Tyler Carson on proposed revisions to the Canadian avalanche size scale

By Alex Cooper

The Canadian Avalanche Size Scale was introduced in 1981 by David McClung and Peter Schaerer. They developed a system to report avalanches on a scale of one to five based on their path length, deposit size, run length, and destructive potential. In recent years, a group including Tyler Carson, Bruce Jamieson, Lisa Larson, and Brendan Martland have been working on revisions to the avalanche size scale. They presented their ideas at the 2023 CAA Spring Conference, then conducted a survey of avalanche professionals over the summer. Tyler then presented an update at ISSW 2023 in Bend, Oregon.

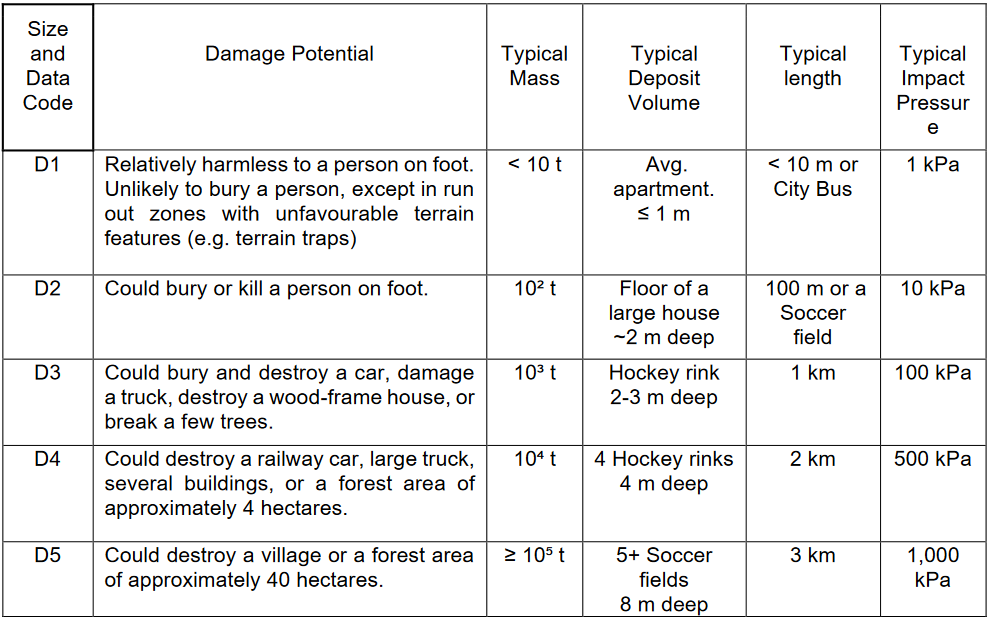

Their proposed update maintains the five-level scale, but adds deposit volume as a measure of avalanche size, and changes several of the descriptors of destructive potential. I spoke to Tyler, the Snow Safety Supervisor at Fernie Alpine Resort, on Oct. 30, 2023, about why they feel the size scale could use an update and the work he and his group have done to this point.

(Note: this interview has been condensed for space and edited for clarity. Watch the video below for the full interview.)

Alex Cooper: Where did this idea to review the size scale originate and what’s been the process so far?

Tyler Carson: I think originally it started with Bruce (Jamieson), Montse (Bacardit Penarroya), Ethan Greene, and Ian Tomm’s work back in 2020, where they were giving a more visual method of estimating avalanche size. From there, it went to a presentation Bruce gave at the Elk Valley Snow Avalanche Workshop, where he talked about this more visual method of estimating avalanche size, and whether different observers give different sizes of avalanches. And then it moved on to our presentation at the spring meetings, where we discussed whether we should include escape skill and terrain traps into the size scale to allow for better estimation. And then on to ISSW, where we presented a paper about how there are two different things that really affect how people make estimations of avalanche size, how they can be inconsistent, and some ideas on how to make it more consistent.

What do you see as the issues with the current scale?

