By Julie McBride

Note: This article initially appeared in The Avalanche Journal, Volume 113, Fall 2016

FOR MARMOT BASIN, Friday, January 29, 2016 marked the end of a nearly two-month drought. Although November blessed us with a dump of snow during our opening week, December and January had forsaken us. Our last appreciable snowfall had been seven weeks prior on December 9. The arrival of the much anticipated storm was also the harbinger of a human-triggered avalanche cycle from the Icefields Parkway to McBride, BC. A total of five separate events involving avalanche professionals as well as recreationists all occurred within a 200km radius of Marmot Basin. It was a busy day in the avalanche world near Jasper, one that would ultimately cast a sombre shadow over our operation for the remainder of the season.

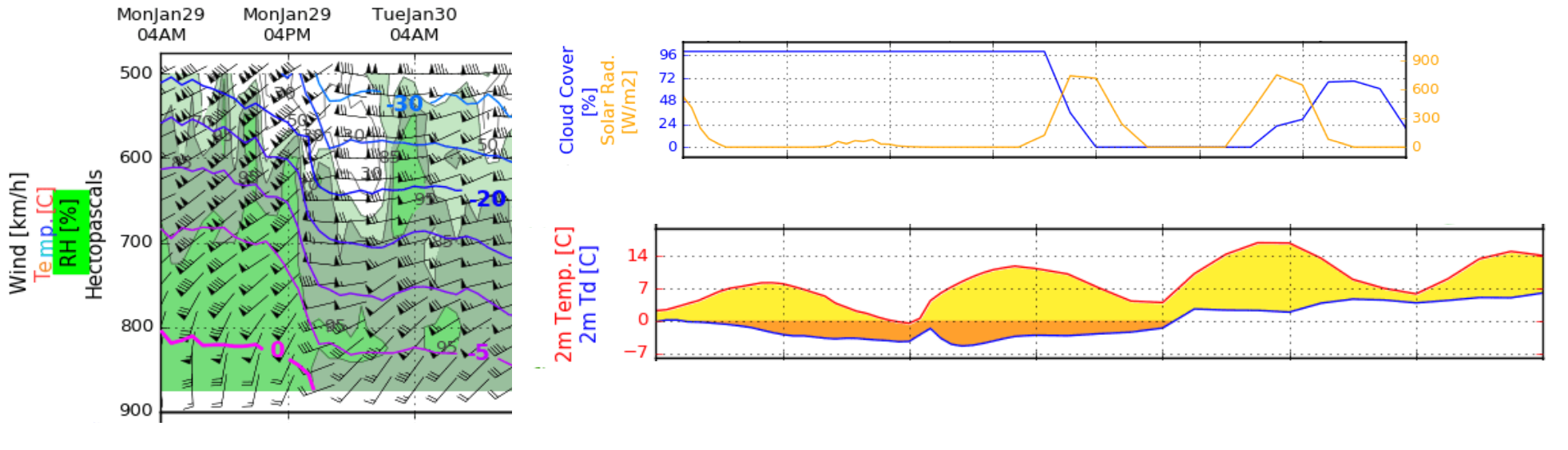

During the drought, temperatures had ranged from just below –20°C to just above freezing with a week of sustained cold. With less than 90cm of snow on the ground, Marmot’s was a textbook continental snowpack—shallow and weak, facets throughout, sitting on a base of depth hoar. Although the “storm” delivered only 8cm of snowfall in 24 hours, it was accompanied by moderate to extreme southerly winds, that formed a new storm slab. Friday, January 29 was our first avalanche control morning in weeks.

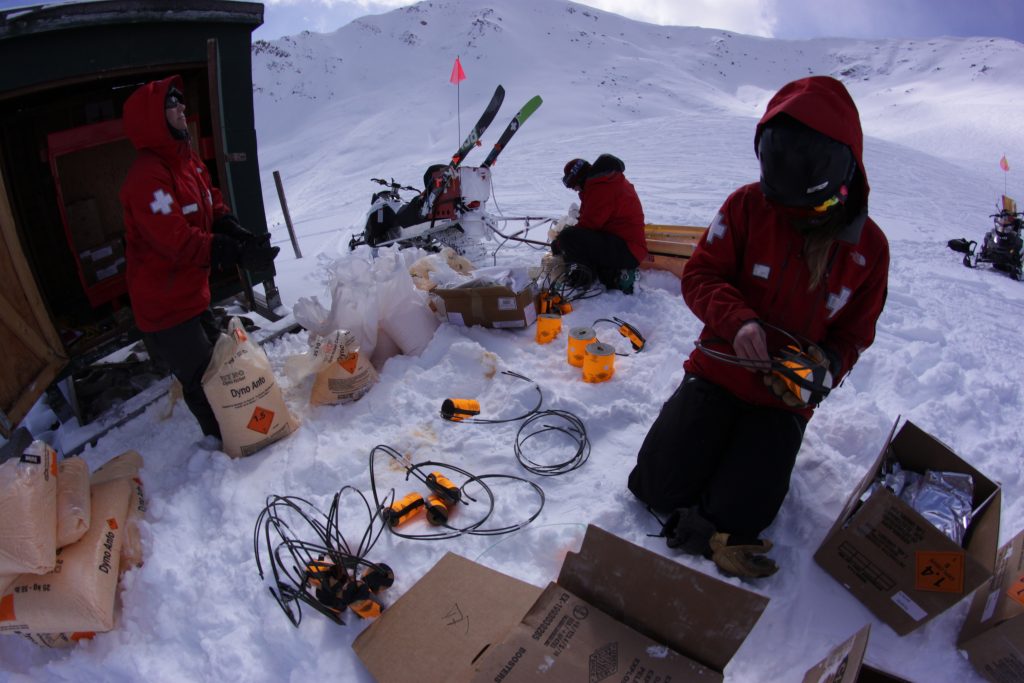

As the forecaster that morning, my first priority was an Avalauncher shoot that produced results from size 1 to 2.5, with the larger releases initiating in the storm slab and then stepping down to a layer of facets and depth hoar, 50-70cm down. Satisfied with these results, I turned my attention to Charlie’s Bowl.

A northeast to southeast-facing alpine bowl with a series of steep, rocky chutes below its entrance adjacent to the Knob area, Charlie’s Bowl had not yet opened for the season. In mid-November, Chutes 5 through 7 had released to ground during a natural cycle. A week later, Chutes 5 and 6 failed to ground with explosive control work. With more explosives in December, Chutes 6 to 9 released to ground for a third time. By mid-January, ski cuts produced only small results in isolated pockets of thin wind slab. We began ski compacting and waited for more snow to open Charlie’s to public. Late in the afternoon on Thursday, January 28, with over 100 sets of tracks around me, I stood at the top of the Chutes, snow and wind obliterating my visibility, hopeful that we might be getting close.

The first two one-kilogram hand charges in Charlie’s Bowl on the morning of the 29th produced no results. Two more 1kg charges, deployed simultaneously at either end of a broad apron above the Chutes, also failed to produce a result. With no more explosives, I proceeded to ski cut from my position at the top of Chute 8. Once I was clear, my partner, one of our avalanche technicians, did the same in Chute 5. While ski cutting we both noted a 10-15cm thick, 1F slab that was penetrable on skis, but no signs of fracture propagation or releases other than small fist-sized slab cookies. Then I decided: the avalanche tech would take two patrollers and continue ski cutting in Charlie’s to break up the slab, while I moved on to another area with a third patroller.

Minutes after we’d parted ways, I got a call over the radio from one of the two patrollers in the Chutes: “We’ve had a deployment; he’s on top…” Oh shit. The tech had gone for a ride. Then a second call from the tech: “I’m ok.” Thank God.

As the tech skied into Chute 6, a small pocket of wind slab had propagated into the rocks above him and then stepped down to ground. With no escape, he’d deployed his air bag and was swept by a size 2 for nearly 200m to the flats at the base of the chutes. Spotting from above, his partners reported that he’d been on top of the slide the entire time and that when it came to a stop, he appeared to be sitting upright in the debris, his legs buried to the hip. He had lost both skis and one pole but was able to selfextricate. By the time his partners had made their way to him, he was free and clear of the runout zone, a bit shaken but understandably so. Although he had tweaked his lower back while twisting to release from his skis, he had somehow managed to otherwise emerge physically unscathed from a rather nasty ride through some very thin, bony terrain.

No stranger to ski cutting, it was the tech’s third involvement during his seven-year tenure at Marmot. His propensity for triggering avalanches was already well established. At 6’8” and 260lbs, he has been known to trigger slopes where even large explosives have failed. His skis sink deep into the snowpack and he has a knack for finding the sweet spot.

In addition to his formidable stature and reputation, his pursuits outside of work invoke similar images of unbreakable nerve and strength: base jumping, parachuting and backcountry sledding. This is someone who had been hired as an avalanche tech not only for his knowledge and experience, but also for his ability to remain stolid and clear-headed in stressful situations. It came as no surprise that after debriefing with the control team he was ready to get back on the horse, so to speak.

Back at the top of Chute 6, he gladly volunteered to place a 6.75kg sack of explosives into the hangfire. The shot cleaned out what was left, taking Chute 7 to ground along with it and releasing the thin storm slab in Chutes 8 and 9, which ran over top of the ski cuts in Chute 8 from a few hours earlier.

