By Ryan Buhler, Forecast Program Supervisor, Avalanche Canada

THE 2022-23 SEASON in the Avalanche Canada forecast office was dominated by the complexities of public avalanche forecasting with a deep persistent avalanche problem. The season would ultimately end with 11 out of the 15 Canadian avalanche fatalities being associated with deep slab avalanches. This is comparable with other years that had notable deep persistent slab problems, such as the 2002-03 season, when 14 of the 29 fatalities were attributed to deep slab avalanches, and the 2008-09 season, when it was 17 of the 261. This article outlines how this exceptional winter led to us adapting our approach to public avalanche safety messaging and the challenges we faced.

EARLY SEASON

As early as the first weeks of December, it became apparent we were dealing with an unusual snowpack. We heard concerns from the guiding community, who made comparisons to historic seasons like 2003 and 1993, and it became clear that we were about to embark on a challenging season. Low early-season snowfall, long periods of drought, and two Arctic outbreaks in early-December resulted in the formation of a prominent basal weak layer in much of western Canada.

The season’s snowpack is examined more closely in my blog, “A Technical Review of the Formation of the 2022-23 Deep Persistent Problem,” published in early-April. Although we did not yet have a widespread slab or an abundance of avalanche activity, we understood the need to

prime the public for the problems lurking in the snowpack. We issued our first blog on December 9 to highlight the unusual persistent weak layer and discuss the factors that might cause a tipping point for widespread avalanche activity on this layer. A few days later, we reached that threshold and issued a second blog, warning about the potential for touchy persistent slab avalanche activity.

Shortly after that, Grant Statham of Parks Canada issued a blog titled “Persistent to Deep Persistent – Why the Switch?” that explained why the forecast regions in the Central Rockies had already made the transition to the deep persistent slab problem. Although we had started messaging around a persistent problem, Grant’s blog was the first product that alerted the public to the possibility of a season-long problem and the need for a different mindset throughout the winter. This was a signal that we needed to shift our approach to messaging for the remainder of the season. While advising an entire season of restraint and extra caution was essential, we knew it could be a hard sell to the public. Upon re-reading that blog at the end of the season, I found it was quite prescient and laid the framework for many of the concepts we would explain to the public for the rest of the winter.

NEW YEAR, NEW CHALLENGES

Avalanche activity on the basal layer began to occur in mid-December, but it was the major storm at the end of the month that marked the start of widespread large avalanches (Fig. 1). This cycle included wide propagations across multiple features and instances of remote triggering. Given the combination of this major storm and the potential for a busy New Year’s long-weekend, we issued a Special Public

Avalanche Warning (SPAW) with Parks Canada for most of the interior regions on December 28. During this time, many of the Avalanche Canada forecast regions still referred to a persistent slab problem with large surface hoar being a major component of a complex November weak layer throughout the Columbia Mountains.

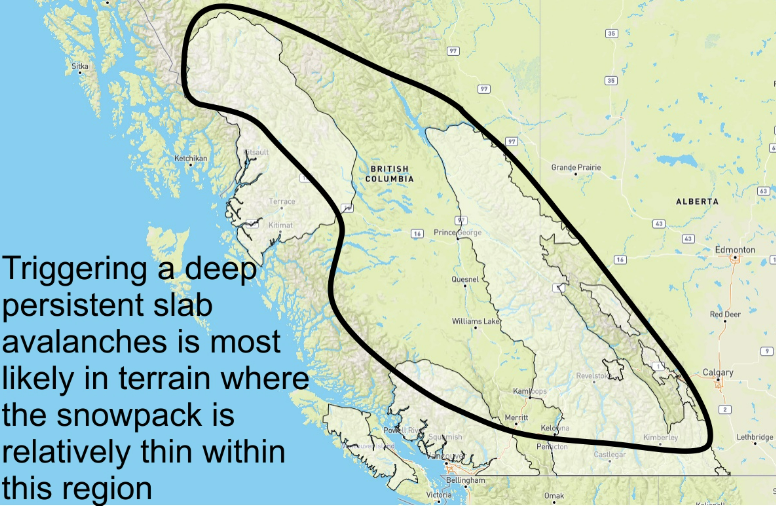

By January 5, we had transitioned to categorizing the November weak layer as a deep persistent problem for all our regions. The exceptions were the south coast, parts of the north coast, the southern Rockies, and southern Kootenays, where a rain event in late-December formed a thick crust that capped the snowpack in those areas. That day, Senior Forecaster Mike Conlan issued his blog, “The Persisting Problem,” which contained our first map outlining the areas where the problem was most prominent. We later refined that map for a subsequent blog, as the extent of the conditions became apparent (Fig. 2). The first fatal avalanche incident of the season occurred on January 9, shortly after it was published. As part of the media response, many of the concepts presented in this blog were incorporated into media pieces and this formed the foundation of much of our messaging for the rest of January and February.

