Words and photos by Martina Halik

Note: This article initially appeared in The Avalanche Journal, Volume 112, Spring 2016

IT’S AMAZING HOW MANY THOUGHTS RUN THROUGH YOUR HEAD IN THE SECONDS WHEN YOU SUDDENLY FIND YOURSELF HELPLESSLY CAUGHT IN A MASS OF MOVING SNOW, HURTLING HEADFIRST TOWARD A STAND OF TREES.

OhSt-OhFk-ThisIsActuallyHappeningPullYourAirbag-ProtectYourAirway-Nononono!

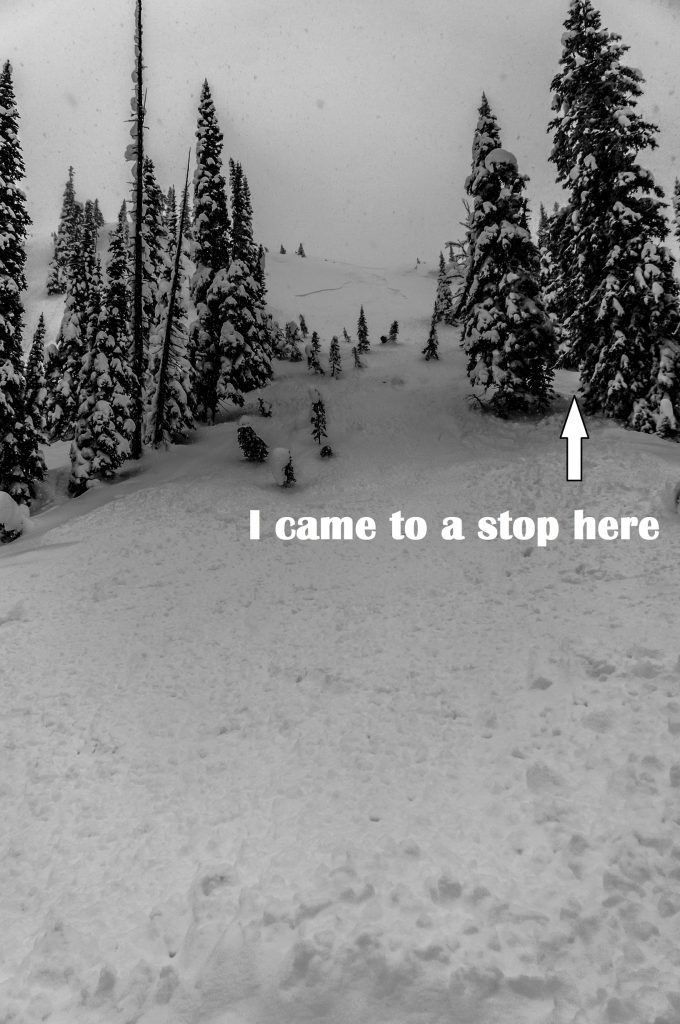

My head was pushed under the snow, I heard my airbag inflate, and I lost sight of the world. With one hand I tried to cover my airway and the other I stretched forward to brace for impact with old growth spruce. Seconds later came relief; I’d come to a stop, unburied in a stand of trees, as the rest of the debris continued for another 80m. Somehow I’d slalomed through the trees without hitting a single one, and came to a gentle stop when the snow piled up into a tree ahead of me. I pushed up out of the snow, began to hyperventilate as the adrenaline wore off, and shouted up to my co-worker Matt that I was okay.

I started berating myself immediately. What the hell was I thinking? Why didn’t I ski cut first? Why did I ski this slope when it was obviously safer to ski the skin track down? There were so many signs—shooting cracks and loud naturals rumbling in the unseen alpine. How could I have been so stupid?

The list of hindsight questions and exclamations continued as Matt and I searched for my missing ski and poles in the debris. Then came the really scary thought: I’m actually going to have to tell people about this. In that moment, it was the last thing I wanted to do. I just wanted to find my gear, get the hell out of there, and crawl into the safety of my bed. I started imagining the disapproving comments I was going to get from my supervisor, my coworkers, my friends and family. I work for Avalanche Canada! We’re not supposed to get caught in avalanches! It was only a size 1.5; it probably couldn’t have buried me. Maybe no one even needs to know?

Then I regained some professional composure, realizing I had a real opportunity to share a meaningful experience. If even one person could learn from my mistakes and it would help keep them safe, then it was worth the shame of owning up to some of my decisions leading up to this incident. It’s my job to promote education and awareness to the avalanche community, so it would be hypocritical of me not to share.

What I’ve learned in the last three and a half years of working in public safety is that simply telling someone how to be safe is only a fraction as powerful as a real life story—particularly with details, video, photos, and context from the accident. So that’s how I bullied myself into standing in front of the camera barely 10 minutes after getting caught in the avalanche. My airbag was still inflated and I mustered up an oddly cheery face despite the terror and flood of emotions I had felt moments before.

Currently, the five-minute case study video I produced has had over 10,500 views through blogs, forums, Facebook and other media venues. In our little world of avalanche outreach, we call that viral. Typically, our most successful blog videos reach less than half as many viewers. Surprisingly, feedback has been overwhelmingly positive. I’ve heard from sledders, skiers, AST providers, guides, and avalanche professionals telling me how much they appreciated that I shared my incident. The negative feedback I had feared so much in those early moments after the accident never really happened. My supervisors did not berate me for the decisions I made, my friends supported me, and my family did not beg me to stop going into the backcountry.

I understand how difficult it can be to share as a professional. Speaking with recreationists, I don’t believe the majority feel like they have as much to lose by sharing their mistakes in public. We work in a very competitive industry where we spend years building a reputation. Each day we maintain a careful balance of staying safe in a volatile environment, keeping the boss or clients happy, and also enjoying the incredible mountains we are lucky to call our office. There aren’t many other professions where our environment often has more control over our work than we do.

After hearing about my accident, my friend framed it well: as an accountant, if she misinterprets an income tax rule it means her supervisor will write a note on how to fix it, not throw her down a mountain in a mass of thundering snow hoping she pulls her airbag. Sharing and learning from mistakes is something done in all industries, just not always those with such serious consequences.

I don’t kid myself; I’m sure someone out there watched my video and thought I was an idiot. I don’t kid myself; I’m sure someone out there watched my video and thought I was an idiot. Despite any isolated negativity, I think it’s important as a community we continue to encourage disclosure and support the people who make it a priority to share their experiences.

Since I first entered the avalanche industry, I have witnessed great steps forward to becoming an open and transparent culture, but I also think there is always room to grow. In the end, all my accident cost was a $25 airbag canister refill and getting the living daylights scared out of me. Avalanche Canada and the public got an effective case study video in return. It wasn’t easy, but sharing my experience was a worthwhile process.

Check it out: