Planting The Big Burn on Hwy 3

By Mark Grist

This article was originally published in The Avalanche Journal, Volume 128, Winter 2021-22.

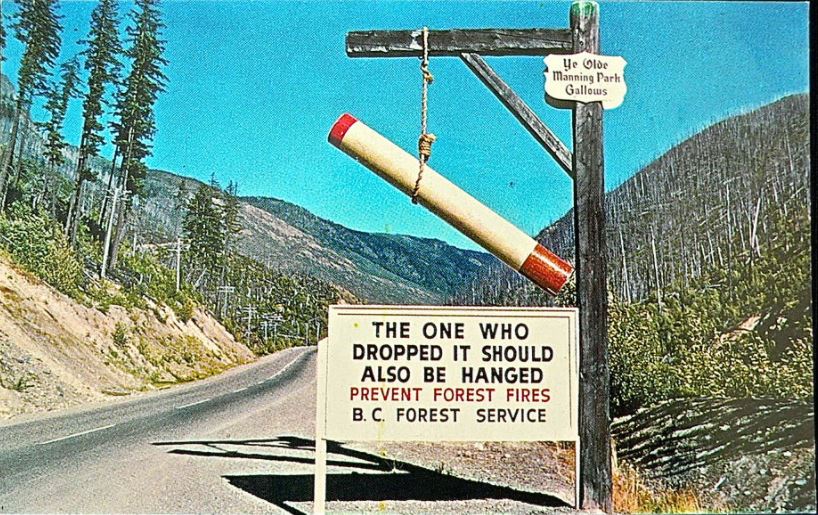

MANY BRITISH COLUMBIANS are familiar with the story of the 1946 ‘Big Burn’ on Hwy 3 and the infamous Manning Park Gallows sign that was erected afterwards. Ben Bradley’s excellent book British Columbia by the Road (1) tells the story of how 2,300 hectares of forest burnt as a result of a campfire left unattended by prospectors, and how the parks branch seized the opportunity to make the memorable roadside sign. What is less well known is how the former Department of Highways undertook an aggressive tree planting program to reforest the burnt out avalanche start zones in the late 1970s.

The project emerged as a legacy of the January 1974 avalanche that claimed seven lives at the North Route Café on Highway 16 west of Terrace, B.C. (2) The provincial government formed the Avalanche Task Force to look at ways to prevent future accidents. The task force submitted its report to government in October 1974 (3). One specific recommendation it made to safeguard highways was the use of reforestation as a “permanent avalanche control measure.”

Requesting assistance from the research division of the Ministry of Forests, the technical aspects of reforestation along Highway 3 were outlined in a 43-page report (4) by legendary BC forester Karel Klinka and RW Mitchell in November of 1976. Avalanche Control with Reforestation – Experimental Project 781.02 was published two months later, in January 1977. The total project cost (in 1977 dollars) was $135,250 or $181,750 (about $550,000 and $750,000 in today’s dollars, respectively) depending on seedling type chosen (5). This budget included 286 hours of helicopter time.

