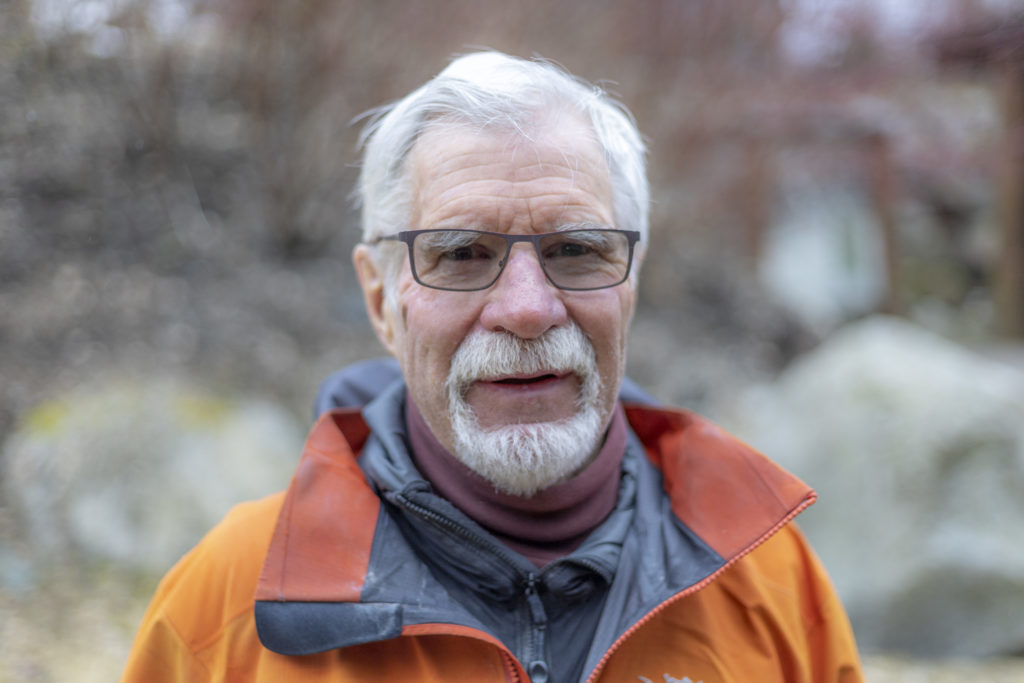

John Hetherington grew up in Ontario and began his career in the avalanche patch at St. Moritz, Switzerland, before joining the Whistler ski patrol in the late-60s. He enjoyed a lengthy career working in all aspects of the avalanche industry, including stints as a ski patroller, at Rogers Pass, as a consultant, and as a guide and owner of Whistler Heli-skiing.

John was one of the original members of the Canadian Avalanche Association in 1981. He was the President in 2004-05 and then the Treasurer during the pivotal period when the Canadian Avalanche Centre was formed (now Avalanche Canada).

This interview was conducted by Alex Cooper on Sept. 6, 2022.

Alex Cooper: Hello. My name is Alex Cooper and I’m here on behalf of the Canadian Avalanche Association’s Oral History Project. This project is for the CAA’s 40th birthday, and for it we are speaking with former Association Board members, particularly Presidents, key staff, and other figures to help preserve the CAA’s rich history through the eyes of those who worked to make the association a world leader in avalanche safety professionalism. Today, on Tuesday, September 6, I am joined by John Hetherington, who is in Whistler, B.C. Thank you very much, John.

John Hetherington: You’re welcome.

We’ll start going back to your childhood and just how you got interested in skiing or snow or winter—your early pathway into this industry.

OK. Well, I’m originally from Toronto. My parents took me to some place and that had a little ski hill and I got into skiing. Not very good at it, but I enjoyed it. Later, as I got older, and got my driver’s license, I could drive up to Collingwood with an old friend of mine and we skied in Collingwood.

Then, eventually, when I was at university, I got on the volunteer ski patrol, the Canadian Ski Patrol System, and volunteered at a place up in Collingwood. After I graduated from university, I went to Switzerland and managed to get on the ski patrol, what they call the SOS Dienst, in Saint Moritz and worked there for the winter. This was after university, so early 20s. I would have been 23.

OK. And had you ever been skiing somewhere like Switzerland or even Western Canada, in mountains like that?

No. Well, I’d skied in Quebec, at Mont Gabriel, and then the Laurentians had skied Mont Tremblant a few times. And I’d also been three times to Tuckerman’s Ravine in New Hampshire. The last time I was there, I was there for a month with a friend of mine. And that was an interesting experience.

The ski patrolling in Saint Moritz was interesting, and that was my introduction to some avalanche control. They used to make up bombs. They’d bring some tin cans from home, then we had a bucket of plastic explosives underneath the ski patrol shack and we’d spoon the plastic into the bombs and put a fuse in there and stuff it full of newspaper and that was your bomb. This only happened a few times, but we would throw these things, and sometimes even cause an avalanche.

Oh, wow! I’m curious, when was your your first experience or awareness of avalanches?

Well, that would have been it. That would have been it.

Because there’s no avalanches in Collingwood.

No.

What about at Tuckerman’s?

Tuckerman’s was different. The big problem there was the steepness of the place and you are more likely to fall and slide because it was, it was sort of ******** snow.

I know they have an avalanche centre there now, so I wasn’t sure if it was like that 50–60 years ago.

I don’t remember much in the way of avalanches. The big problem there was ice and, believe it or not, they said they had a rifle, a 30.06 I think, and they used to go and try and shoot the ice down. These were the park rangers.

Wow.

We got to know them pretty well. That was an experience, going up there and watching them shoot the ice down and then, you know, maybe rocks had come down and everybody had to hide while these rocks are coming down.

I grew up in Montreal, so we always talked about going to Tuckerman’s in the spring, but never made the trip there. I feel like I missed a bit of a rite of passage. It sounds like an interesting experience.

