By Alex Cooper

Wren McElroy has spent over 30 years in the avalanche industry, holding a variety of roles throughout her career, including multiple leadership positions. Currently, she is entering her third year as the District Supervisor of the North Cascades Avalanche Program for the B.C. Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure.

At the 2024 Spring Conference, Wren presented alongside Sydney Badger, a Registered Clinical Counsellor, about the mental health program she implemented in her program last winter. In late-July, I interviewed her over video about her journey to that point.

(Note: this transcript has been condensed for space and edited for clarity. Watch the video below for the full interview.)

Alex Cooper: You’ve been in the avalanche industry 30 years, starting as a ski patroller. I wanted to talk about the mental health piece when you started your career, and how you learned to manage mental health over time.

Wren McElroy: When I first started, there wasn’t really any talk about mental health. I was fortunate to work with a solid group of people at Whitewater. We were a very small team, and we spent a lot of time working hard, but then playing hard. At the start and finish of every year, we would do a ski traverse together. Doing things like that, that sense of community, helped foster a team you trusted and supported.

At the same time, we didn’t talk about mental health. There was a lot of colleagues I watched go through scenarios where there might be a fatality or recovery, and there was no real talk or no debrief, other than go to the bar and drink a bottle. That was it. Then things started to surface years later. The team I worked with, we naturally would debrief things, but we never got in too deep in terms of feelings or emotions or ongoing impacts of that stress.

When did your mindset start to change on this topic, become something you wanted to address more directly?

With the various positions I’ve held, different leadership roles, different high-consequence, high-pressure situations I’ve worked in, it’s just been a gradual build up of experiences. The first fatality/recovery I ever dealt with was a very close friend of mine at the ski hill. He was skiing alone outside the boundary and went into a tree well, hit his head, and we weren’t able to find him until the next day. Like many in this industry, I’ve dealt with a lot of loss. As we went into these scenarios, you put your head down, get the job done, and put your emotions to the side and carried on. That’s the job we’re trained for and that’s how we do it. As time has gone on and those experiences built, you realize maybe there are situations that could have been dealt with better.

You started with the North Cascades program, as the District Supervisor in fall 2022. First, can you talk about some of the pressures you face with the MoTI program that can lead to stress buildup and mental health challenges.

With highways, the big thing is it’s 24/7. It’s not like at the ski hill where at 4 p.m., the lifts are shut and everyone goes home, and you don’t have to worry about any exposure overnight.

With the transportation corridors, there’s always people on those highways, so you never really switch off. I relate it to wildfire firefighting. I used to be an initial attack firefighter, and you give yourself over for the season. We do that with highways. You never know when the storms will happen. We run with pretty small teams. When it’s a big storm cycle, it’s all hands on deck. There is no rest or no sleep—you just get it done. We have other programs and we have Senior Avalanche Officers that can come help, but you have to be on all the time.

When you started in this role, what made you want to make sure mental health was built into the program and the operation?

I think that goes farther back. A couple of years ago, I experienced my first post traumatic (reaction). It was 24 years after dealing with a big accident up at the Silver Spray in Kokanee (Glacier Provincial Park).

A couple years ago, in amongst my industry work, having dealt with some very big avalanches, and then a couple notable avalanches around Whitewater, I was cat-skiing and it was the anniversary of the Silver Spray accident. The conditions were prime for an avalanche cycle and things came flooding back to me. I hadn’t actually cried about this incident in 24 years. I had worked on the recovery. There were some close friends in there. In fact, two of them lived in town, one of which I had climbed Mount Logan with the spring before. We lived very parallel lives in terms of our work and our play. It easily could have been me as it was her.

I think I was 24 when I worked on that accident. It was quite mind-blowing to have these images come back, have some tears about it, and even step back from skiing that day. That was very eye-opening. What happened in that time? Could I have done things better? I think it was just survival mode. That was such a big incident that when some of the debriefs happened, I had to disconnect and go to memorials to connect to the human side of that rescue as well.