That afternoon, details of other larger events to the south and to the west of Marmot began to circulate on the news and within industry channels. A Visitor Safety Officer from Jasper National Park had been involved in a skier-accidental size 3 that deposited nearly two metres of debris on the Icefields Parkway near Parker Ridge, closing the highway. And at least 15 snowmobilers from three separate groups were involved in a size 3 machine accidental near McBride that resulted in the deaths of five snowmobilers.

Amidst these rumours and half reports I went home that night and contemplated the decisions I had made that day: where I had failed, what I could have done differently, what I had learned, what I would do differently now, what I would do in the future. My head reeled from the cerebral merry-go-round.

As avalanche professionals we spend a great deal of time talking about avalanche problems and avalanche hazard, and how things like variability, uncertainty and confidence play into our analysis of what the problem or hazard actually is. We also talk about human factors: nebulous sub-conscious phenomena that can sometimes lead us to miss or misinterpret pieces of information, or bias our intuition and instincts. Even though we employ various tools, decision aids, methods and procedures to avoid mistakes of both the analytical and the human kind, sometimes unexpected or unlikely things happen. Sometimes we get caught in slides. That is just the nature of snow on steep slopes. And it is why we also practice and teach avalanche rescue skills. There is always uncertainty and sometimes we get it wrong.

While I knew that my decision to continue ski cutting that morning had turned out to be a bad one, the reality is that the possibility of going for a ride exists every time I or someone else ski cuts a slope. Still I couldn’t help feeling that I’d let the team down, in particular the tech who had been the victim of my decision. An element of complacency had crept in during the drought. Having seen little change from day to day for seven weeks, I’d underestimated the effect of a little bit of new snow and some wind on our deep persistent layers and what a light trigger in the right spot could do, even in worked terrain. My confidence was rattled. Our snowpack was weak and unpredictable, and the head forecaster and I resolved to punctuate future control missions with larger explosives.

In the week that followed, it was obvious that the tech who’d been involved was clearly struggling to deal with how he had been affected. He was having trouble sleeping, he was having nightmares, his hands trembled, his head just wasn’t in the game and the pain in his lower back had worsened. We sent him to a doctor, a physiotherapist and a critical incident stress counsellor. We filed a workers’ compensation claim and he was placed on light duties.

The physiotherapy sessions continued, the counselling sessions continued. Weeks passed, then months. His mood and progress seemed to ebb and flow. Every day was a different day, each with possibly a different challenge. He started experiencing panic attacks. He was frustrated. With no manual, tools or methods guiding us in supporting him, we—his supervisors—were frustrated. We talked, we talked with him, we talked with our managers, we talked with WCB, then we talked some more. I suggested that perhaps some time completely away from the work environment would help. He opposed; he felt that his anxiety was something he had to face head on and that stress leave would be counterproductive to learning how to overcome it. I was skeptical but conceded. After all, I was no expert and I admired his dogged determination. He was doing everything right. And while he struggled, the rest of us carried on, not for lack of compassion but for lack of other options.

The season continued much as it had begun, with little snowfall and low confidence in our snowpack. We opened most of our avalanche terrain eventually. Large and numerous explosives continued to produce large avalanches running on deep persistent weaknesses. We were cautious and conservative. Temperatures remained above freezing throughout most of April. An impressive iso-cycle ripped out moguled runs down to the basal depth hoar; our suspicions were vindicated. As we packed up our gear on our final day of the season, the tech was clearly still struggling. I watched the panic wash over his face when someone deployed an avalanche airbag for summer storage, triggering a flashback and the anguish of his trauma. My heart broke. It’s the last day, what happens now?

The tech has since been diagnosed with an adjustment disorder. Over the summer worked with a team of professionals (a psychologist, occupational therapist and a physio/personal trainer) overseen by a specialist in traumatic psychological injuries. It is still a long road ahead but one that he is facing with courage and optimism. He is Hercules to me, and like all parables his trials hold a lesson for us.

When avalanche professionals talk about human factors, we need to talk not only about what goes on in the subconscious prior to our decision of whether or not to ski into a slope, but also potential consequences of that decision at the psychological level as well. Although we find it easy to casually discuss the physical consequences of an avalanche with euphemisms such as “raked through the trees” or “cheese-grated over the rocks,” we rarely discuss how the same event might affect one’s mental health. Or if we do, it is often in hushed voices, behind closed doors: “Why can’t she just deal with it?”

That is because psychological or mental health issues of any kind have a stigma in society in general. It’s not polite to talk about the elephant in the room or the crazy uncle in the attic, so to speak. And this is precisely the reason why we need to talk about it, because the patroller who goes to a wreck or the tech who goes for a ride or the guide whose guest gets buried might not be able to. They might not even recognize that they’ve suffered a traumatic psychological injury, never mind have the strength to admit it to themselves and ask for help. As their supervisors, we need to build our knowledge and understanding of “mental health first-aid” and have these tools in our proverbial tool-boxes when we start the conversation.