By Scott Thumlert

This article was originally published in The Avalanche Journal, Vol. 137, Winter 2025

INTRODUCTION

Assessing, rating, and forecasting the physical hazard posed by snow avalanches is fundamental to daily work for avalanche professionals. Avalanche risk mitigation strategies (e.g. explosive control, communicating danger level and terrain advice to public, closing terrain at a resort, selecting terrain when guiding) are implemented largely based on the assessment of the physical avalanche hazard. That is, the

physical hazard posed by avalanches is assessed first, and mitigation strategies typically follow.

There are currently no established Canadian hazard rating systems that include guidelines for how ratings are to be applied and that effectively describe physical avalanche hazard independent of elements at risk. The widely used Conceptual Model of Avalanche Hazard (CMAH) details a framework for data analysis and collection, yet deliberately does not establish a deterministic link from the assessment to operational hazard ratings. According to Statham et al. (2018), “Instead, the CMAH’s model provides the platform for a detailed assessment, and a framework for data analysis and collection. This was done deliberately to support future empirical analyses (e.g., Haegeli et al. 2012; Shandro et al. 2016) in establishing more robust links between assessment methods and any operational rating systems.”

Establishing the link from the assessment framework detailed in the CMAH to operational hazard ratings suitable for professionals is the next logical step.

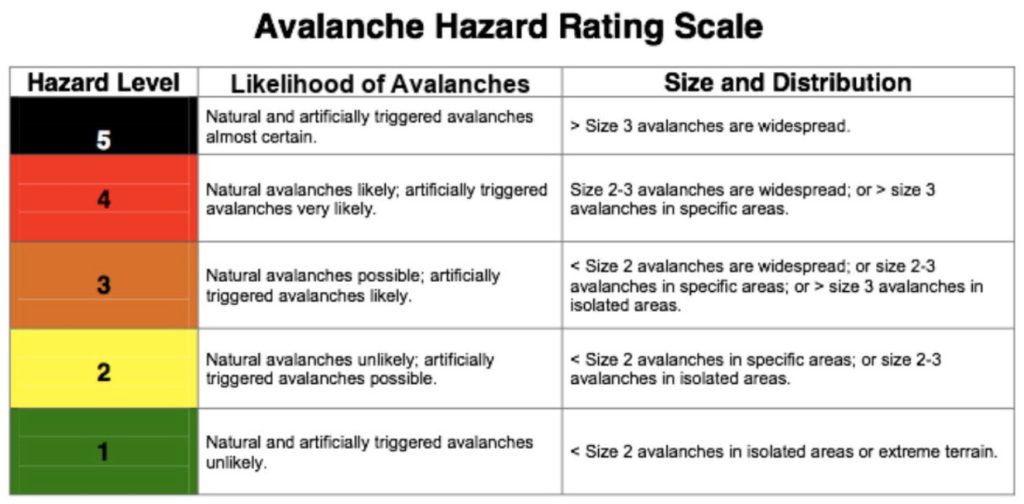

This article further argues the current professional avalanche hazard rating scale used in InfoEx (Fig. 1) is too simplistic to capture the core factors professionals must consider when assessing and rating avalanche hazard. This is likely because it is based on the public avalanche danger scale, which has the primary purpose of communicating avalanche hazard to the recreating public. That is, the element at risk is considered and incorporated into the scale. For example, consider the InfoEx hazard rating scale in Figure 1—it is likely difficult to assign a hazard rating for the following scenarios:

- Storm slab avalanches–likely (naturals)/very likely (artificially triggered) to Size 1.5, expected to exist on all aspects and elevation bands.

- Deep slab avalanches–unlikely to Size 4, thin snowpack areas.

Consider scenario one: the likelihood description indicates the hazard would be high, whereas the size description indicates considerable. When considering scenario two, the likelihood description indicates the hazard should be high, whereas the likelihood description suggests the hazard would be low.

This article provides background on avalanche hazard assessment, details the four core factors contributing to the physical hazard posed by avalanches, and outlines a pathway towards the development of the required hazard assessment and rating system.