We saw little change in conditions until February and the snowpack remained shallow with no prominent bridging layers to improve stability. February brought an increase in storms and by the end of the month many parts of the central and northern Interior were returning to average snowpack depths. In regions with deeper snowpacks, like the Monashees, Cariboos, and Northern Rockies, avalanche activity on the deep persistent layer tapered. Despite this, concern remained for thin snowpack areas such as windswept alpine slopes (Fig. 3). Another shift in messaging was required and we now pivoted our approach to issue warnings with a more focused emphasis on terrain selection. In regions with thinner snowpacks, like the Purcells, we remained concerned about snowpack stability in more widespread terrain and continued to issue broader warnings in our bulletins.

MEDIA ATTENTION

Fuelled by a series of fatal avalanche accidents, high-profile near-misses, and continued strong messaging by us and other safety organizations, the first two months of 2023 brought an unprecedented amount of media attention. This heightened media interest provided us with a platform to amplify our messaging and effectively reach a broader audience, including those without avalanche training or experience. It served as a valuable tool for conveying our concerns and educating the public on the dangers associated with an unusual season.

Avalanche Canada was featured in more than 13,000 news and media pieces, a rise from roughly 5,500 the winter before. At its busiest time, the forecasting team was conducting multiple interviews daily and the communications team was triaging many more requests. We recognized the importance of maintaining a balance between ensuring effective media coverage and avoiding overexposure. Our focus during this time was on delivering critical information about conditions, promoting avalanche awareness, and emphasizing the importance of caution.

MODERATE OR CONSIDERABLE?

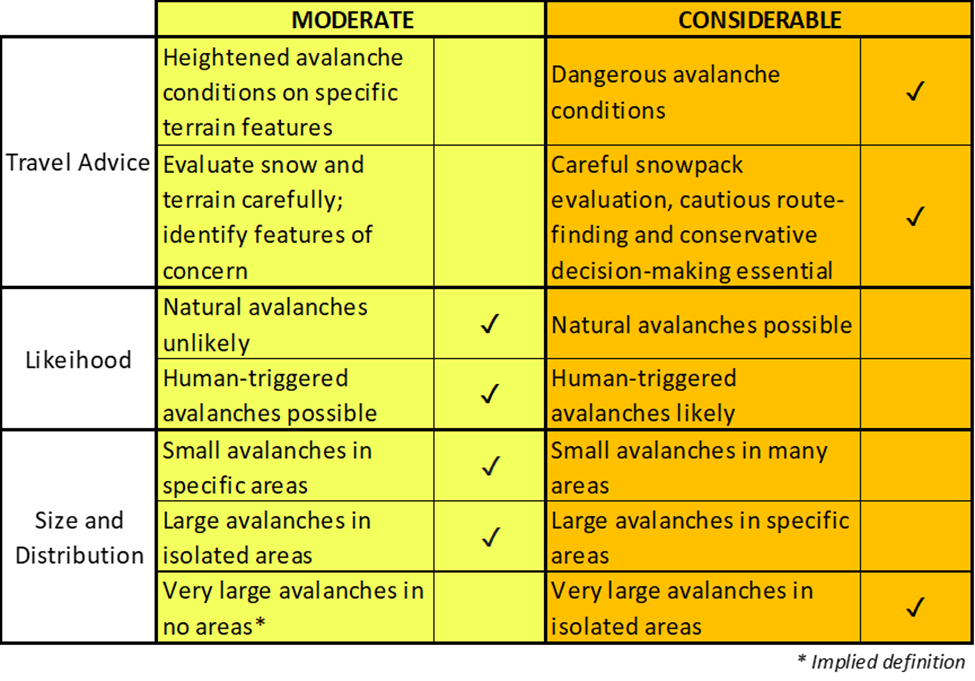

Describing avalanche danger in a period of extended elevated concerns over public safety also introduced another discussion topic to our forecast team: the use of moderate vs. considerable danger ratings in the context of the deep persistent problem. These discussions prompted us to closely examine the definitions of the danger ratings and analyze their individual components within our department. This process helped us identify which elements carried the most significance in the given situation, making it easier to assign a danger rating for a low-probability/high-consequence scenario like the deep persistent problem (Fig. 4).

Early in these discussions, I became aware of my personal bias when applying the danger ratings. I tended to lean heavily on the likelihood section of the rating. For instance, when forecasting for direct action problems like storm slabs, I leaned towards assigning a moderate rating if natural avalanches were unlikely. Conversely, if natural avalanches were possible, my bias would lean towards considerable. However, this

is only one aspect of the definition and with a deep persistent problem, other components should hold as much or more importance. We also

deliberated on the distribution section and debated whether the expectation of very large avalanches in isolated areas should automatically shift the rating to considerable, even if small avalanches were not expected in many areas.

One of the most difficult aspects of the problem during January and February was specifying where exactly the problem existed in the terrain. In the main danger definition, where considerable says “dangerous avalanche conditions” and moderate says “heightened avalanche conditions on specific terrain features,” we found ourselves leaning towards “dangerous avalanche conditions” as the primary focus of our messaging. It was difficult to define the specific terrain features where the deep persistent problem existed in a way that was useful for the public. Roger Atkins’ presentation at the Spring Conference explored part of the challenge related to certainty and where the problem existed. His presentation helped me personally reflect further on how I resolve disparities related to problem distribution, both within the terrain and at a regional level, and how we resolve our uncertainty when making decisions.