I think the current scale doesn’t provide enough tools for practitioners to provide good estimations of avalanche size. We’re getting a discrepancy in size due to a lack of tools and a lack of clarity of language, is really what it is. Currently we do have a few issues with the actual volumes and measures of sizes, but what we’re really trying to tackle here is how we communicate them and how we give people the tools to

communicate them.

OK. You mentioned people are talking about size in different ways. What are some ways that people might overestimate or underestimate avalanche size?

We’re often affected in our estimation of avalanche size through emotional response. If I’ve been caught in an avalanche or exposed to an avalanche, I may overestimate its effect just because of my personal fears, my stressors. We also tend to over or underestimate due to our workplaces and the frameworks we work within. So, we can over and underestimate that way. When we’re on foot and we get caught in an avalanche, we tend to overestimate. But then when the perspective is changed and we’re in a helicopter or at a distance, we often tend to underestimate. So, trying to give people some tools to help with that, I think would make a difference.

Why is it important to get the size right? Why is that so important to communicate properly?

It’s important to communicate properly and accurately because it’s a tool. When we talk about size of avalanche within the Conceptual Model of Avalanche Hazard, we need to understand what is out there. We can’t apply risk treatment appropriately if we don’t understand what the actual size is that we’re facing is. So, that’s one of the biggest ones for me.

I have a very diverse group of coworkers and some of the newer workers—and some of the more experienced workers—have their own biases to avalanche size. Because I personally know them, I can adjust for their bias. But if I was being communicated to by somebody else that I didn’t know, maybe another team somewhere else, or if I’m reading the InfoEx, I don’t know that team or that group’s bias.

You presented a couple of drafts of your proposed scale—first at the Spring Conference, there was more feedback received after that, and then you presented it again at ISSW. Can you talk about some of the elements of that the draft you’ve proposed. I’m interested in some of the new descriptors you had for some of the sizes. Looking at size one avalanches, it says, “Relatively harmless to a person on foot, unlikely to bury a person except in runout zones with unfavorable terrain features.”

How did you come up with that descriptor?

That descriptor came from some discussions we had. The “on foot” we added because we want to help people to visualize someone at their highest vulnerability. When you’re on skis or on your snowmobile, you are more vulnerable than you are when you’re in a snowcat, for example, but you are less vulnerable than you are when you’re on foot. As a human being, being on foot in avalanche terrain is your highest level of vulnerability. Hanging from ice tools is right up there, too.

The other descriptors that came along with the unfavorable terrain came from the European Avalanche Warning Service and from their descriptor. We’ve since readjusted and re-tweaked that. We found it was a bit wordy and we’ve taken big chunks of that out, and left some of the parts that we felt were important to the structure of that in.

OK. So, what wording did you use instead?

For draft two, we’ve gone to, “Relatively harmless to a person on foot except in terrain traps.” Just cleared out a whole bunch of stuff.

OK. So the terrain traps being the main thing, which is something that I feel they teach in AST courses—a size one isn’t harmless unless you get swept into a gully or over cliff.

Yeah. Our discussions on this really have come from the fact that it’s really hard for people to grasp “relatively.” Relatively is a funny word for people. When we say “relatively harmless,” people automatically think harmless, and it’s not harmless. It’s just less harmful than a size D2 avalanche, which is something we have a hard time grasping.

For size one, you mentioned a person on foot. Same with a size two avalanche, you specify it “could bury or kill a person on foot.” That “on foot” addition is not part of the scale now. I wonder—compared to people on skis or snowmobiles—where does the part about being on foot differ and why add that in?

Just the poor mobility. On skis, we can move fast. Even with your skins on, you can move faster than postholing. If you’re on skis or

a snowmobile, you tend to be active in the terrain and know what’s going on. Whereas, if you’re an industrial worker who is outside of your bulldozer, you may not know how to avoid or move so that you can reduce your exposure to avalanches, or even be able to for that matter. So, being on foot, I think we’re just really trying to get across that it is at their highest level of vulnerability.

Yeah. And then jumping ahead, for size three and four, I see the draft descriptors are largely the same. But for size five, you propose removing the phrase, “largest snow avalanche known.” Why take that out?