BACKGROUND

Avalanche professionals assess avalanche hazard for terrain over varying spatial scales:

- Mountain range or region (e.g. public forecast regions, > 100 km2).

- Mountain or drainage (e.g. ski resort, group of paths affecting transportation corridor, guiding tenure, ~ 10 km2).

- Path or terrain feature (e.g. specific avalanche start zone, < 1 km2).

The variability of the snowpack across larger spatial scales means the physical hazard over terrain also varies. That is, there may be areas of low or no hazard and areas of elevated hazard within the assessment area or forecast region. Avalanche hazard assessment across the terrain in the forecast area must account for this variation.

Modern avalanche hazard assessment systems (e.g. Statham et al., 2018; McClung and Schaerer, 2022) incorporate the concept of avalanche problem types (e.g. dry loose, wet slab, persistent slab) based on Atkins’ (2004) descriptions of the character of expected avalanches. Incorporating the type of avalanche expected provides valuable information about the behaviour of these avalanches, their location in the terrain, and the time this type of avalanche can be expected to exist.

Snowpack assessment can contain a varying number of avalanche problems. In general, early-season snowpacks have fewer expected problems due to the lack of buried persistent weak layers. As the season progresses, snowpacks often get more complex, with multiple buried weak layers, cornice growth, and surface snow instabilities potentially present. An effective assessment of avalanche hazard must include an analysis of how the complexity of multiple avalanche problem types contributes to the overall hazard assessment.

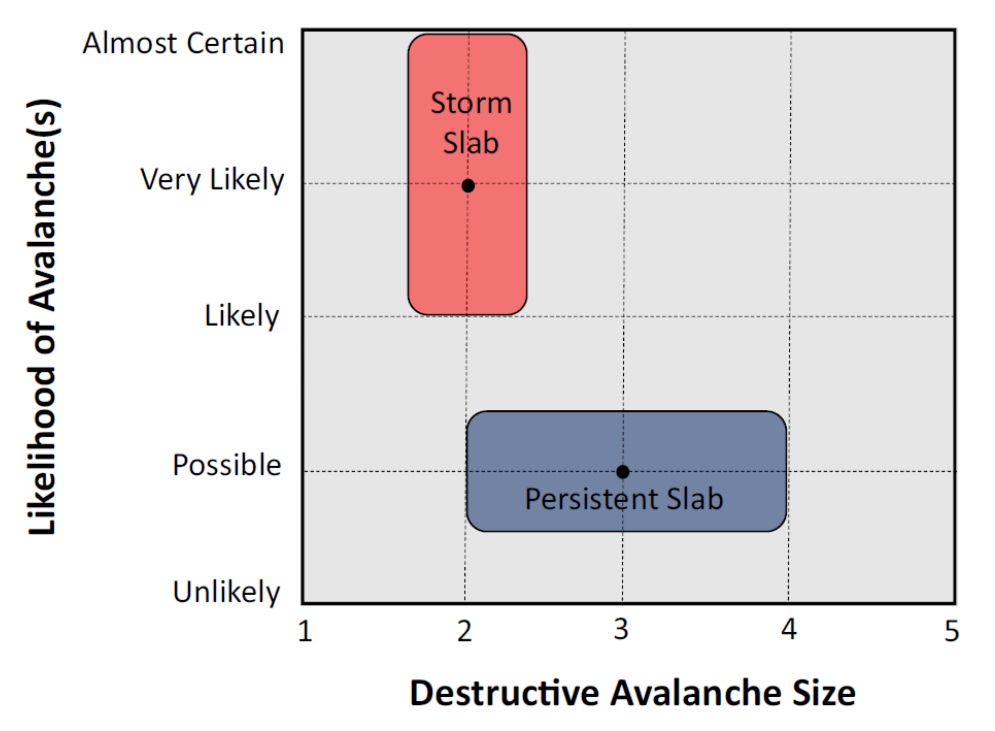

Most traditional and recent avalanche hazard assessment literature (e.g. Meister, 1994; Canadian Avalanche Association, 2016; Statham et al., 2018; McClung and Schaerer, 2022) describes avalanche hazard across terrain as a function of the expected size and likelihood of avalanches. Figure 3 on page 24 shows an example of avalanche hazard with uncertainty illustrated by the extent of the ellipses for two

avalanche problems.

