ON CHRISTMAS DAY 1996, a young ski patroller at Big Sky, Montana, lost her life following an explosives accident while conducting avalanche control. The tragedy had repercussions across the North American avalanche world when explosives companies refused to supply industry in the aftermath. In Canada, the situation was looking dire when CIL Explosives stepped in to fill the void.

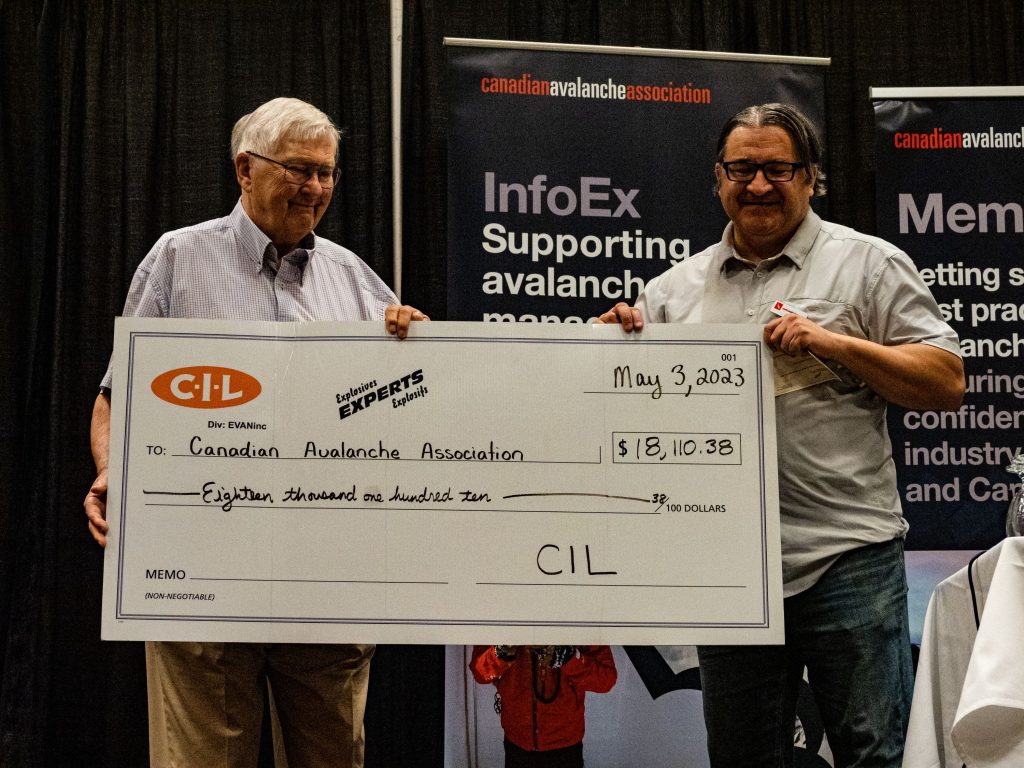

Last year, Everett Clausen, the owner of CIL, sold the company to Austin Powder, marking the end of a nearly 30-year-long relationship with the avalanche industry. CIL Avalanche Control continues to serve the industry as a division of Austin Powder, led by Braden Schmidt, but

Everett is now retired. We spoke to him a few weeks before the Spring Conference about his long relationship with the Canadian avalanche industry. This is an edited transcript of this interview. Check out the video for the full interview.

Alex Cooper: Maybe we can just start with a bit of background on your own history in explosives and CIL’s background.

Everett Clausen: CIL is a company that’s been around for 150 years. It was always in the general explosives business. I joined them after I graduated from university and worked in their ammunition and explosives division. Then, at some point, myself and Andre Gagnon purchased what I will call the pyrotechnics part of that division.

One of the first things that happened was that in the U.S., there was a very unfortunate and terrible accident where two avalanche practitioners made an error using a primed explosive and held on to it too long. One of them was killed and I think the other was seriously injured. Following that accident, the manufacturers of the explosives, who at that time was Ensign-Bickford, paid out a $4 million court challenge and decided they would never again sell explosives to the avalanche business. That made it very difficult, particularly in Canada, where there was so much avalanche work being done in B.C. and Alberta in road clearing and wintertime travel.

The Canadian government, through the explosives division, contacted me to see if we would have any interest in supplying. We did a very in-depth survey of Canadian operations. We were satisfied the folks who were using the explosives were doing so in a safe manner, and also that B.C. had a very good training program, so we decided, yes, we would get involved. That’s what led to years and years of very successful cooperation and client-supplier relationships.

What were your products or specialties before getting involved in the avalanche industry?

Before that, we were primarily involved in pyrotechnic flares—that would be marine flares, the flares that you see carried on boats in case there’s an emergency. These would be parachute flares, handheld flares, orange floating smoke, things of that nature. We also did do quite a bit of supplying general contractors, such as beaver dam people who were using explosives to open up rivers. We supplied them with the detonating cord and some nitroglycerine-type explosives.

What did you know about the avalanche industry when you were approached to start supplying it?

Very little at that time. It was a steep learning curve for us as we looked into how well people were trained, the incidents that had been recorded. Talking to different potential users and finding out that certainly in Canada, the people were well trained and well versed in the use of those explosives. It was a fairly easy decision for us to agree to develop the products needed and be the sole supplier.