The “largest size snow avalanche known” tends to bias people. They don’t want to use it because you see a big avalanche and you’re like, “Oh, is this the largest snow avalanche known or the largest one I’ve ever seen?” It may or may not be. But what it is, is the size five avalanche fits

within a descriptor of size, of impact pressure, mass, volume, those sorts of things. And we want to make sure that people are making that decision that this is a size five avalanche by using those descriptors, and being able to estimate that and not going, “This isn’t the largest snow avalanche known.”

Mark Grist and crew gave a great presentation talking about it and how it’s hard to say it’s a size five. Johann Slam has lots of opinions on this and I’ve had some good conversations with him, where he’s just like, “Yeah, it’s a size five.” And I think we just need to be able to more readily put that measure on an avalanche.

Yeah, I think it’s a good point because I suspect the largest avalanches people experience in the mountains of Western Canada are not close to the scale of the largest avalanches known, which are massive, glacial, rock, snow, and ice events.

Yeah. You were at the ISSW with me and you saw the presentation from Langtang . The snow didn’t melt from that village for four years, I think is what (Austin Lord) said. So, yeah, that’s how deep and thick that avalanche was.

Yeah, for sure.

And then you’re adding volume and volume descriptors to the scale. I was interested why you’re adding volume and also how you came up with these descriptors such as, “Fill the floor of a large house two metres deep.”

That’s all Bruce, Montse, Ian and Ethan. We really just took that information and placed it in there, and then we have tried to tweak it a bit. There has been some concern about equity and about how people don’t understand what a hockey rink looks like, or what an apartment looks like. You know, there’s a mismatch there.

And these are just ideas really, where we’re trying to find the best possible. We’ve discussed how maybe adding a glossary where it says, “Two tennis courts is a hockey rink,” or something—some sort of equivalency scale so we can paint the best picture for all the people. And the volume descriptors are a good one because it’s an easy one to visualize, right? It’s hard to visualize mass. You’ve had a rain-on snow-event and you’ve had a dry snow avalanche. The piles will often be the same, but the masses will be different, and so estimating the mass might be tough. Giving someone another option to look at it doesn’t have to be perfect. It may not be a perfect measure, but giving people a tool to look at the avalanche and go, “OK, the volume here should be a size two, or it should be a size three.” It’s just giving people more tools so we can hopefully be more consistent.

One thing about the size scale is it’s used both by professionals to communicate with each other, but it’s also a public communication tool. Is that a challenge figuring out how to make this work for professionals and recreationists?

I think that it is a challenge. It’s definitely front of mind for all of us because it is a scale that is shared between recreationalists and workers. The difference between an experienced recreationalists and a new or young worker, it’s a very grey zone. It needs to be available and usable by someone who is brand new, and by someone who has tons of experience, period, whether they’re a professional or a worker or a recreationalist.

You’ve presented this now a few times and done several revisions. Where do you go from here?

We are in the refinement stage of where we’re going with our size scale. The timing seems to be good. OGRS (Observation Guidelines & Recording Standards for Weather, Snowpack and Avalanches) is due for revision here. We’re going to submit it to the CAA Technical Committee and then allow them to review. We’ve decided we’re going to leave the actual physical dimension measures of avalanches, whether it’s mass, volume, those sorts of things, to those guys. They can research it and deal with that.

We’re worried more about making sure our estimation wording alignment is as close as possible. I had a talk with Scott Thumlert (Chair of the Technical Committee) about where to go next with this. We’re going to try and move this forward in the next couple of weeks to him and pass it on to them, and then be there if they have questions for us. And hopefully it makes a difference. And if not, we’ve made an attempt.

Is there anything else you’d like to say?

If anyone has any feedback, feel free to e-mail me: tcarson (at) skifernie.com. Reach out to Bruce, Lisa, or Brendan, any one of us, and we’ll take any and all feedback. You know, you get some real rogue stuff out there, but sometimes it makes lots of sense and sometimes it’s something you’ve never even thought of.