Avalanche size is well described with the Canadian destructive potential scale (McClung and Schaerer, 2022; CAA, 2024), and in general, larger expected avalanches equate to increased hazard.

Assessing the likelihood of avalanches is complex and involves subjective probability assessments (process described well by Vick, 2002) derived from many data sources like recent avalanche activity, snowpack structure, and weather inputs. Subjective probability assessments are now widely communicated with an ordinal scale of verbal probability descriptors: unlikely, possible, likely, very likely, and almost certain (Statham et al., 2018). Higher likelihood assessments should mean more avalanches are expected across terrain.

In general, increasing expected avalanche size or likelihood equates to higher avalanche hazard. However, assessing avalanche hazard across terrain as only a function of likelihood and size is simplistic and does not include the variation of hazard across the forecast region, nor does it allow for the assessment of the complexity of the snowpack by assembling multiple avalanche problems.

PHYSICAL AVALANCHE HAZARD

What components effectively describe the physical hazard due to snow avalanches across terrain? First it is important to define the physical hazard across terrain—a source of potential harm, damage, or loss. Physical hazard can be described as the potential hazard posed by the current or future state of the snowpack. While our knowledge about the state of the snowpack always involves a degree of uncertainty—and more uncertainty can increase risk—the snowpack and the resulting physical hazard does not change based on our knowledge of it. That is to say we can, and in many cases should, describe the potential hazard due to the current snowpack before considering the elements at risk.

Using the concepts presented above, the following four components are proposed to describe the physical avalanche hazard across terrain: likelihood of avalanches, magnitude, amount of terrain, and complexity of the snowpack.

- Likelihood of avalanches: the release probability, historically called snow stability. Likelihood of avalanches is basically the chance of avalanche activity in the forecast area within the forecast time period, or the chance that a specific path or start zone will release during the time period, regardless of avalanche size. Higher likelihood assessments should indicate increased avalanche activity is expected. An effective system used to communicate a forecaster’s likelihood assessment should use clear definitions to promote effective communication (Fischer and Jungermann, 1996), increase forecasting accuracy (e.g. Rapoport et al., 1990), and improve decision-making (Friedman et al., 2018). The likelihood definition and system should also be largely independent of the spatial scale being assessed. That is, the system should work equally well when assessing single paths to larger regional scales. The following definition is proposed: Likelihood of avalanches is the chance of the start zones where the avalanche problem is expected to exist releasing within the forecast time period (Table 1).

- Magnitude: the estimated size (i.e. destructive potential) of the expected avalanches as defined by the Canadian avalanche size scale (CAA, 2024). Magnitude is a core component of avalanche hazard. The size definitions are widely used and accepted across industry.

- Amount of terrain: basically, the proportion or amount of terrain across the forecast area where avalanche problems are expected to exist. More terrain in the forecast region containing avalanche problems equates to higher hazard. For example, a day when the assessed avalanche problem and corresponding hazard is expected to exist only on southerly aspects in the forecast region (e.g. persistent slabs likely to Size 2.5) presents less overall physical hazard than another day when the assessed avalanche problem exists on all aspects. Put another way, if the assessment of avalanche problems results in more terrain features or start zones across the forecast region having a chance of avalanches, then it follows there will be more physical avalanche hazard across the forecast region.

- Complexity of the snowpack: this component of avalanche hazard relates to the number and type of avalanche problems expected to exist in a given snowpack structure, and how forecasters assemble them into an overall hazard rating. Simpler snowpacks that are less deep, contain less weaknesses, and are more homogeneous across terrain are less hazardous than deeper snowpacks with multiple weak layers that vary in the terrain. For example, a snowpack assessed as only having a storm slab problem (e.g. likely to Size 2) will behave more predictably (less complexity) and thus is less hazardous compared to a similar snowpack with additional deeper weaknesses such as a deep slab problem (e.g. possible to Size 3.5). It is important to note that this type of uncertainty with the snowpack structure is different than the uncertainty that a forecaster may have due to the lack of data or observations, which may result in lower confidence in hazard ratings.