It was a very interesting experience. I got lots of stories about Tuckerman’s, right.

Alright, but we’ll move on because this is supposed to be about avalanches. So, you’re in Saint Moritz and you get your first exposure to avalanche control. What were your thoughts or reactions when you experienced this for the first time?

The beginning of the season, there was a two-day information course that they talked about all kinds of things, including use of explosives and avalanches and all that. Of course, it was all in German, Swiss-German, and my German was still pretty weak. To get the job, I’d had to interview in German. At the end of the interview, the guy spoke in English and said, ‘You know, my English is a whole lot better than your German.’ But I still got the job.

So, you went over there, you mentioned a couple of days of training. What kind of avalanche safety training did you get before starting? Was that it?

Well, that was all it was. It was almost like a lecture form, and then handling it toboggans and various other things. And it was all in German, so my memory of it is pretty weak.

What did you learn that first winter in Saint Moritz?

Well, I learned a lot of German. My German became good (it isn’t so good now through lack of use). By the end of the season, I learned a lot about Switzerland, about the local area, not a lot about avalanches. Just a very crude form of making up bombs and throwing.

My impression is Europe doesn’t do as much avalanche control, or avalanche control at ski resorts was more of a North American thing than in Europe.

A couple of the other places in the in the whole Upper Engadine Valley—there were several ski areas—I was just at one of them, and they had more serious avalanche problems. I think it was the Lagalb and Diavolezza and couple of the other ones, and they, the Swiss army would come in with some sort of mortar gun and shoot. But I was never involved in it. I was new.

You did your season in Saint Moritz and then next winter you went to Whistler, is that correct?

That’s exactly right. My first winter at Whistler, I went there to see if I could get on the pro patrol and I did. We did a sort of crude avalanche work there. We’d go around with some sticks of dynamite, you know, probably some Forsite 60 or something like that, some sort of rock dynamite. And they kind of learned where there were some avalanche problems. I’d go out with, say, Huey Smith, who was the head of the patrol back then, and throw some sticks of dynamite here and there. A few other places we’d stomp off avalanches, and that was my introduction to avalanche control.

OK. Whistler was much smaller then. There was no Peak Chair or Harmony Chair. What was the highest lift? The t-bars?

The t-bar was the highest lift, but there was an awful lot of hiking up to, say, the top of the Shale Slope and into the Whistler Bowl area and people would hike up to the peak. There were people who did it all the time. It was pretty regular, so even though there was no Peak Chair, people would go up there.

You’re there in 1967, so pretty early in Whistler’s history.

It was the third year that Whistler was operating, so it was pretty new and pretty crude.

What kind of systems were in place for avalanche control at that point?

Well, there were no systems in for avalanche control. If we thought there might be a possibility of an avalanche, oh, off the headwall of the t-bar or something, we might just close the t-bar and throw a few bombs or a few sticks of Forsite and say, ‘OK, it’s open.’ That was about it.

Wow. What kind of training do you get? I mean, now you there’s courses, like avalanche control blasting and all that. Did anything like that exist in that time?

Nothing like that existed. The one thing that that did happen was at some point during the winter—I don’t know how it all got arranged—but somebody came up from the United States with an early Avalauncher and demonstrated the Avalauncher. This was Monty Atwater, from Alta, who developed this gun. Somehow we ended up with one of these things and they showed us how to use it. We all said this is the most dangerous thing we’ve ever seen and put it away. I don’t think it came out for four or five years. It scared the heck out of us. If you’ve ever seen the way the old thing, the original Avalauncher worked, it was a scary business.

Oh yeah. What was it like? Like? Could you describe it in more detail?

The Avalauncher was actually a converted baseball pitcher that they used for batting practice. So, the big thing about it, it had a quick release and then that would blow the piston. So they figured they could put a cast primer in there. It was really a cast primer, you know, PETN stuff, but to make it explode, they’d attach a pull-wire igniter. Then there was a little cord inside this thing and you attach the cord to the pull-wire igniter and then put this stubby barrel on, load the thing up with pressure, and shoot.

And then you had to pull the barrel off to make sure the thing had actually fired out of the gun, the explosive had gone out of the gun. If it didn’t, you had 10 seconds to figure out what you’re going to do about it before it blew up and blew you up. That’s what scared us. And then we later heard that there been a couple of people had gotten killed, I think in Chile, with that gun, so we just put it away.

You did your first season at Whistler. How many years did you work there? I read you went up into mining ops after that.

Yeah. In the summer, after my first year, I got injured, so the following year, I didn’t do any avalanche control. The year after that, I went to Squaw Valley, for a couple of reasons. One of them was Whistler was applying to get the 1976 Olympics and I wanted to see what had happened to a place that had had the Olympics 10 years before.

So, I went to Squaw Valley, managed to get on the ski patrol there, and they were doing an awful lot of avalanche control. They didn’t really seem to know anything about avalanches and how they formed or anything like that, but they knew where the avalanches came down, so there was a lot of avalanche bombing going on. Everybody had routes that they had to take and it’s where I really got into pretty regular avalanche control.

Just going out hiking or skiing up and with bombs in your backpack or with the Avalauncher?

Yeah, exactly. Go up a lift with a packsack full of bombs and start throwing them.

I read Monty Atwater’s book, The Avalanche Hunters, where he talks about getting things ready for the 1960 Winter Olympics (in Squaw Valley, now Palisades), and there’s some good stories in there. It seems like quite the place to work at back then.

It was. And they had avalanche problems, there’s no doubt of it. Yeah, we used to see some big avalanches, but nobody really understood, why this? Why did we get an avalanche here now, but not over there? Or why now and why not a week ago? This kind of thing. There was no science behind it.

Were you curious about that, the why of avalanches?

I was, to just a certain extent. I did work up a Granduc mine for a while. But it was boring and we weren’t getting much snow and I was stuck over in Leduc, which was where the original mine was when the big avalanche came down and killed 29 guys, or something.