The second part of that answer would be I started to recognize how I was behaving in high-stress situations and with fatigue, and being pushed to my limits. I really wanted to behave better. I’ve done some things I haven’t been proud of, especially as a leader.

In the bigger picture, I want to provide a better experience for myself so it’s sustainable for me and my team. Now I’m in a role where I provide mentorship to new employees, I hope to minimize—or at least help people cope—if they experience stressful situations so the impact of those stress injuries is lessened.

Going into how you developed the program. You worked with Sydney Badger on this. How did you connect with her and why did you want to talk to her?

I saw her presentation at the spring 2023 CAA meetings and I thought it was very interesting, but I was so new in my role, I didn’t have the capacity to delve into it. Then, at ISSW in Bend, I was very impressed with all the work the Americans were doing. There were so many different options that were presented, I didn’t just have a simple take home.

Then the (fall 2023) CPD sessions came out. I signed up for Sydney’s talk and it totally resonated with me. Because she was local in B.C., I thought, “This is somebody I can connect to.” I asked if she would be interested in talking to us at our pre-season staff training to see if there’s something we can implement. That was the beginning of that relationship.

What were some of the things you did, or you put in place, after working with Sydney?

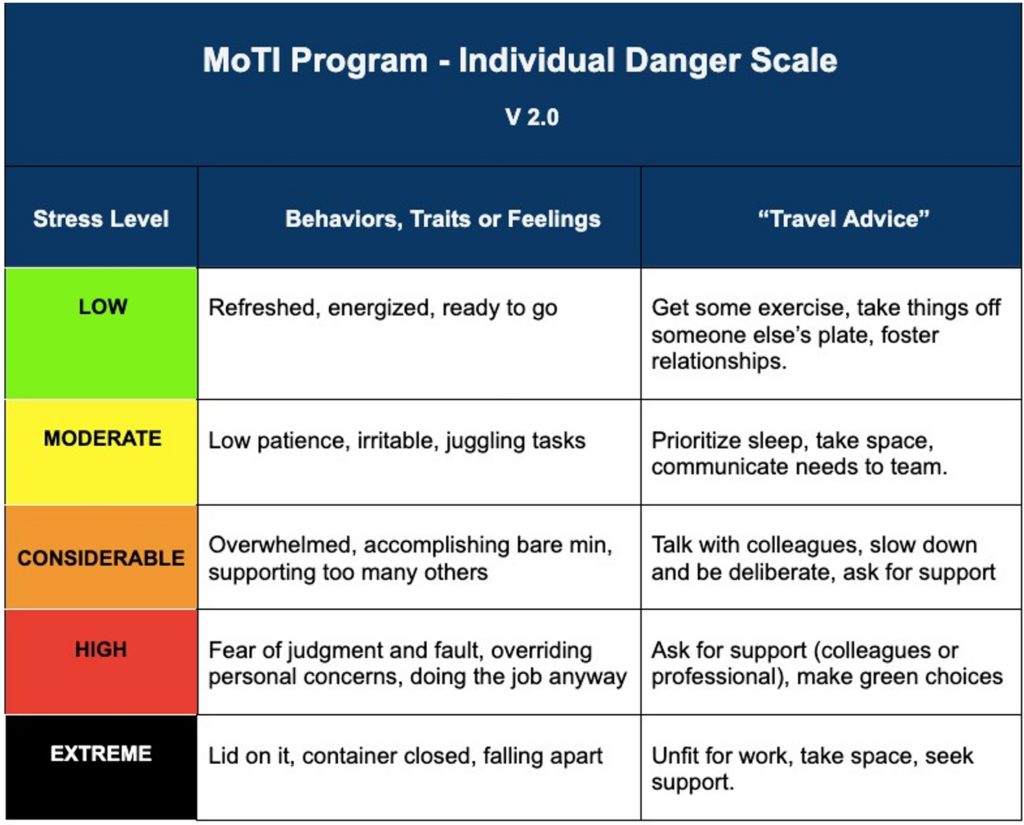

It’s a hard thing to implement. We did a team session with her with three highway programs. She ran us through some exercises and some visualizations, and then we talked about different strategies. From the work we saw in the States, how they put the stress continuum (Fig. 1) into the danger scale, that seemed to really make sense to us. It’s a very familiar format, so it’s easy to relate to. We work in a very specific operation, so we brainstormed and filled out those columns as a team (Fig. 2).