A complete and thorough assessment of avalanche hazard across mountain terrain requires all four elements to be included. Rating and communicating the hazard assessment is the natural next step that avalanche professionals must complete.

OPERATIONAL AVALANCHE HAZARD RATING SYSTEMS

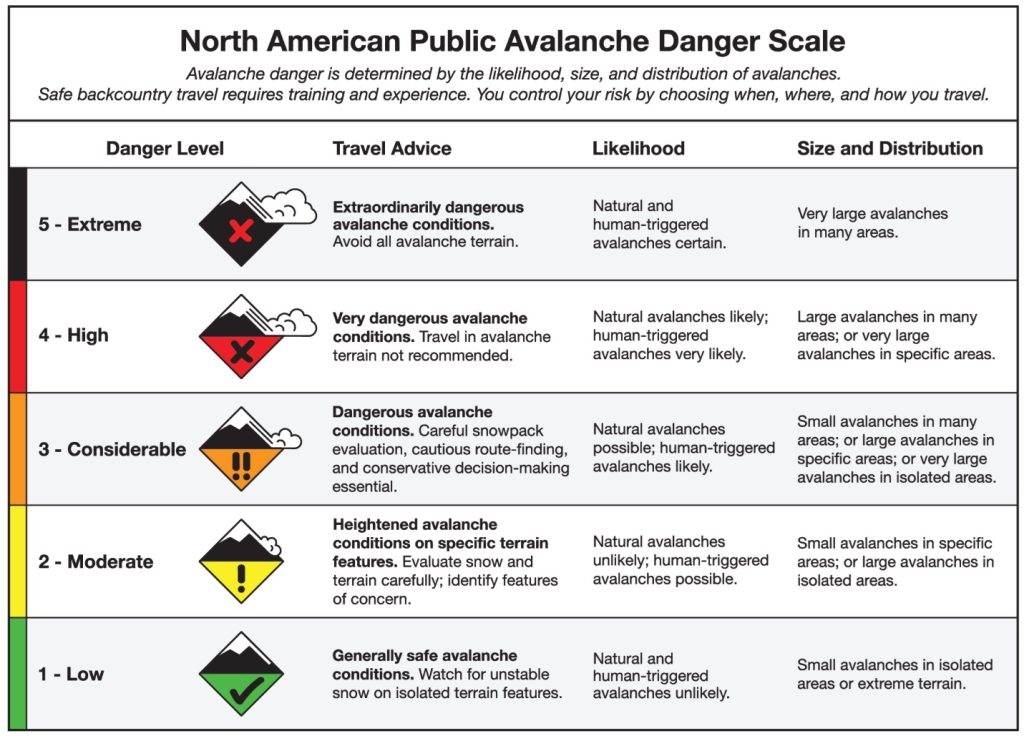

Hazard rating systems have proven to be an effective method for communicating the output of a forecaster’s hazard assessment (e.g. Statham et al. 2010a; SLF, 2015; EAWS 2016a; Avalanche Canada, 2024). While operational decision-making may rely more heavily on detailed avalanche problem descriptions, these descriptions are often too detailed for efficient communication amongst professionals. Ordinal five-level systems complete with descriptions of each level are common, although many industrial applications employ simpler three-level systems. For valid reasons, different operations tailor their hazard rating systems to their operational needs; consequently, rating systems often include risk management strategies. For example, the widely adopted North American Public Avalanche Danger Scale (NAPADS) shown in Figure 2 includes “Travel Advice” as its primary purpose is public risk communication (Statham et al., 2010). NAPADS was designed specifically for the element at risk (public backcountry recreationists), thus its description of the physical avalanche hazard is specifically tailored for communicating with public recreationists. For example, there is no indication of the complexity of the snowpack and how it is incorporated into the hazard rating.

REQUIRED SOLUTION

As mentioned, there are currently no established hazard rating systems that include guidelines for how ratings are to be applied and that effectively describe physical avalanche hazard independent of elements at risk. The Conceptual Model proposed by Statham et al., (2018) deliberately does not include a hazard rating scale, nor does it establish a deterministic link or process to arrive at a hazard rating. That is, the final step in assembling avalanche problem assessments into an overall avalanche hazard rating remains to be completed and is the next logical step.

