By John Woods, on behalf of The Land of Thundering Snow Virtual Exhibit Project

This article was originally published in The Avalanche Journal, Volume 103, spring 2013

Shortly past mid-day on January 15, 1909, a Canadian Pacific Railway passenger train snaked south along the precipitous western bank of the Fraser River north of Yale, British Columbia. Working in tandem, steam locomotives Nos. 496 and 841 pulled mail, express, and passenger cars through heavy snowdrifts and into the into the teeth of a blinding snowstorm.

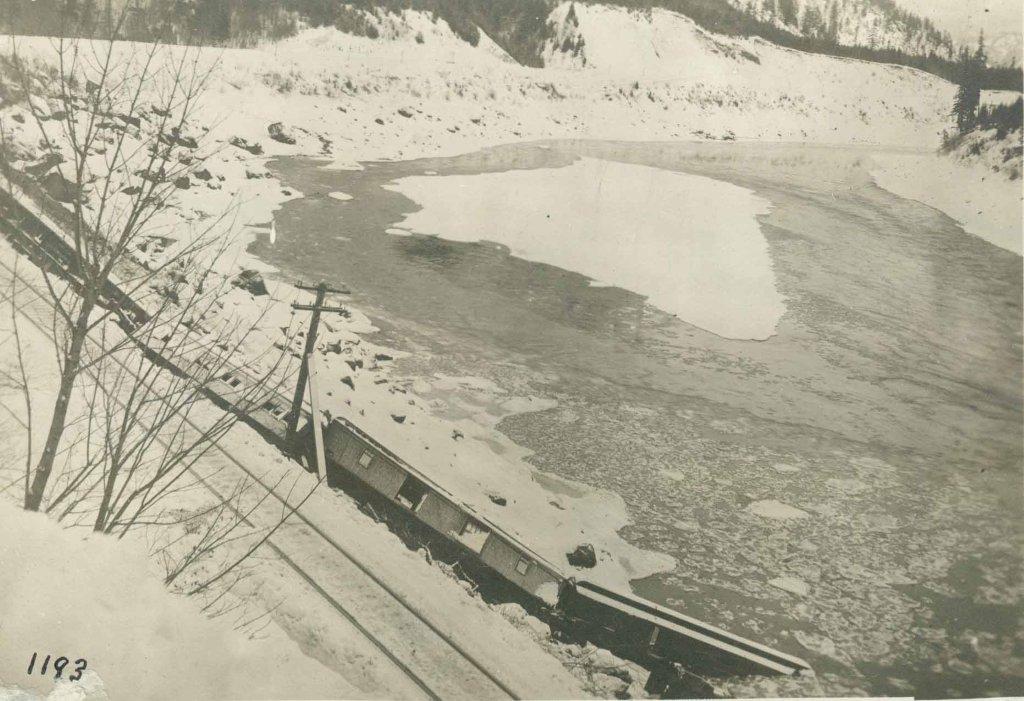

With little or no warning, the train ran into a snowslide already down on the tracks. Derailed, the head-end locomotives plunged towards the river, wrenching part of the train from the rails and dragging several cars downslope. In what must have been a cacophony of tearing metal and scraping rocks, engines and cars were sprawled across the steep river banks, some in, and some out of the water. Anchored by a heavy dining car mid-train, the following cars stayed upright on the track.

Quick thinking and action saved the lives of the three onboard mail clerks. Tossed in a jumble of mail-bags, they could hear water flooding their overturned car. Clad only in undershirts and overalls, they forced open the car door and escaped the rising waters. Miraculously, the firemen on the lead locomotives escaped serious injury; sadly, the engineers who worked beside them were killed.

News of the tragedy spread slowly because snowslides had torn up the trackside telegraph wires. But when word did get out, the grim tally included the two engineers, Hugh Carscadden and James Foster, along with more than 30 injured passengers and crew. As a sobering postscript, in the aftermath of the first accident, two passengers decided to inspect the disaster scene on foot and were buried by a second avalanche. They survived but needed to be dug out.

While less well-known for avalanches than the CPR’s mountain subdivision between Field and Revelstoke, or the Clanwilliam to Craigellachie area west of Revelstoke, the Fraser River route from North Bend to Hope has a long and continuing history of snowslide problems.

Caption: Clean-up operation of a CPR passenger train after a collision with slide debris along the Fraser River, January 15,1909 // Courtesy of the Kamloops Museum & Archives Photo #1193A

In modern terms, the passenger train disaster of 1909 happened at about Mile 19.3 in the Cascade subdivision of the Pacific Region—within slide path #8 between mile 19.0 and 21.0 (Latitude 49.6392 Longitude -121.4069). If you are travelling this area on the Trans-Canada Highway, as you pass through Sailor Bar Tunnel, the avalanche path is above you and the railway still runs in the open air beside the river.

Today, all maintenance railway crews working in avalanche hazard areas wear transceivers and are equipped and trained for avalanche rescue. Under the constant surveillance of an avalanche professional during the slide season, train and work crew activities in this slidepath are governed by work practices applicable to the daily hazard rating and whether the personnel are within or outside of a “track unit” (e.g., a train or plough). If the hazard rating is Low, then there are no work restrictions; if the rating is High or Extreme, no travel or work is allowed. When the hazard is either Moderate or Considerable, then only carefully defined activities are permissible. Given the conditions on January 15, 1909, it is unlikely that any trains would have been permitted across Slide #8 under today’s standards.

While we tend to think of avalanche accidents as situations where moving snow causes the damage, this incident illustrates that collisions with slide debris, given the right circumstances, also can be both destructive and deadly. In fact, railroaders have many stories to tell of times their trains struck snowslides and embedded objects such as rocks and trees down on the track. Sometimes the train would break through the debris, but other times the engine might get stuck or derail. Archives contain a number of photographs of locomotives literally plastered by snow after they bullied their way through a downed avalanche.

Recognizing the real and potential hazard of driving onto avalanche deposits, the Canadian Avalanche Centre has recently added a “collision with avalanche debris” category to the online incident file (Pascal Haegeli, personal communications 2013 January; see avalanche.ca/cac/library/incident-report-database/view ).

As more and more avalanche histories are added to the CAC database, new perspectives on both the character of snowslides and wide-scale storm events emerge. For example, recent database additions show that there were actually two fatal collisions with snowslide debris along the railway that day in 1909. The second incident took place about 256 track-miles (412 km) to the east when a CPR work train ran into a downed snowslide in Eagle Pass along the shores of Three Valley Lake (Longitude 50.934 Latitude 118.455). Engineer W. Coughlin and fireman G A. Hawkins died when their engine deflected into the lake.

Acknowledgements

The Kamloops Museum and Archives kindly supplied photograph 1193A as well as indexed notes on the Fraser River collision. Dylan Casola, Dan Sewell, and Mark Rickerby of Canadian Pacific were instrumental in locating the exact location of this incident and explaining the current Canadian Pacific safety protocols for the area.

Sources

Anonymous, 1909. Engine locomotive of C.P.R. freight train derailed by snow slide and sent over embankment. Daily Colonist (Vancouver) CI No. 31 Saturday, January 16, 1909 Page 1.

Anonymous, 1909. Plunged over bank of Fraser: wreck of passenger train on Canadian Pacific in Canyon east of Yale. Daily Colonist (Vancouver) CI No. 31 Saturday, January 16, Page 1.

Anonymous, 1909. Many on train near to death: wonderful escapes of people who rode on wrecked C.P.R. Express. Daily Colonist (Vancouver) CI No. 32 Sunday, January 17, 1909. Page 1.