By Tim Haggerty

This article originally appeared in The Avalanche Journal, Volume 127, Summer 2021

INTRO

In the 2019-20 winter, Whistler Mountain experienced a 1-in-10-year weak layer that persisted in-bounds for six weeks in December and January. This article looks at how the snow safety team handled this PWL and the management plan the forecasters put in place to deal with the uncertainty surrounding it. It looks at our AM and PM workflows and how we have developed them to encompass debiasing strategies, reassessment, and reflection on an on-going basis. Lastly, we will cover how we communicated our concerns to management, our workers and our guests.

CONTEXT

Whistler Mountain makes up one half of Whistler Blackcomb (WB). Each mountain has separate patrol and avalanche programs, the main reason being the mountains’ separate histories. Whistler opened in 1966 and Blackcomb in 1981, and they operated under separate owners until 1997. The second reason is the nature of the terrain on each mountain.

WB is located in the south part of the Coast Mountains in a transitional zone between coastal rainforest and the drier climate of the Cariboo-Chilcotin. It primarily has a maritime snowpack, but does receive continental influences such as Arctic outbreaks and extended dry spells. We operate 23 lifts that service all elevation bands, topping out at 2,180m. Our terrain atlas contains over 200 slide paths that can produce size two or greater avalanches, as well as many more micro features and terrain traps within our operating boundary.

UNIQUE CHALLENGES

WB has a long operating season with alpine lifts usually planned to open the first week of December and staying open until the end of May. Due to the size of our acreage and the guest volume, our operation runs 24 hours and various departments require access through avalanche terrain at all hours to prepare the slopes and lifts.

On Whistler we have up to 6.5km of cornices. Broad ridgelines and lee-facing bowls are accessed by all alpine lifts. Green and blue groomed ski slopes run parallel to the cornices, providing guests with easy access to nature’s elevator.

ELEMENTS AT RISK

Elements at risk to avalanche hazard on Whistler include workers, guests, structures, and our reputation. Workers consist of two categories:

- Avalanche workers: Patrollers with a minimum of CAA Level 1 certification who are involved with direct short-term hazard mitigation. They require further in-house training and personal protective equipment (beacon, shovel, probe, and airbag pack, all issued by WB).

- Non-avalanche workers: These employees are allowed on designated routes through avalanche terrain and require the avalanche forecaster’s permission to travel.

We control guest exposure by closing lifts that access the terrain when the existing avalanche hazard is greater than size one, while also closing avalanche signage and placing guards to keep uphill travellers out of our danger areas. Cornices are dealt with on an ongoing basis with explosives work. In addition, our grooming team pushes 1m vertical berms at the approach to some of these large cornices to deter people from approaching them.

We limit risk to the few lifts that are exposed to avalanche hazard with earthen deflector structures that decrease their vulnerability. We send teams out during large storms to perform control work to mitigate the avalanche destructive potential of these slide paths, reducing the impact pressures to the towers in the event they are hit, and decreasing the run out potential of any avalanches.

THE WINTER OF 2019-20

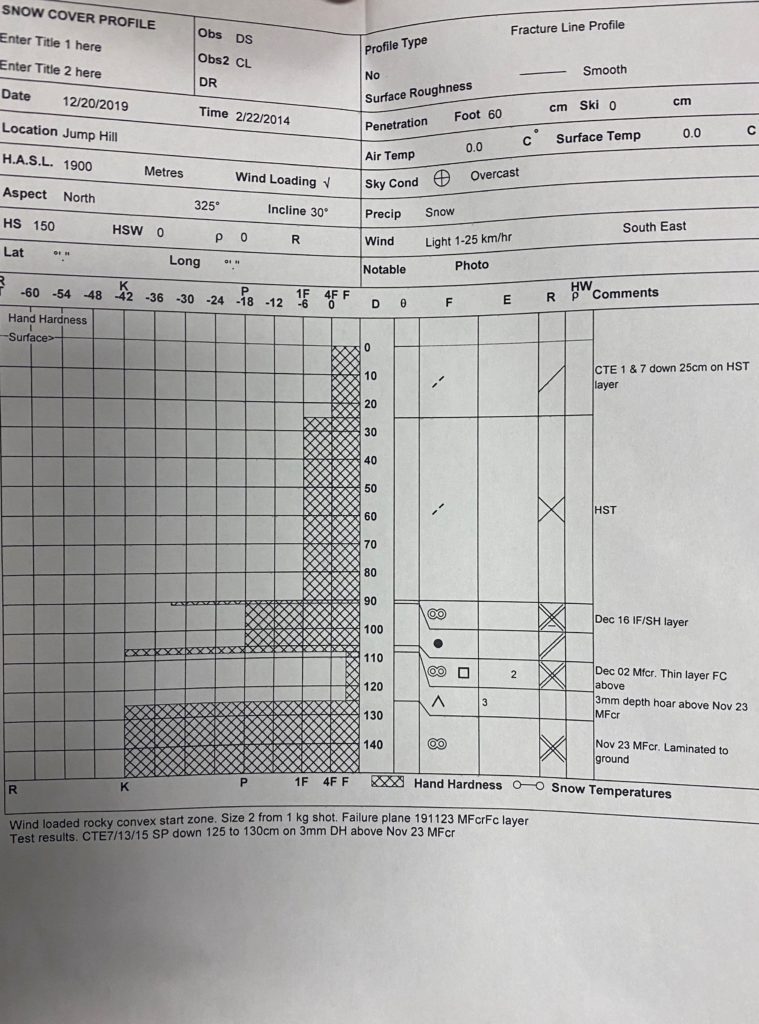

This was a below average season with 948cm total snowfall. The early season was warm but we managed to open on November 28—two weeks later than normal—with a snow depth of only 28cm at 1,650m. An Arctic outbreak in late November contributed to weakening the shallow snowpack and small amounts of incremental loading through mid-December had us pondering when the tipping point was going to arrive. We observed the first remote activity on this layer on Dec. 7, with the first large cycle on Dec. 21 and 22.

A near-record January brought 478cm of snow and 27 days of avalanche mitigation work along with it. The avalanche hazard rose to high or extreme for eight days during the beginning of the month, with multiple large natural and controlled avalanche cycles. The Peak Chair did not open until Jan. 14 due to the active PWL, one of the latest openings on record. The times we were able to open the high alpine lifts were brief lulls in the PWL activity and we were only opening in small spatial steps.

Finally, a warm, wet atmospheric river arrived at the end of January, dropping 108mm of precipitation in 36 hours, with 70mm of that falling as rain to 2,000m. This flushed out or bridged over our early-season snowpack weaknesses and the PWL went dormant.

February and March were cold, with light but consistent amounts of snow. The skiing was good and the stress and fatigue from the season were put to the back of our minds. We closed March 14 due to the global pandemic.

MANAGING UNCERTAINTY

Managing the uncertainty surrounding this PWL made us collaborate on a plan with Blackcomb and our other neighbours. This involved continually gathering evidence, timelines, and slope tracking, while operating with large safety margins to minimize or eliminate the exposure to staff and guests.

When gathering evidence, we relied on the strength of outlier events and weighted heavily the snow profile data that we were collecting daily. Even when there was a lack of direct evidence, we knew the facet/crust layer was lingering and it made us question the stability of the slopes we tested. This is what we deemed the “Rockies Mindset.” We were trusting the “base rate” or, in other words, the terrain. If a path had snow on it in early December and could produce an avalanche, it was tested with explosives. Then it was re-tested whenever any new stress was added.

As for time considerations, we added an explicit 24 hour rule: after any significant result occurred or any new stress was added to the snowpack, every large slope was tested multiple times over several 24 hour periods. We used a helicopter to reduce exposure to avalanche workers on the ground and to place bigger charges of either 4 kg of Emulex or 12.5 kg ANFO bags. Time also allowed the snowpack to set up between mitigation efforts. A couple of cycles in January took four to five days of this routine before we could confidently open the terrain.

We tracked all slopes that released on InfoEx using the photo overlay extension and the freeform in the PWL assessment to write in slopes and dates when they released. We started ski packing our shallow easterly tree line terrain to break up the facet/crust layer—this is not a normal mitigation technique on the coast.

Large safety margins were implemented through the use of helicopter deployment and by limiting exposure to avalanche workers by restricting their travel in all alpine bowls. We used larger explosive charges in various trigger points to test all of our large alpine start zones. Alpine terrain remained closed for long periods of time during December and January.

DEBIASING, REFLECTION AND WORKFLOWS

Over the past couple of seasons our snow safety team has implemented debiasing strategies through our InfoEx workflows. With such a large team, coupled with the perceived and personal pressures, we are likely to be biased in our hazard and risk assessments. To combat this, we need to recognize what are assumptions and what are facts. This helps to understand if our uncertainties fall outside of our risk tolerance and directs us to question what is acceptable for the given avalanche problem.

In our AM workflow we ask ourselves:

- Do the avalanche problems reflect the hazard rating?