I had my own 75 mm recoilless rifle, which I would go out and shoot occasionally just for something to do. But we weren’t getting enough snow to really get any avalanches. I finally said I’ve had enough of this and I left before Christmas and went back to work.

That was basically just part of one season you spent up there or not even a season?

Not even a season, a couple of months.

Because, from what I’ve read, that area is notorious for big snow, but I guess you just hit it at the wrong time.

Yeah, I did hike up with another guy to the slope that huge avalanche came down that wiped out the camp and killed a bunch of guys. And it was just basically grass and quite an even slope. You could really see why there’d been a big avalanche there if you had any kind of weak layer. That thing was going to go. It’s a big, planar, smooth slope.

So, they had to build the camp in a totally different area and then drive a long tunnel and run a train through, so that’s where the miners got through to the mine. It became a very expensive operation and they eventually shut it down.

What did you enjoy about avalanche work? What kept you coming back? You mentioned, you went to university. I think I read you had a degree in business or economics or something like that.

Yeah, economics and political science.

Yeah. But then here you find yourself working in the avalanche world. So, I guess, what did you like about it? What kept you coming back?

Well, mainly the skiing. At Whistler, in the early days the skiing was phenomenal. You got big snow and not that many people. We were skiing powder a lot. Powder was an unusual thing and skis weren’t really made for it. They were long, skinny skis back then. You really had to learn how to ski powder and you really had to learn how to ski. It was the skiing I think that really got me interested, or kept me interested.

Yeah, what were you doing in the summers?

Whatever. Whistler was a brand new community. I know for two summers somehow I got a job putting in water mains in new subdivisions. We put the whole new water system into the White Gold subdivision. They were paying what was considered then really good wages. I think we were making like $4.25 an hour, which seems like nothing today, but back in the late 60s that was good money, believe it or not.

For how many years were you at Whistler as a patroller?

Well, I was one year there and then I rejoined the patrol in, I think it was 1973.

So, that was after the avalanche that killed four people?

Four people were killed in the Harmony horseshoe area, and I wasn’t working there at the time. I was on the ski patrol at Todd Mountain, which is now Sun Peaks. And so I wasn’t involved.

OK. But you came back. What brought you back there? Did that avalanche play a role?

No. I bought into, we’ll call it a house but it was kind of a shack. So, I had interest in a house in Whistler. That’s what brought me back.

OK. Did that avalanche in 1972, did it change the avalanche program at Whistler immensely?

Umm. A couple of years before that, or maybe a year before that, there’d been some guys on the patrol who really wanted to, upgrade their knowledge of avalanches and upgrade the facilities. They wanted to take better first aid courses and they really wanted to improve the whole ski patrol. But the mountain management said no. They didn’t want to go through this expense and they really didn’t think they had an avalanche problem at Whistler. So these guys all got fired.

And they had new guys for the patrol, you know, and they were decent guys, but they didn’t get much support from management. Then they had this big avalanche that killed four people and all of a sudden Garibaldi (Lift Co.), the lift company that owned Whistler, was faced with major lawsuits. They realized that something had to be done. So the following year, they hired a guy named Norm Wilson, who was the head of the ski patrol at Alpine Meadows in California.

So, he came up and spent a lot of time in Whistler and really set up the more modern avalanche system there. You know, using the ski patrol and how to do control, and set it up in a three zone—Zone A, zone B, Zone C—and how to do this and where the routes should go. So, the whole modern avalanche control system on Whistler came out of Norm Wilson’s recommendations. And that was the year that I got back on the ski patrol, so I was coming into a more modern situation.

Yeah. Did you appreciate that from a work standpoint and working there?

Oh yeah. And the year that Norm Wilson was there, the period that he was there, we had a very cold, fairly dry late-fall, early-winter. So there wasn’t a whole lot of snow and so there was a lower layer afoot we would have called back then depth hoar. Facets were occurring all over the place, and Norman said this may be the most dangerous avalanche places in North America.

Wow.

He was impressed by the place.

At what point did you realize you wanted to have a career in the avalanche industry? Did you know by this point or was it earlier?

It wasn’t necessarily I wanted a career; I was just doing it as I as I went along. I’m in my mid-20s, you know, and not a lot of thought on to the future. But it was interesting. And then sometime that year there was an avalanche course at Whistler. I think it was the second avalanche course ever held in Canada. The first one was at Rogers Pass; I didn’t go to it, but the second one was at Whistler and I attended that one along with, oh, Chris Stethem, who was also on patrol at the time. I think even Jim McConkey was there and various others. Peter Schearer put the course on and did all the teaching. They went on for five or six days. Very interesting. So that was my introduction to the scientific side of avalanche control and why you get avalanches, all that. There was a whole new introduction for all of us.

I guess up to that point you get a good idea of where and when avalanches might happen, but not really the why.

The where, we we kind of knew. The when was, yeah, most happen after a snowfall, and that was about it.

How long did you stay on patrol at Whistler for?

I was on patrol there until 1978. I was on patrol and then I became assistant patrol leader and then for a couple of years I was patrol leader. And then I moved on from there.

Moving to the CAA, I understand you were at the first meetings of the CAA, or what became the CAA in the early 1980s. Can you just talk about how you got involved or what led to you being involved and invited?

Yeah. Peter Shearer set it up, and he asked people who were involved doing avalanche work to come to a meeting at some hotel on Broadway St. in Vancouver. There were people from Parks Canada, from Banff and Jasper, and Whistler, and various other places. But there weren’t that many people involved in the avalanche problem back then. We went to this meeting and Peter wanted to start an association of people who were involved in avalanche work.

I can’t remember all the people that were there. I know Chris Stethem and myself were there. Clair Israelson might have been there. And there were some people from various other operations I knew. I knew a lot of these people back then.

