AS I ASCENDED THE SLOPE, the gut dropping whumpfs reverberated through the soles of my feet. Kinetic energy was converted to electrical impulses, shooting straight to the stress centre in my brain. My amygdala lit up, and instantly every part of my body screamed to run away.

I casually expressed concern to our team leader. My body pulsed with fear and stress, but my mind and ego contained my physiological dread. I was an avalanche worker after all, sent to investigate an avalanche problem. As a team, we had discussed this problem, chose terrain to minimize exposure, and made a plan to ensure our risk margins were acceptable. As we climbed closer to our profile site, the unease grew. I wanted to get out of there, but I said very little. I took pride in getting the job done and did not want to disappoint my team.

As an avalanche survivor, the feeling when the slab broke above me instantly carried me back to that powerless moment 10 years ago when I was almost killed. Again, I was carried down the mountain, skins on and helpless, knowing that with enough momentum I would be taken off the ridge and into the main path. It could be over, but it wasn’t. Our terrain choices and risk assessment saved us. It was a near-miss—a size one—and nothing bad happened. Yet I felt guilt and shame, a deep unease with the separation of mind and body. I wanted to say no, but lacked the ability to express my concerns.

Digging into my workplace near-misses over the last decade, thankful that they were just that, I noticed this theme persisted. As avalanche workers, we spend much of our time dealing with avalanche problems. We expose ourselves to keep others safe, and when we are given objectives, we take pride in our ability to achieve them. While avoiding incidents is always a priority, downplaying our physiological red flags, environmental clues, and surrendering to task saturation is easy in the field. Often, when given an objective in the office, the story is only the beginning; as workers, we strive to bring it to completion. New information that changes this story, especially if it causes complications, can be intimidating. It is hard to say “no.” Fear of reprimand, of loss of respect, or the martyr-like complex of “someone has to do this so it should be me,” can be easy lures into the trap of an avalanche accident.

LEADERS VS FOLLOWERS

As I read through case studies and books dedicated to big accidents, it became clear many of them stemmed from discord between the leader and the follower, but the focus of the reports was on leadership errors. This came as no surprise. The importance of leadership and the skills that make a good leader are taught in many levels of education on the journey to becoming an avalanche professional. However, little to no education addresses our role as followers.

As a society, we often admire and respect our leaders, whereas followers are cast in a negative light. Descriptors such as lackey, underling, henchmen, or minion are often used. Images of cultists and mobs often accompany the idea of the follower. We ignore the reality that followers greatly outmatch leaders in numbers. Many of us will spend far more time in follower roles as opposed to leadership roles, yet followership takes a backseat to leadership.

This perplexing dichotomy between leader and follower sells the follower short. A leader is nothing without followers, and in our industry, a good follower can be the keystone to preventing avalanche incidents. In addition, a good leader must know how to follow and when they should take on a follower role. External organizational pressure is exerted on most leaders, and adopting the follower mindset with a simple goal can have great value. Rigid hierarchy can often stifle followers and isolate leaders. In a cohesive team, a follower with specific experience or expertise can step forward and then step back when needed.

Where there are many potential objectives, such as delivering a guest experience, protecting workers and the public, or opening terrain, our goals as workers remain static:

- to avoid involvement in an avalanche large enough to injure or kill you; and

- to avoid unnecessary injury or incident from the many other hazards in the mountain environment.

In the mountains, the leader of a group has many things to focus on: weather, group dynamics, the daily objective, communication, decisions, and responsibilities. Meanwhile, the follower has a great advantage—a lower cognitive load, which can be dedicated to the goal.

TYPES OF FOLLOWERS

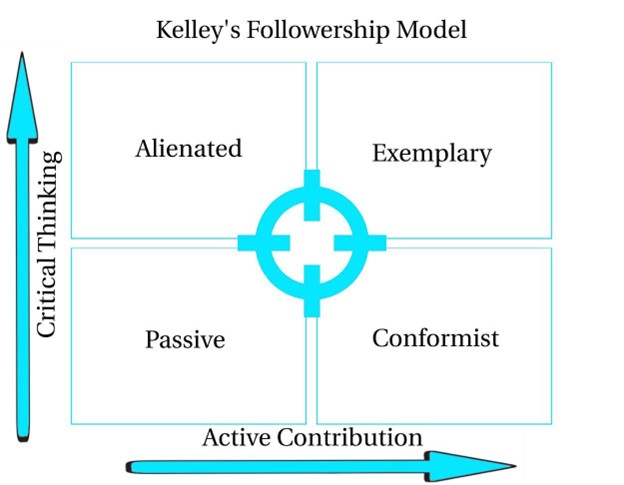

What makes a good follower? Kelley’s followership model (Fig. 1) breaks followers into four main categories (alienated, exemplary, passive, and conformist), with two key variables (critical thinking and active contribution). For Kelley, the finest follower is a critical thinking contributor who does not simply acquiesce to their leader, but instead plays the role of contrarian if needed. This “exemplary” follower is happy to challenge the leader if the goal is being compromised, but if they are in an environment where such behaviour is not encouraged or has negative impacts, they will not speak up, and instead become passive and/or alienated. A critical thinking follower who is alienated is far more likely to be a negative team member.