- Is our operational plan on par with our strategic mindset?

This puts reassessment into our morning discussion and hopes to add a rational discussion based on data and evidence as well as pattern recognition. This discussion takes place between the forecaster and the snow safety technician of the day to promote team decision making. We ask: ”Is our intuition steering us wrong with our plan or our mindset?”

Reflection is done with any consequential decision, whether the outcome was good or bad. This helps us recognize patterns, which eventually leads to us being able to make better intuitive decisions in a fast-paced environment.

Our PM workflow discussion is built upon the CAA Level 2 PM form, but is tailored to our program’s needs. It asks:

- Were there any inconsistencies from the AM hazard and what were they? This catches trends and personal biases.

- Were there any contributing human behaviors? This includes the forecasting team, management, workers, and guests. We include all pressures, near-misses, and influences on the program.

- Was our operational plan appropriate? Were we operating within our operational risk band or were we too risky/conservative? Did we think how our decisions would affect the operation as a whole?

We stress debiasing and reflection in our snow safety program so that our team recognizes we are all fallible. Our goal is that honesty and humility will create a safer patrol culture through sharing our own mistakes.

COMMUNICATION

Communicating our concerns for this 1-in-10-year PWL was the hardest part. We were quick to remind management of the 2008-09 season, when two lives were lost in two days in terrain outside our operating boundary.

Our forecasters were able to recognize the severity of this PWL early in December. We were able to talk to upper management on a daily basis, providing strong and consistent evidence that we would not be able to open high alpine lifts safely by mid-December and that this layer could plague us into January. We laid out our plan and provided a cost/benefit analysis for working terrain hard versus just waiting for the snowpack to heal. We worked it hard on Whistler Mountain. At no time did our senior leadership team pressure us to open terrain or lifts.

During daily meetings with our patrol we described our uncertainty in spatial variability and the likelihood of triggering. We emphasized team decision making in the field and constantly discussed previous seasons’ PWLs with route leaders in front of the group. We consistently communicated our large safety margins and reassured teams to slow down and that there was no operational pressure to open the terrain. With debiasing and reflection built into our workflows, we discussed these as a group in the AM briefing before avalanche control commenced.

A “Rockies Mindset” was encouraged and explained to the patrol and non-avalanche workers in regard to conservative decision making, terrain selection, and patience.

Communicating this to our guests was a different story. With such a dismal start to the season, the public was chomping at the bit. When the snow arrived, their coastal mindset of “If the ground is covered in snow it’s good to go,” kicked in. Poaching avalanche closures became a regular nuisance and a lack of natural activity and visibility was our worst enemy as the terrain remained closed. Skier accidentals and skier remotes were all too common in the closed terrain.

Our normal avalanche sign lines needed to be beefed up, often with guards or by closing buffer terrain. New for this season was our uphill travel policy, which was developed to help control guests with touring gear from hiking inside our boundary. This limited guests to certain routes that were signed and open or closed based on lift access and avalanche closures. Once the public adjusted to the new written policy it was easier to communicate our concerns.

Avalanche Canada seemed to be on speed dial during the PWL cycles. We were able to provide them with strength and weight of evidence, as well as express our uncertainty in how long this PWL was going to remain reactive. This was our only public outlet; our company’s media policy keeps our staff from being able to communicate on social media or through the news. Avalanche Canada did a great job of relaying our concerns with the persistence and the consequence of this layer. There were a few near-misses in the backcountry, but no one died in the Sea-to-Sky from this layer.

SUMMARY

This PWL remained active for six weeks resulting in our high alpine lifts opening two to four weeks behind schedule. We conducted avalanche control with explosives 46 out of 76 days, with our season ending on March 14.

There was a lot of learning during the 2019-20 season:

- Dealing with uncertainty and accepting patience as a tool to decrease it. By creating time in the morning workflow and by having a pre-plan with a few explicit rules, we were able to decrease pressure on the team by communicating these ideas.

- Training. When we were not doing avalanche control, we trained. This included AvSAR response, companion rescue, and route training. This helped patrollers be more efficient and effective with their decisions and actions in the field while under stress.

- Debiasing and reflection should be in everyone’s workflows, professional and recreational. Be humble and honest with yourself and your team whether the outcome was good or bad.

Our forecasting team believes that running a safe, effective and efficient snow safety program is not just about snow science, but how we manage people in our terrain. Our program is extremely complex. By focusing on human behaviour, reflecting on our actions and decisions, and effectively communicating our concerns, we hope to be able to push for a safer mountain culture.