Probably the Schleiss brothers?

I can’t remember if Fred and Walter were there or not. I can’t remember whether they were there. They might have been. And then I did work at Rogers Pass the winter of 1982-83—one of those winters. I worked at Rogers Pass, but they were putting an extension to the tunnel and for some reason the railway thought that there should be more people on the Avalanche team, which they called the Snow Research and Avalanche Warning Section.

For some reason I heard about this and applied for the job. I was living in Invermere at the time. I had moved out of Whistler, I was living in Invermere for about seven to eight years. So, I got a job at Rogers Pass, which was interesting, very interesting. And I got along really well with Fred Schleiss. And Fred would come and talk to me and tell me all kinds of things. He and I had met up before and he kind of knew my background, which I think helped.

And because I remember the guy who was nominally in charge of me and the guys saying Fred’s talked to you more this year than he’s talked to me in the last five years. I got along really well with Fred.

Yeah, here’s the first the first avalanche meeting that Peter organized. What was your thoughts going into that?

Well, I didn’t know what this was all about, this meeting. He just asked for people who are involved in avalanche work to come to a meeting. So, we went to this meeting and then we found out when we were there what the meeting was really all about. I didn’t have any forethought going into it.

What did you come out of that meeting thinking?

Well, OK, let’s start an avalanche association. But it wasn’t really me up to me to get the thing going. But yeah, you know, I was one of the very early members, I think, when it started in 1981. Yeah, I think I joined sometime in 1981.

You’ve been a member for the entire time. From your recollection, what were the main issues or the main reasons for forming the association?

Well, I think it was one so that you had a system of discussion amongst people who were involved in the game, so you could trade ideas back and forth and maybe deal with the products, you know, explosives. And what about this Avalauncher? Or any scope with the true artillery, like the 75 mm recoilless rifle. Maybe we could do more scientific courses. There was a whole lot of things like that, more possibilities, but you need an association to gather this information together so that people would know where to go to talk to people. And then you could have annual meetings and meet everybody, and get to know everybody who was doing some kind of avalanche work.

Yeah, which was, as you mentioned, a pretty small group. There would have been, you said Rogers Pass, the national parks, probably a few heli-ski operations, Whistler. Was there much mining activity back then or?

There was mining activity, and there was a couple of guys who worked at the Granduc and a few other places. But they were all way up north, and so whether they could join in on meetings or get involved in what was going on any kind of daily basis was pretty difficult for them.

What was your involvement in the CAA and those early years? Did you just go to the meetings or were you more active than just that?

I think in the earlydays I pretty much just went tothe meetings. I was trying to remember where they were. I think I got on some kind of committee, but I can’t remember what it was and what I did about it, so, I can’t really remember that part of it.

Looking at your avalanche career, I pieced together some of the early parts that you started up in Whistler and that you spent a season in St. Moritz. But you mentioned Invermere. Were you working in the industry from there?

Part of the reason I went was that Panorama had been purchased by an outfit out of Calgary and Paul Matthews, who owns Eco Sign Mountain Recreation Planners needed somebody to do a weather study there. So that’s kind of what I did. I was on the ski patrol at Panorama, but basically I was doing a weather study.

It was pretty interesting doing the weather study. I managed to get data from up and down the valley way back to World War One. And I had this huge accumulation of data and then I had to put it all together again and basically said what was fairly obvious: you don’t get much snow here, you need to put in snow making.

The manager said we don’t need snow making, but he was cheating all the time. He was giving his snow reports, and I put out proper snow stakes and systems and would argue with him (about his snow reports). But only a couple of years later, I think, they really did start putting in snow making because they realized they really needed it.

Yeah, they’re on that dry side of the Purcells. So, you’re the head of patrol or?

No, I was just on the patrol,

OK. So, you did seven to eight years there and then you returned to Whistler?

I only did, I think, one year of ski patrolling, and then I did a variety of things. I was living in Invermere when I worked Rogers Pass.

Shell Resources—Shell Canada Resources—had a drilling rig southeast of Fernie, tucked up right against the Alberta border. They were a few hundred yards from the Alberta border. And they realized they had an avalanche problem. There’s quite a long story, but they were going to put a camp in this one place and they put all the septic systems in there. And the health guy from Cranbrook had to come and inspect it, and he said, well, it’s a good place for a septic system, but you can’t put a camp here because you’ve got a huge avalanche path right above it. But these are all crop miners (flat-landers) from Alberta, so they didn’t know anything about avalanches.

And the guy who was in charge of the whole thing, he went to the industrial avalanche course sometime beforehand and realized this was a difficult problem, and talked to Geoff Freer, who was in charge of avalanches for BC highways at the time. Geoff knew that I was living in Invermere, so he recommended me. So, I had a consulting job with Shell Canada Resources to go down and handle their avalanche problem. And they did have an avalanche problem.

By that point, how much formal avalanche training had you had? You mentioned taking a course in 1973, but were there a lot of other courses you could take back then, or was with most of your learning on the job?

Well, the US Forest Service used to put on an avalanche school in Reno, Nevada, of all places, and I went to that. It was all done in a theatre, all inside work, there’s no outside work. There was a lecture and discussion and all that, but I went to that. And then I went to another course at Jackson Hole, and by then I knew some things and I actually introduced something—the shovel shear test. They’d never seen it before! And I introduced that. So, I actually became one of the instructors at this course that I was supposedly just a student at.

That was something developed at Rogers Pass that, or was that a Peter Schearer test?

Peter Schearer never liked the shovel shear test. I have a feeling it was a Rogers pass thing.

OK.

But no, he didn’t. Peter never did like the shovel shear test.

When was this that you were in Jackson Hole?

Probably around 76-77. Something like that, yeah. I think I took the course in Reno, that was 1974. So, I’m guessing say say ‘75, I was in Jackson Hole. So, I was accumulating knowledge as I went.