What did you have to do as a company to begin supplying the explosives and fuses?

What we did do initially is deepen our relationship with a large explosives company in the U.S., that’s Austin Powder, who had plants in central U.S, South America, and Europe. We developed with them the necessary explosives to be used in general avalanche use. At the same time, we deepened our relationship with a company called Omni out of Arkansas, who were assembling fuses. What we did then was to search out the best supply of fuses and the best supply of blasting caps that we could find. They came out of Bolivia. Omni has an assembly plant in Crawfordsville, Arizona. They supplied us with the product we called Mildets, because the fuse actually was a military-type fuse, a

green fuse—high quality—that passed all the military specifications that were set out and has proven to be a highly successful and a very reliable product.

So, you basically had to put these together and then create the explosives they would throw out of helicopters or chuck while on a ski patrol control route?

That’s right.

What were some of the major challenges you faced in those early years?

Well, I wouldn’t call it a challenge, but one of the things we had to do was to make sure all of our products had been tested and authorized by the Canadian government. Then, when we looked at people in the U.S. wanting to do it, we had to do the same thing down there. Go to the department of transport, make sure it had an EX number, make sure it had been all tested. Those things are not difficult, but they keep you busy. Once that was all approved, the customers really came to us. We had very little selling to do.

How long did you have to get all this going? I understand it must have been a fairly quick transition because of all the uncertainty.

Yes, it was probably no more than a couple of months.

Wow.

Which is really fast for developing that kind of business.

That seems like something like that should take a few years normally. Was there pressure or support from the government to get this going because of the importance of doing this work?

Oh yeah, no question. They were the ones that were really pushing it because you can imagine, winter comes and there’s no way to clear the roads in B.C. and Alberta. That was a real worry for them, so they worked very hard with us to get everything done properly and quickly.

What was your relationship like with the CAA at this time?

At that time, we got involved because the people who had helped us a lot from the practitioners’ point of view were members of the CAA, so they brought us in. We quickly developed that relationship with Clair Israelson and other folks, and became a big part of the CAA to the point where we supported them a lot, and supported training by virtue of setting up a plan where we would pay people 3% of our sales

in order for them to be able to do training.

And how did that come about?

I have to say it was part of a marketing plan as well. If people are going to get 3% of their sales back in terms of a dollar value, that interests them, and it also interested us because it meant that they agreed to take that 3% and use it to train all of their practitioners. It was a win-win situation.

When did you start attending the Spring Conference?

Very shortly after we got into the business. It gave us an opportunity to expose people in the CAA to the operational side of the explosives part. I enjoyed that very much. Those were a lot of interesting years where we were able to do that and allowed to talk for an hour or so at a time to people at the CAA.

What are some of the big changes you’ve seen in avalanche control explosives over the last three decades? I found one article in our archives where you helped with the development of the first Avalanche Guard system near Revelstoke. I’m thinking of that, but I’m sure there’s a lot more. I wonder if you could just talk a little bit about some of those developments over the years.

I think the use of remote ignition systems was a very important development because before that, when we first started, initiation was by just tossing 3” x 16” nitroglycerine sticks into the valley. There were some remote ignitions, but these were mainly done by artillery guns. Very important developments came with these specialized Avalanche Guards, and with the Nitro Express systems that could be moved, aimed, and deliver explosives from kilometres away. To me, that certainly was the most important development I had seen in the years I’d

been there.

What was CIL’s role in in developing those?

We developed a gun, along with training people. That was that was a good part of the job that Braden Schmidt did for us for a number of years. He’s now the President of CIL Austin Explosives, but he did all that development for us in the last eight or nine years. We were deeply involved in in that gun development.

Just to clarify, when you say “that gun,” what gun are you referring to? I’m not an avalanche control guy myself, so I don’t know all the ins and outs, but maybe you can just elaborate there?

It’s called the Nitro Express and it’s got a long barrel, 15–18 feet, and it projects a four-pound booster charge using nitrogen gas. It propels it by that gas being confined and driving the booster out and up to four kilometres. That’s an interesting development, and it means you can aim and direct. If you look at our website, which you may do after, you’ll see how that works. There’s a video there that shows you (note, the video is not currently available).

So, we talked about the Spring Conference, but you’ve been a fixture there for a long time. I’m wondering, how your relationship with the avalanche industry compares to other sectors you work with?

I would say the avalanche business, CIL and myself personally, have a closeness I didn’t have with the other parts of our business. You know, we sell highway flares to all of the police forces. It’s good business and we work with them, but certainly not with the kind of closeness we have with the avalanche business. And I know that Braden is carrying that on.

What do you think you’ll miss about this industry and this work?

It’s an interesting business and the people who are in it are—I’m not going to say quite strange—but they’re quite different. There’s a wide range of people, all the practitioners you meet. There’s a broad range of personalities and that’s something I always enjoyed because you never knew quite what to expect and that’s always nice when you’re running a business.

Well, thank you so much, Everett. I appreciate your time. We appreciate the support over the last 30 years and congratulations on your retirement. It’s well deserved.

Thank you so much. I’ve enjoyed every minute. Not retirement, but all the days working.