Great.

Before I get to our last two questions, is there anything about your career or your work with the CAA that I didn’t ask you about it?

No, I think you’ve covered it pretty thoroughly I’d say.

Thanks.

So, the last two questions are ones we’re asking everybody we interview. The first is: what do you think is the biggest accomplishment of the CAA over its 40-plus years of existence?

I think promoting and establishing a true professional presence of avalanche workers. In the early days it was just folks just learning either on their own or from someone else. Now it’s a recognized profession and I think that’s real accomplishment that the CAA has helped to achieve that. People take real pride in holding a card that says you’re a professional avalanche member and I have these competencies and abilities, and I’m proud of it.

You’re still attending the AGM, so maybe you have some insight, but what do you see as the biggest challenges the CAA or our industry might face going forward?

Oh gosh, yes. Like I say, I’ve been out of the industry for a while, but just carry on doing the good work. Don’t sit back on your laurels. Don’t stop pursuing excellence. Try to attract the best possible folks on the committees, on the Board of Directors. I really think they’ve done a good job of that. Like I say, in the early days, it seemed that it was a really tough sell trying to find someone that would even sit on the Board just because people are so busy in their personal and work lives, that you’re going to take this on now. And it’s a volunteer position that actually takes a lot of work and effort. But I think those positions have become somewhat sought after now, so rather than trying to convince people now, you’ve got people going, “Yeah, I’ll take that on.”

I think that’s a real achievement that the Association has done. And just carry on doing the good work that that they’ve been doing for years.

Well, that’s it. Thanks so much, Mike, for your time.

I enjoyed this.

I hope I see you at a future Spring Conference so we can meet in person.

I Look forward to seeing you at the spring conference. Bring a bike.

I always do.