The other thing that happened was that Chris Stethem and I— he was the head of the Whistler ski patrol and I was the assistant patrol leader—another guy who started out in Alta—I’m not going to remember his name—he came up to Canada and he worked with Monty Atwater and he organized it so that a snow lab would could go up into Whistler in one of the maintenance buildings at the top of the chairlifts on Whistler and put Chris in charge of it.

And so, if we found if there’s a big avalanche, we’d go and do a fresh fracture line profile and take the snow from the interface and bring it into the lab and try and figure out what we were looking at. It was a cold lab. It was freezing cold. You’d come out of there almost hypothermic. You put the snow underneath a microscope and dial up to about 30 times magnification and take a look at the crystals to figure out what it was all about, if you could, yeah.

It was a learning experience. We didn’t know it. We didn’t know that much about it, you know, but you’re like, “What do you think this is this? Is this depth hoar stuff or is this surface hoar?” And you get to look at all these crystals. There was a book on crystals at the time. You kind of compare it and try and figure out what we’re looking at. It was really interesting.

That’s interesting. It sounds fascinating. So, I guess it tickles your educational brain a lot, learning all this new stuff.

Yes.

I’m curious, like, so you, you go down to Fernie to be a consultant, but what kind of tools did you have available for yourself to work down there, above this this drilling operation? You know, in terms of figuring out the avalanche frequencies and paths. Did you do any control work, that kind of stuff? What was involved in that?

There was a bunch. There were, I think, three big bowls that were pretty obviously avalanche snow and avalanche collectors, and then there was a fairly obvious avalanche path pretty close to the drill site, 300 metres away, maybe.

I set up a snow weather system. I brought in a Stevenson screen and thermometers and set up proper snow stakes. And then I trained a couple of guys who were in charge of maintenance at the camp to look at all this weather stuff. The idea was they’d phone me daily with the weather report. I was checking weather reports and I’d go down there once a week at first. I’d drive to Fernie and then they’d fly me in in a helicopter. I had a helicopter, so I could have a really good look at the whole area.

And a couple of times we got a problem with this avalanche path near the rig. When I was on patrol—I’m jumping back—but when I was on patrol in Whistler in the 70s, Chris Stethem decided we should figure out how to do avalanche control up high by throwing bombs out of a helicopter because otherwise we have to hike all the way up there with the sack of bombs and try and throw them in. On weekends, we were just really too slow.

So, he and I experimented throwing bombs out of the helicopter. And it seemed to work, but of course it wasn’t very long before WCB (Workers Compensation Board) heard about this and said, “What are you guys doing? Are you guys crazy, or what? But, if you think you’ve got a procedure, write out your procedures and send them down to us.” So, Chris and I sat down and set out a whole set of procedures and sent them to WCB and they said, ‘OK, these are the rules.’ What we sent down became the rules.

So, Chris and I actually made the rules for heli-bombing in Western Canada.

Oh, wow. I read the first heli-bombing was at the Granduc mine after the avalanche (in 1965), but you guys established it as kind of like a legitimate form of avalanche control?

Yes.

I did not know that. That’s fascinating.

Chris, when he set up his avalanche business, he was telling some client that he could fly around in the helicopter and throw bombs out of there. “Are you serious?” And of course he was able to say, “Well, I was one of the guys who set up the rules for this.”

That must have been exciting, but also a little scary. I imagine flying up there with the helicopter full of bombs.

It wasn’t that scary. We had good procedures. The problem was that when you were flying around with the door off, and we would tape our seatbelts so there’s no way you could accidentally open up the seatbelt clasp. The guy beside you would give you the bombs and the guy in the front had a stopwatch for timing. There’s four of us in the helicopter, but you’re doing all this flying around, and this stink of the fuses going off, and by the time you finish about an hour and a quarter later, we’d be wrecked.

And so, we had to make up rules that the top three guys in the ski patrol, you couldn’t have the patrol leader, assistant patrol leader, and one of the top controllers all going helicopter at the same time because your guys would be useless afterwards for next two or three hours.

Was it hard getting management to buy into that?

No, they liked it because we could open up the ski area much faster on a weekend. So, you know, you had to have good weather, but they thought this was great because the upper area opened up and there’s always a lot of pressure to get the upper area going.

So we’re just that much faster. The management thought this was great stuff and it was no more expensive to get the helicopter and fly around than it was to use the Avalauncher, because the Avalauncher rounds were not cheap.

Were you at Whistler when they installed the Peak Chair?

I just move back to Whistler from Invermere the year they built the Peak Chair.

Were you involved with that at all, the expansion of operations?

I don’t think I ever worked for Whistler mountain again because in the winter of 86-87, my first winter back in Whistler, Herb Bleuer—there’s a name you’ve probably heard.

I’ve heard that name.

He was a Swiss mountain guide and I knew Herb from various places, so I knew him quite well. And I was teaching an avalanche course. I started teaching avalanche courses probably in the early 80s, around in 1983-84. I actually wrote the weather chapter for the first avalanche course book because I had done a fair amount of study on weather and I’d done that weather study at Panorama, so I’d really had to look into it.

I was teaching an avalanche course with Herb Bleuer and he said, you should come out and do some heli-ski guiding with the company he was with. He’d started the company. And so I started heli-ski guiding in ‘86-87 on a part-time basis.

At one point. Herb was teaching a course, Mike Jacobson, the other owner, he was taking the course, and Ken Hardy, the other owner, he damaged his achilles tendon, and I was the only person left who could guide. So, I actually guided every day for about a week, and after that any time they needed an extra guide, I got a phone call.

By the end of the winter, I was pretty much on permanent. And then the next year I bought into the company and I was permanent, so I actually heli-ski guided for 25 years.

I was just about to get to that and ask how you got into guiding. Was that the second half of your career?

Sort of, yeah.

And were you still consulting on avalanche stuff during that time?