Often when negative examples of followers are cited, passive and conformist followers are the prime examples. While both of these follower-types are easier to lead due to their compliance, it places all the decision-making on the observations of the leader. It is interesting to note that during a survey by Kelley, the conformists, often called “yes people,” were most desired by CEOs and leaders.

Conformists do what they are told and do not object. In emergency situations, conformist followers are essential. Under stress, we rely on our fast processing power of intuition, what Kahneman calls “system one”. This system is free of critical thought. In stressful situations, often the first thing to be lost is our upper level cognition, we disassociate and run on our intuitive systems. It is why we train and embed algorithms into our minds. The slower processing but more astute “system two” is essential for fine-tuning these intuitions. The more time spent as an exemplary follower, the better we can be when a stressful situation calls on us to become conformist.

ENCOURAGING STRONG FOLLOWERS

As followers, the crosshairs often wander. In a stressful environment, we can execute tasks intuitively without thinking (conformist), we can become defensive, stop contributing and shut down our critical thinking skills (passive), or silently criticize the leadership without objection in the moment (alienated). Followers in these states can be victims in an avalanche incident. Without participation and active critical thought, followers play no part in the decision-making process and in doing so, take no responsibility. In the mountain environment, with minimal feedback, one member of a team could be receiving several signs of instability, whereas the leader could be blissfully unaware of the

potential for an incident.

Workplaces are often environments of rigid hierarchy. Senior staff have often gained the experience and skills to lead effectively over time. As an industry we also value algorithmic thought, which can help prioritize and triage tasks, but leaves little time for critical thinking. While these elements are essential, making room for exemplary followership can help increase safety margins. Often it is difficult for followers to speak up due to hierarchy, fear of reprimand, or a work environment that does not encourage critical thinking and active contribution. Furthermore, our collective obsession with leadership means the coveted role of leader can be something sought after, not to be given away. Instead of fostering teams of strong followers, we often focus on our leaders. If an incident occurs, the leader is to blame when many individuals were involved to reach that outcome.

How as an industry, do we value and teach followers to keep us safer in the mountain environment? With its myriad of uncontrolled factors, guaranteed safety is impossible, but we can increase our margins. While we cannot control the mountain environment, we can create a workplace environment that encourages open communication by allowing all team members to speak up when they feel uncomfortable. The workplace must be one that puts the goal above objectives and makes every team member feel valued and heard. Everyone should be encouraged to contribute and think critically.

We should recognize that under stress, it is difficult to think critically; making efforts to decrease stressors in the workplace are all good steps. Most importantly, the follower role should be valued. A follower is not below the leader but rather a separate, integral part of a team. While seniority, experience, and familiarity are all important tools, they can be heuristic traps in their own right. Having a varied team all contributing, all thinking critically to increase safety margins, can greatly help the odds of avoiding accidents in avalanche terrain.

REFERENCES

Baker, S. D. (2007). Followership: The theoretical foundation of a contemporary construct. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 14(1), 50-60.

Bass, B. M. (1990). From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organizational dynamics, 18(3), 19-31.

Blehm, E. (2024) The Darkest White: A mountain legend and the avalanche that took him. New York: HarperCollins.

Davis, B. S. S. (2022, December). Pro tip: Separate your goal from your objective. Powder Cloud. https://thepowdercloud.com/learn/essential-touring-skills/protip-separate-your-goal-from-your-objective/

Brymer, E., & Gray, T. (2006). Effective leadership: Transformational or transactional?. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 10, 13-19.

De Decker, R., Roos, J., & Tölken, G. (2017). Human factors: Predictors of avoidable wilderness accidents?. South African Medical Journal, 107(8), 669-673.

Daniel, K. (2017). Thinking, fast and slow.

Jamieson, B. and Geldsetzer, T. (1996) Avalanche accidents in Canada: Volume 4, 1984-1996. Revelstoke, B.C: Canadian Avalanche Association.

Jamieson, B., Haegeli, P. and Gauthier, D. (2010) Avalanche accidents in Canada. volume 5, 1996-2007. Revelstoke, BC: Canadian Avalanche Association.

Kelley, R. E. (2008). Rethinking followership. The art of followership: How great followers create great leaders and organizations, 146, 5-15.

Kelley, R. E. (1988). In praise of followers (pp. 142-148). Brighton, MA, USA: Harvard Business Review Case Services.

Kellerman, B. (2007). What every leader needs to know about followers. Harvard business review, 85(12), 84.

Meindl, J. R. (1995). The romance of leadership as a follower-centric theory: A social constructionist approach. The leadership quarterly, 6(3), 329-341.

Riggio, R. E., Chaleff, I., & Lipman-Blumen, J. (Eds.). (2008). The art of followership: How great followers create great leaders and organizations. John Wiley & Sons.

Sapolsky, R. M. (2018). Behave: The biology of humans at our best and worst. Penguin.

Uhl-Bien, M., Riggio, R. E., Lowe, K. B., & Carsten, M. K. (2014). Followership theory: A review and research agenda. The leadership quarterly, 25(1), 83-104.

Van Vugt, Mark. “Evolutionary origins of leadership and followership.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 10.4 (2006): 354-371.

Wylie, K. (2014). Buried. Rocky Mountain Books Ltd.

Zweifel, Benjamin, and Pascal Haegeli. “A qualitative analysis of group formation, leadership and decision making in recreation groups traveling in avalanche terrain.” Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 5 (2014): 17-26.