One of the really important things that came out of that was the Do’s and Don’ts (Fig. 3). Recognizing we’re not professionals, we’re not clinical counselors, we’re not psychologists. When we’re trying to support our team members, you have somebody that’s into that yellow, or the orange, or even going into the red—how do we support them? She helped us create some really good guidance to support or help encourage if somebody needed professional help. Even just day-to-day things like, “What can I do to support you?” as opposed to say, giving somebody advice.

Then we got into our seasonal operation, and it was hard to figure out how we put this into the workflow. How do we adapt this? I wouldn’t say we got it perfect and have an actual format or recipe. It was very much a work in progress. And then, as the spring came up, the team I was working with last winter was great, we had some really good sessions.

For those that are familiar with the stress continuum and the colours, that expectation we’re always supposed to be in the green, well, that’s not realistic. Sydney allowed acceptance of being in the different states. We do need to be able to mobilize in the yellow, and we might even be in the orange, but that’s OK. We can operate in those states, and we do it often, but having permission to operate in those states, we used that to calibrate and come in and out of them.

One of the things Sydney talked about at the Spring Conference was going into survival mode, where you’re just trying to get through. Survival mode happens, but if you get stuck, that’s when you can see problems. You eventually go into what she called shutdown mode, where you can start engaging in some destructive habits. What are some tactics you implemented to prevent people from going into that extended survival state or even into shutdown mode?

One of the exercises she did with us that was really helpful was there was a visualization where you picture a place you felt safe, you felt secure, you felt supported. For one person that might be in the forest on the top of the mountain. For me, hanging out with my big fluffy dog brings me a lot of happiness.

She would talk you through this scenario and actually have you think about what does the sky look like, or what are the smells, or what are the noises you hear? She encouraged you to have a space that didn’t involve people, because people are complicated, as she says. Having

something like that, when you’re in those heightened states, knowing you have a safe place to go to, even if it’s momentarily, was really helpful.

You talked about giving people time where they can switch off, not be on-call, and turn off notifications. How helpful did you find doing that?

I think that’s super important. Like I said, we’re small teams, and when it’s on, it’s on. When you have quieter times, being able to provide some flexibility. If my counterpart is on tonight, I’m going to turn my notifications off. If stuff goes sideways, he can phone me. Also, flexibility in the workday. We know we’re going into night shifts, so sending people home during the day to take a nap. Because it’s so demanding when we’re on, having that flexibility is important.

You mentioned the adoption of the danger scale into the stress continuum by the Responder Alliance in the United States. What did you like about using that? And how did you use it in your program?

It’s just because we’re so familiar with it. In the one we did, we put travel advice so when things are happening there’s some travel advice you can do, and it correlated to the levels of where you might be. If you were in the green, or if you’re in the yellow, these are some of the things you can do, or things we can support. Sometimes I found you can see it in other people more than in yourself. I might have a worker who’s in the yellow, into the orange, but they’re so in it, they can’t see it. What are the things we can do to provide support for them? How do you think things went last winter doing this? What did you learn?

One of the biggest things I learned is just about my own self-awareness. Recognizing I’m not in a great state today for whatever reasons and that I need to keep myself in check. My goal is to make better decisions in these high-risk environments, so, providing that framework for myself, and being able to help create that environment for my team so they feel safe, they feel supported, they feel encouraged. We talked about taking breaks and time off, but also keeping morale high. So, the importance of having interesting projects, having things that engage people’s minds.