Once I got into the heli-ski game, at first it was rough, but we had clientele and we’re learning our terrain and learning all kinds of things, but I had more avalanche experience than anybody else in the company, other than Herb. Herb had a lot of experience. But then the company split the second year I was involved at the beginning of the year, and so Herb went with one company and I went with the other company, because I knew Ken Hardy from the past and I knew him quite well. I liked the way he was dealing with things.

So, the company I went with, I was by far the most experienced person in the avalanche problem. That meant I had quite a role in that company and stayed that way for quite a while. Setting out where to go every day and what runs we can ski.

I guess if you’re new, if it’s a new company, learning all the terrain is just such a sounds like such a huge job

Yeah.

And then getting weather information back then was really difficult. You couldn’t get a weather map on the computer. Back then computers were pretty recent stuff to have in your home and had a 386 processor. There’s no internet. You had dial up e-mail somehow, maybe. And so getting good weather information was really, really difficult back then. And I was always trying to do this and do that, and sometimes it worked, but usually it didn’t.

Where did it come from? Were you just doing field observations while you were out skiing, or did you set up a network of weather stations?

There was no point setting up weather stations. I think we put up some snow stakes, right. Like an HS stake someplace and a couple other snow stakes. We did put one up on Rainbow Mountain. We did put up some sort of weather plot that you get to occasionally because you can only go up there when you were heli-skiing and the weather had to be into it, and that’s where you had to go.

So it was pretty crude, I remember Francis Chiasson, he was on the patrol on Blackcomb, and he was really into computers in those days, and he set up some sort of weather bulletin board. He was getting weather information via Blackcomb and I could dial into that and get some of that information. But this is primitive stuff. I just did my best, but I was ahead of anybody else in the company of getting this weather stuff.

So how do you make it work? I guess by then you have two decades of experience, so you’re just relying on that, your of experience and instinct. And were you doing snow profiles while you were out, that kind of stuff?

Yeah. And, again, I was teaching avalanche courses. I was going to the meetings every year in Revelstoke, the Canadian Avalanche Association meetings, and there’d always be a meeting of all of the avalanche course instructors. We’d be getting the latest information and what everybody else is teaching, so it really kept me up-to-date on what was going on and what everybody else was thinking and how everybody else is teaching.

This was an annual meeting. Because I taught avalanche courses for over 20 years.

I was about to ask, because you mentioned that you taught courses in the early 80s. What courses were you teaching for the CAA?

Well, this was Avalanche Level 1. Maybe a six-day course. And that was about all that was being taught back then. And the occasional Level 2, which I took.

Oh my God! Ron Perla was the name of the guy—it just came to me—the name of the guy who set up the cold lab on Whistler. it was his cold lab, or maybe not his, but he had access to it and he set it up on Whistler, and put Chris Stethem in charge of it. And then Ron Perla was one of the main guys in some of the very early avalanche meetings and courses. I think I took what became the Level 2 course, the Avalanche Level 2 from Ron Perla that year. This was in1974, I think. It was called the Advanced Avalanche course. And then in 1980, I took a Level 2 refresher, which I did at the pass that goes from Salmo to Creston.

Kootenay Pass?

Yeah. We went up in that in the little gondola that the telephone companies had set up to access their relay station way up high there. And Peter Schearer and I think Herb Bleuer was involved in that as well. Maybe five or six students. And out of that I had a Level 2 course certificate. I think I’ve still got it someplace somewhere.

So, I want to get a bit more into your history with the CAA. You were at the first meeting, you’re attending the annual meetings, teaching courses. How else were you involved with the CAA over the years or decades? Then I’ll ask you specifically about your time as President in a second, but maybe you could just start by giving me a summary of how you were involved before that.

Well, I’d go to the meetings. Well, who knows when I started, but at first the meetings were held in Revelstoke. In Revelstoke, accommodation was difficult, meeting places were… They had a conference centre there, I think we used to meet someplace in the conference centre. They tried various places to have the meetings.

I don’t think I was terribly involved other than just going to the meetings, listening to people, talking to Peter Schearer. And then Bruce Jamieson came along and he was doing all kinds of experiments. There was pretty interesting stuff going on. Bruce’s students would get up and talk about what they were studying.

Then, what became the ISSW, the very first one was held in Banff, I think, in the late 70s, but I’m not really sure of my timing on this. Chris Stethem and I did a joint presentation on the whole avalanche control system at Whistler. It wasn’t called the ISSW at that point, it was sort of an avalanche workshop, but that’s what became the ISSW. That was like the very beginning of it.

So you attended those for a long time?

Well, I didn’t. There was a few I attended, but Chris has probably been to every one of them. But not me.

OK. How did you end up becoming President? You were president of the CAA in 2004-05? That’s what I have in my notes.

Yeah.

To me, that’s a fascinating time because that’s right after the big avalanches in 2003 and that’s when the Canadian Avalanche Center was formed as we know it. How did you end up becoming President at that point?

I think I was on a committee, and I can’t even remember which committee it was. It might have been the Professionalism and Ethics Committee. I have a feeling it was.

It was Clair Israelson who was Executive director and before him, I can’t remember. I can remember what the guy looked like but I can’t remember his name.

Yeah, there’s Alan Dennis for a bit. I’m not sure if there was someone in between.

Yeah, there was Alan Dennis.

But I remember after that avalanche, those avalanche situations in 2003. You know, I’m talking to Clair on the phone about it. And so I was involved somehow with something at the CAA at the time, but I can’t remember exactly, but I think I was on the Professionalism and Ethics Committee. That’s about all I can remember.

For the 2004 meeting, I was thinking that I’d kind of like to get on the Board and that, given my situation, I should be the Treasurer. It seemed to me that was the obvious thing for me. I mean, I had a background in economics, I was doing the accounting for Whistler Heli-Skiing and my wife’s an accountant. So I knew some accounting, which the previous treasurers, I was never sure whether they knew any accounting or not.