Senior Forecaster Simon Horton also provided insights on the problem by saying, “While it doesn’t necessarily fit into the Conceptual Model of Avalanche Hazard or danger rating definitions, I felt a strong intuitive sense that ‘dangerous conditions’ described the approach needed to travel safely in the backcountry better than ‘heightened.’”

REDUCING THE DANGER RATINGS

Only once we had a deeper snowpack at the end of February, with a more robust and bridging midpack, did we feel comfortable lowering the danger ratings to moderate. This decision was based on a decrease in avalanche activity on the deep persistent layer and a clearer understanding of the problem’s distribution. This allowed us to be more specific in our warnings regarding where the deep persistent layer

existed. The exception remained the shallower snowpack regions, such as the Purcells, where the problem remained more widespread and the danger ratings remained at considerable for a much longer period.

Spending so much time thinking about the definitions of danger ratings proved valuable during the season and provided me with a fresh perspective on how we rate danger for various avalanche problems. As forecasters, we carefully consider the rating often, but rarely do we have such an extended period where the danger could reasonably be described by multiple ratings. Since the definitions of danger ratings rarely align perfectly with every element of the avalanche danger, we must assess the significance we assign to each of the individual components and how this fits into our wider public messaging strategy. It is a worthwhile exercise to consider each of the components individually, reflect on how much weight you are putting on each part, and appraise how that may change related to the avalanche problem at hand.

HOW LONG SHOULD THE PROBLEM LAST?

The next important topic of discussion became the ongoing presence of the deep persistent problem in our bulletins once avalanche activity on the layer began to taper off in March. Typically, when dealing with a low-probability/high-consequence problem, our strategy has been to remove the problem from the bulletin during periods of low likelihood and reintroduce it when we expect it to re-emerge. This approach aims to minimize message fatigue for the public and highlight the problem when we expect it to be more severe. However, with this season’s deep persistent problem, some of the forecast team felt uneasy about removing it from the bulletin for several reasons.

Most professional operations consistently included the problem in InfoEx throughout the entire season, and many of their likelihoods were above unlikely throughout March. We monitored this closely using custom InfoEx reports to assess the problem at a regional scale. Many of the hazard ratings in InfoEx also came with caveats and the terrain-travel section regularly mentioned avoiding specific types of terrain. Additionally, many guiding operations reported keeping pieces of their terrain closed for the entire season due to concerns about the deep persistent problem. If professionals remained concerned about the problem throughout the season, shouldn’t we also keep it at the forefront for recreationists, even on days when the likelihood was reduced?

Given the nature of the information being supplied by professional operations and the complexities of distilling this information for public understanding, we decided to leave the problem in the bulletin and adjust the likelihood appropriately. In the later part of the season, there were many days when the problem was characterized as unlikely, yet it remained in the bulletin with messaging reminding users that the problem still existed. It is crucial to remember not all our users are seasoned in the backcountry, and we cannot expect that they have built up a mental picture of conditions as the winter progresses. We also cannot take for granted that they have context for conditions over the previous weeks or months in which to frame the forecast. Decision-support tools like the Avaluator are valuable to many recreationists and rely on the problems section of the forecast. Having the deep persistent problem remain highlighted as an avalanche problem instead of only mentioning it in the details section ensured it could be factored into the decision-making process of the average backcountry user.

As we moved through the season, we often wondered whether we were tending too far towards a conservative approach, being repetitive, or even heavy-handed. But upon balancing these concerns against the information we had and our goal of fostering public avalanche safety, this abundance of caution felt like the best approach.

IN SUMMARY

We all wanted the deep persistent problem to end. I even heard many professionals utter hopes for a high elevation rain event in the middle of winter to alleviate the situation. The rain never came and the snowpack remained complicated for the entire season in the affected areas.

Despite these ongoing challenges, this season still felt like a success in many respects.

Although the total number of avalanche fatalities exceeded the average—something we never like to see—it is noteworthy that the number of recreational fatalities was near average. In a year where the snowpack was challenging from start to finish and accidents seemed to trend towards very large avalanches with multiple involvements, this indicates our efforts were not in vain.

We must credit backcountry users for heeding the warnings and adjusting their mindset. It’s not always easy to keep it conservative for the entire season, especially when the monotony of making conservative choices must have felt at odds with less obvious signs of instability. Without strong messaging, constant media attention, and buy-in from the backcountry community, it could have been a very different outcome. The lessons learned this year will undoubtedly serve to make us better forecasters and help us in our drive to constantly improve public avalanche safety. But we could all probably settle for a simpler season this coming winter.

(1)

- Cam Campbell and Matt Macdonald, 2010. A Recipe For Widespread Persistent Deep Slab Avalanche Characteristics in Western

Canada. Canadian Avalanche Association, Journal Volume 94, Fall 2010. ↩︎