A rating system effective for use by all avalanche professionals would be designed specifically to describe physical avalanche hazard across terrain and would be independent of any element at risk. Definitions for each hazard level would enable clear and effective communication of an avalanche professional’s assessment of avalanche hazard and would support risk mitigation strategies.

The definitions and the process employed to assign the ratings should be applied independent of the spatial scale of the forecast, include analysis of the four components of avalanche hazard described above, and would be built from clear meaningful language. These hazard definitions and associated guidance would likely reduce variation between practitioners’ evaluations, provide a learning resource for new professionals, and improve consistency in communication across the profession.

The rating system would be used widely to describe the raw physical avalanche hazard prior to consideration of operation or element at risk, and therefore, would be useful for the InfoEx community, taught in the Industry Training Program, and be integral to daily workflows for the majority of avalanche professionals.

REFERENCES

Avalanche Canada, 2024. Avalanche Canada – Glossary – Avalanche Danger Scale. https://avalanche.ca/glossary/terms/avalanche-danger-scale. Website accessed August 1, 2024.

Canadian Avalanche Association (CAA), 2024. Observation Guidelines and Recording Standards for Weather, Snowpack and Avalanches. Revelstoke, BC, Canada: Canadian Avalanche Association.

Canadian Avalanche Association (CAA), 2016. Technical Aspects of Snow Avalanche Risk Management – Resources and Guidelines for Avalanche Practitioners in Canada (C. Campbell, S. Conger, B. Gould, P. Haegeli, B. Jamieson, & G. Statham Eds.).

Revelstoke, BC, Canada: Canadian Avalanche Association. Carson, T., Larson, L., Martland, B., Jamieson, B., 2023. Why observers may not agree on the destructive potential size rating and a draft scale for more consistent ratings. Proceedings of the 2023 International Snow Science Workshop, Bend, Oregon.

European Avalanche Warning Service (EAWS), 2016a. European avalanche danger scale. European Avalanche Warning Service. http://www. avalanches.org. Accessed 2023.

Fischer, K., Jungermann, H., 1996. Rarely occurring headaches and rarely occurring blindness: Is rarely = rarely? The meaning of verbal frequentistic labels in specific medical contexts. J Behav Decis Mak. 9:153–72.

Friedman, J., Baker, J., Mellers, B., Tetlock, P., Zeckhauser, R., 2018. The Value of Precision in Probability Assessment: Evidence from a Large-Scale Geopolitical Forecasting Tournament. International Studies Quarterly, Volume 62, Issue 2, June 2018: pp. 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqx078

Rapoport, A., Wallsten, T., Erev, I., Cohen, B., 1990. Revision of opinion with verbally and numerically expressed uncertainties. Acta Psychologica. 74: pp. 61–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-6918(90)90035-E 000169189090035E.

SLF, 2015. Avalanche bulletins and other products. Interpretation guide. Edition 2015. 16th revised edition. WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF.

Statham, G., Haegeli, P., Birkeland, K., Greene, E., Israelson, C., Tremper, B., Stethem, C., McMahon, B., White, B., Kelly, J., 2010a. The North American public avalanche danger scale. Proceedings of the 2010 international snow science workshop, Squaw Valley, USA: pp 117–123.

Statham, G., Haegeli, P., Birkeland, K., Greene, E., Israelson, C., Tremper, B., Kelly, J., Stethem, C., McMahon, B., White, B., 2018, A conceptual model of Avalanche hazard. Natural Hazards 90: pp. 663–691.

Thumlert, S., 2024. The four key components of the physical hazard posed by snow avalanches across terrain. Proceedings of the 2024 International Snow Science Workshop, Tromsö, Norway.

Thumlert, S., Stefan, M., Langeland, S., 2024. Assessing and communicating likelihood and probability of snow avalanches. Proceedings of the 2024 International Snow Science Workshop, Tromsö, Norway. 2018