But then, before the nominations, Chris Stethem came up to me and said, “We don’t really have anybody to to run for President. And he knew that I’d served two terms on town council in Whistler; when Whistler first became a municipality in 1976, I ran for office and got elected.

They serve two terms there, and I also served the term on the council in Invermere, so I had some political background.

And so, he said, “John, we got to have you as President, OK?” It’s not really what I wanted to do, but if you insist. So that’s how I got to be President. Chris and I were old friends. We’d worked together and we done all kinds of things together.

Did you have a sense of duty, like after being part of the organization for so long? Like, “Oh, maybe this is my time?” Was that involved at all?

Chris asked me and I was already thinking of getting on the board anyway, thinking more of coming on as a Treasurer, not as President. Maybe that’s what you really need. OK. I guess I can do it. I don’t know.

I’m aware there was something called the Canadian Avalanche Centre before this, but this was a wholesale, a new development that something really focused on public avalanche safety.

Yeah, well, their always has been sort of the Canadian Avalanche Centre, but it was mostly just a name. It was trying to put out information and it was totally funded by the CAA and the CAA was totally funded by members dues. It felt like this Canadian Avalanche Centre should be its own thing and should eventually not have to rely on the members’ dues or it’s revenue?

And I think the the Canadian, the Canadian Avalanche Association, sorry, the Canadian Avalanche Centre became a society before I became President, and I think Bill Mark was President before me. I think I’ve got that right.

I have a list here. Just give me a second and I’ll pull it up…

Yeah, Bill Mark was president for three to four years before you.

Yeah, I thought so. And it was during his time as President that the Canadian Avalanche Centre was incorporated as a non-profit society both in British Columbia and federally. And so you had this CAC with unknown funding, still pretty much funded through CAA members dues. But the whole point of the CAC was to put out sort of public avalanche bulletins. It was to put out information to the public about avalanches and to be kind of the centre for public avalanche situations, whereas the CAA was the association for people who worked in the avalanche situation.

So, it was quite a quite a two really different kinds of things, you know. At the CAA, you were expected to keep up your knowledge and know everybody who’s in the business and all that kind of thing, where the CAC was for public information.

You were President kind of as the CAC has formed and so you have to manage, you’re involved in both those, both those organizations, one that’s just getting started and one that’s pretty well established by that point. What was that like? What were the challenges you faced?

Well, I mean, I was President of both organizations at the same time. I remember—I’m not sure exactly how all of this happened—but there was some kind of a vote as to the future of the CAC and I think there was a a strong feeling that the CAC should be made independent sort of almost immediately. I think what we were proposing was that the CAC should gradually become independent and work towards independence over, maybe, I don’t know, four or five or six years. And that was put into a motion and the motion was turned down.

So, we had this negative vote on what we were hoping to do. Then I, as President, I don’t know what are we going to do about this, and started looking into the BC Society Act. And because I was used to looking at legal documents, having been on council for six years, I can understand it. So I went through the whole BC Society act and realized that the Canadian Avalanche Association was seriously offside the BC Society Act in that we had far too many non-voting members. In order to have a vote at the CAA, you had to be a Professional Member, but you could be a member if you’re taking your CAA Level 1 course, but you didn’t get the vote.

And we were way offside in the percentage of non-voting members, like way offside. So, I remember talking to Clair Israelson about it and he was shocked. Nobody ever looked at the BC Society Act before. And, we gotta do something about this. And so I did quite a rewrite on the CAA Bylaws.

Again, something I was more used to doing that than anybody else because I’ve been on councils. When I was on Whistler council, we’d had to write all our own bylaws because we didn’t have any. We started out and didn’t have a single bylaw. We’d meet in the mayor’s basement and go, OK, what are we going to do about a subdivision bylaw or a zoning bylaw? A sign bylaw or a parking bylaw or garbage bylaw and all of this stuff? I’ve been through it all.

And so I did quite a re-write on them. So, there we had another proposal at the next meeting saying the CAC should become independent, I think in a five-year process, and that we had to make anyone who was a member but only had a CAA level 1, they had to become voting members. I think it was Bruce Jamieson who said, let’s call them Active Members. So, we have Professional Members and Active Members, and the Active Members got the vote so that we were no longer offside with the BC Society Act. And that whole set of motions passed.

Even the gradual change of the CAC, once we presented it this time, we presented it better than the first time around and that passed as well.

There’s quite a change, you know, to the CAA there. But I was really, we had a meeting at some point with our, now they call them CPAs but they had a different term for them back then. He was our accountant and he was talking. I had a meeting of the CAA executive about our financial situation and our accounting practices and all of this kind of stuff. And it turned out the meeting was between him and I, because I was the only one who understood what he was talking about. At the end of the meeting, he said, “Well, you’ve got one guy on your executive committee who understands all this accounting and financial stuff, but it isn’t your treasurer.”

And so at some point after that, I think it was Steve Blake who was Treasurer, we decided to change positions. He’d become President. I found I just didn’t have the time to be President. I was doing all this heli-skiing stuff, and that was plenty for me. It just wasn’t working for me, and Steve would be better. He was a warden in Jasper and was more likely to have time and access to computers and telephones. Meanwhile, I was out heli-skiing and I didn’t have access to anything. So, he and I switched over and I became Treasurer and he became President. And I won the professionalism award for being willing to do this, and became the Treasurer.

I was in a unique situation as a Treasurer because I was not only involved with the day-to-day avalanche work, but I was also a company owner because I was one of the owners of Whistler Heliskiing. So, this put me into quite a unique situation to be able to go, this is what corporations are thinking about that hire all you guys, other than all the Parks Canada guys that are with the CAA. And this is the economic and accounting side of it as well. There was nobody else in that situation who was a member of the CAA and really understood the financial side, which is so important. I used to tell Clair Israelson things like.