A few of the things I learned is clearly communicating about hazard and risk is an art. Not taking things personally—sticking to the facts. I have 365 kilometres of road I now manage. Two of the highways, the Coquihalla and Highway 1, have contractor and Ministry boundaries, so there are a lot of different people I have to communicate with. Keeping the communications clear helps keep it all in check.

You have to balance managing your own mental health, you’ve got your team’s mental health, and then you also have the operational challenges where you have to get the highway open. How did you balance those different challenges?

For myself, I’m really trying to work with the concept of wellness. So, recognizing when I don’t get enough sleep. Sure, when we’re in an extended storm period, you’re not going to sleep and you’ve got to make that up, but when you’re not in that period, trying to keep that battery bank full. Getting healthy exercise, getting movement in. Sometimes we’ll take a team meeting and instead of sitting in chairs talking to each other, we might go walk around the block.

Last winter, I didn’t drink for close to three months and that was incredibly good for my wellness. I had a ton of energy, I felt great, I felt I could communicate better. Not that I drank lots, but just culturally, that’s been a part of our thing. For myself, taking time to connect with my family when I can, and trying to take good care of my mind and my body. For my team, we talked about allowing breaks and having some flexibility, keeping the morale high, keeping them interested.

Operationally, not taking things personally, sticking to the facts. Keeping emotions in check, especially when fatigued. Sticking to those facts is helpful with any kind of communication.

One thing you mentioned at the Spring Conference is you had to learn how to make yourself vulnerable. I expect there might be a lot of people in the industry who face that similar challenge of being vulnerable, and just letting people know when they’re not doing well. Do you have any advice you could share?

I think being honest with yourself and understanding what your limitations are and where you’re at is really important. It might be that I didn’t sleep well, or something’s going on in my personal life, or I’ve had a conflict with a co-worker. Being able to say, “Hey, I’m in the yellow today, but I don’t want to talk about it.” I realized, it’s easy for me to ask my co-workers to tell me; I’m the supervisor. But realizing I didn’t want to, because I’m the leader, I have high expectations of myself that I’m always on and ready to go. That was a key thing that hopefully allowed everyone to relax a little bit, that it’s OK to be in a vulnerable state. It doesn’t mean you can’t do your job, but if we’re aware of it, we can take care of each other better.

I think early on in my career, I had this fear of not being good enough. I’d spent most of my career as the only female and so there was always that added pressure I have to be tough and I’ve got a thick skin, and I prided myself on that. I think now I’m later in life and it’s OK, I can be vulnerable, and just the strength that comes out of that. I think there’s a lot to be said for that in terms of being open with your team.

What advice do you have for other operations?

We aren’t professionals in this. There are lots of resources, there are courses. I recognized I didn’t have those skills, nor did I have the capacity to orchestrate the whole thing. Working with somebody who’s professionally trained is really important. If you’re really trying to set up something that has structure, there are simpler things you can do. There are resources from the Responder Alliance you can incorporate. I wanted to provide a bit more structure and I wanted to continue learning about it as well.

Is there anything we missed or anything you want to add?

You asked how to manage the stress personally, operationally. I realized a bunch of years ago, my whole life was around skiing. At some point when I was running the snow safety program for Whitewater, I realized I started dreading winter. I talked to an old friend and colleague, Jason Rempel from Stellar Heliskiing. “What is this? I love skiing, this is my passion, but I really like summer. I’m anchoring on summer.” He said, “Well yeah, in the summer you’re not responsible for anybody’s life.” It dawned on me the importance of recharging my batteries in the summer. Now I do have a year-round job, but I don’t have avalanches in the summer, so there’s way less stress. I’m able to take more time off. For me, I charge the solar panels in the summer and take care of myself, knowing I’m setting myself up for success physically, mentally, so I’m ready to go at it again.