Which you have to remember is, as a non-profit, you’re really interested in the missionary work that you’re going to do, but some of it’s pretty expensive, so you’ve really got to keep an eye on the revenue side, which is the side that tends to get ignored by non-profits that have this missionary situation. And I used to tell him that fairly often.

I used to go through the financial reports on a very regular basis with the financial controller for the CAA. I used to go through it with her and go, ‘OK, what’s this? What’s that?’ And because I understood it, I knew what was going on.

Yeah, that economics degree you did back in the 60s stayed with you and definitely helped you played a role?

Yes, it did. And I remember when I gave my first Treasurer’s report at the CAA meetings Janis Johnson—she was an instructor at UBC, I think, and she taught a lot of people at the CAA about how to teach avalanche courses, she was pretty important person—she came up to me and said that was the first Treasurer’s report I’ve ever understood. Now the other Treasurers, I don’t think really understood accounting, so they didn’t really know what it was all about.

How long were you treasurer for?

I was on the board for six years, so I was President for, I don’t know, a year and a half or something. And then the rest of the time I was treasurer.

OK. When did you stop being involved with heli-skiing? When did you retire?

Oh boy. I retired when I was 68. I know I worked there the Olympic year, 2010. So it might have been sometime in the following year, is when I finally decided I’d had enough.

Have you been involved in the industry much since then?

Nothing. I haven’t been to any of the CAA meetings because (Chris) Stethem and I, he always had some trip or something. I’d either go back to his summer cottage in Eastern Ontario, or we would do some bike trip someplace in Europe.

One question that we’re asking people is, from your perspective, what are the most significant achievements of the Canadian Avalanche Association over the years? That’s a big question, but what are your thoughts there?

Well, I think the avalanche education systems. First of all, you had to have a Level 1 and then you had the Avalanche Level 2. Then you got all the recreational avalanche courses—Avalanche Skills Training, I think they call them now. I think all of that has been one of their huge achievements.

The other big achievement was the OGRS, which really gave the guidelines for how you do all kinds of things and how you record it. I think that was a major, major achievement and it unified how everybody was working in the business in Canada. Whereas we were looking at the United States and each state that had an avalanche problem, thought their system should be the one that should be the national system. They kept arguing amongst themselves until finally they said, “Why don’t we just buy the Canadian system and we’ll we adapt it to our situation?” Which they did.

Were you involved in OGRS and creating that?

No, I wasn’t involved in it, but I was kind of there. I went. There was an ISSW meeting in Jackson Hole when I was President and I was there for that. That’s when they were really talking about purchasing the Canadian OGRS. That was an interesting meeting.

Talking about the impacts of the CAA, you said you haven’t been involved for a decade now. But do you have any thoughts about the challenges for the CAA looking to the future?

I really don’t know because I haven’t been involved for so long. I don’t know what their challenges are. There’s been a whole generational change. The guys that I knew who were on the board and head of the committees and all that sort of thing, a lot of them have retired. If I went back there, back to a meeting, I know Joe Obad and Bruce Jamieson probably shows up. But anybody who’s actively involved, I don’t know whether I know them. Things are changing fast. There’s a lot of people.

I think there’s 1,200 members now. I don’t know how many there were back then.

You were in the industry for 45 odd years. What were the most important developments over those years?

I think the association itself was important by gathering people together. So you had one organization for all of Canada. I remember when Dominic Boucher came out from Quebec because he set up the whole avalanche control system in the Chic-Choc Mountains in the Gaspesie in Quebec. He’d come out from Quebec and at first he could hardly speak any English, but his English kept getting better. And then he brought out friends of his who were more bilingual, guys he was working with were more bilingual and he became part of it. Newfoundland somehow got involved, so it became a pan-Canadian organization that started out in B.C. and Alberta.

So I think that was important. The education thing was really one of the big, big deals. Various other countries have adopted the CAA’s education system. It started out with New Zealand, but then Japan. A couple of guys who worked for Whistler Heli-skiing translated the course manual into Japanese.

We’re teaching a course in Australia right now, of all places.

Do they get enough snow to have an avalanche?

Apparently they do.

My son worked in Australia for three years. He says you don’t go to Australia for the skiing.

I have one more question for you. Well, I have two more. The first one is, how did you get the nickname Bush Rat?

There’s several stories as to how I got the name Bush Rat and I don’t know which one is true. It goes back to the early 70s.

Is there one you want to share, or your favorite one that you can share?

Who knows? One of the stories I can say is I had a very good friend who was originally from Montreal, Rene Paquette, and he was known as the Pack Rat, and I became the Bush Rat.

Alright, I won’t press you.

That’s one of the stories. There’s several others.

I mean, we’ve covered a lot. I’ve kept you longer than I thought I would. Do you have anything else you want to add? Is there anything I missed or any, last words?

I don’t think so. Although the one thing I did do was, after I was retired, I talked to whosever treasurer. The treasurer after me used to phone me every now and then to find out how to do things because he didn’t have any accounting or business background like I had. But I said at some point you’ve got to set up a membership for retired members because the dues are too expensive. Retired members were not really getting anything out of it other than maybe The Avalanche Journal. And so I became the very first Retired Member.

There you go.

There’s probably a few more now, but I was the first one because I really insisted that they needed that membership category.

Great.

Well, thanks a lot for your time. I really enjoyed this.

I’m glad we were able to connect, especially on video.

Yeah, that’s good. And it really forced me to, I had to write a bunch of things down because I had to dig my memory up here because all of this stuff is way in the back, hidden in my memory somewhere.

And it just occurred to me, I didn’t ask you about InfoEx but I guess I can save that for other people.

The InfoEx, there’s an awful lot of stuff with the InfoEx.

Well, thanks so much for your time. Hopefully, maybe I’ll get to meet you one day. You show up at a meeting again maybe.

All right. Have a good day, John.

Thank you. You too.