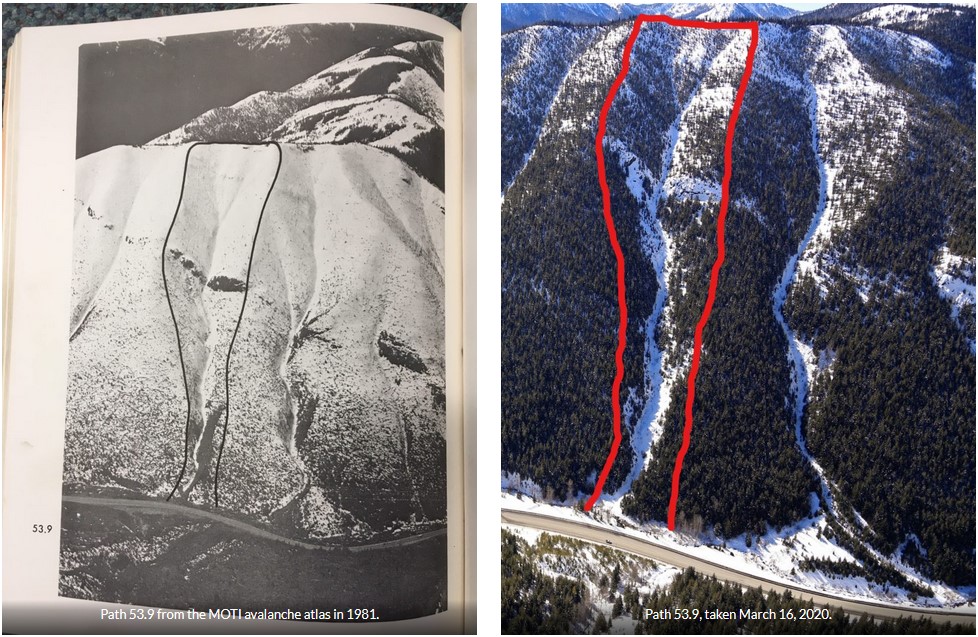

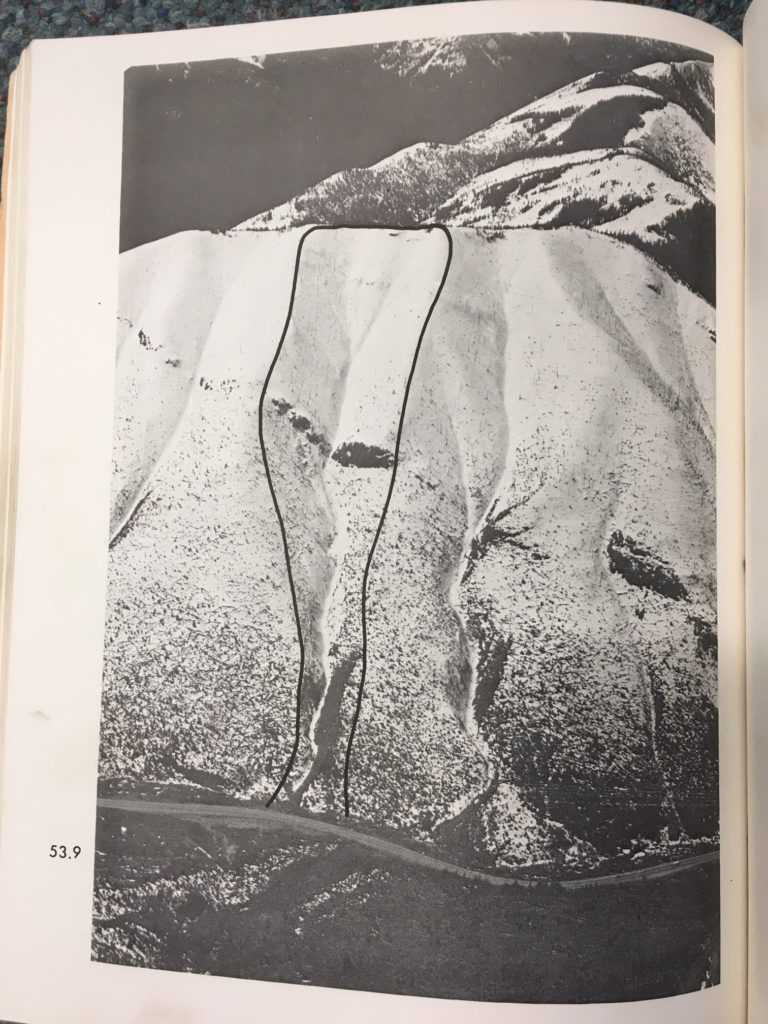

On the ground reconnaissance “to find severe sites, similar to those of the avalanche starting zones, along roads” took place during the fall of 1977. Preliminary field trials of seedling test stock started at two sites in Manning Park in late September of 1978, with 1,977 seedlings planted. Over the next three years, more than 40,000 seedlings were planted in the start zones of highway avalanche paths, including 11,799 trees in the Burn North paths in spring 1981. A mix of species was planted, including Engelmann spruce, Douglas fir, lodgepole pine, and subalpine fir (the best performer on north aspects). Interestingly, receipts from 1979 showed fuel charges at 26 cents per/litre and helicopter time billed at $300 per hour (about $1,060 per hour in 2021 dollars) from Highland Helicopters Ltd. in Vancouver—a similar machine would cost $1,500 per hour today!

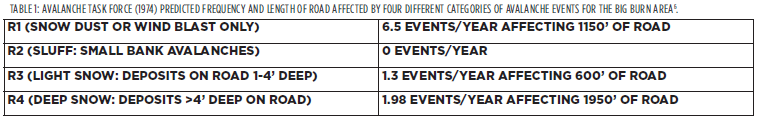

In the Avalanche Task Force–Technical Supplement (6), Allison Pass (Highway 3 between Hope and Manning Park) was rated as a MODERATE Avalanche Hazard Area (index rating between 10-100) back in 1974, noting “the highest avalanche hazard exists in the Burn.” Table 1 below qualifies “the avalanches according to the damage which they can produce to traffic” and predicts their frequency (6). Thanks to reforestation [including 164,000 seedlings planted on lower slopes between 1953 and 1960 (4)], the frequency in all categories has been zero for several years now.

Peter Schaerer authored the technical supplement section for Allison Pass and predicted, “Restoration of the forest would eliminate the avalanches on the south side, and infrequent large avalanches only would be observed on the north side.” Indeed, the trees have held and the last notable avalanche was in 2009, while the last avalanche to affect the road was in 1996.

It remains to be seen whether we have entered a new norm of severe summer wildfire seasons, but we can say that the three worst in British Columbia’s recorded history have all happened in the past five years. After significant wildfires in Waterton National Park, RAAMS simulations by Campbell et al. showed an increase in runout distance near, and measured post-wildfire runout extents increased on Mt Whymper (7). While remote avalanche control systems and passive defense structures are excellent solutions to be implemented on a short timescale, one could make the case for reforestation being the forgotten ‘semi-permanent’ avalanche solution where climate and soils allow, especially considering treelines have been increasing in elevation (8) and will continue to do so if climate trends continue.

REFERENCES:

- Bradley, B. “British Columbia by the Road: Car Culture and the Making of the Modern Landscape” UBC Press, 2017, 324 pages.

- Stethem, C.J. “The Fatal Avalanche at the North Route Café: Subsequent Changes to Avalanche Risk Management for Highways and Occupied Structures in BC.” The Avalanche Journal. Volume 117, Fall 2017, pp 28-30.

- British Columbia Department of Highways, 1974. Avalanche Task Force Report. Government of British Columbia (Godfrey, D. (Chair), Schaerer, P., Tremblay, R., Freer, G., Evans, S.) 33 pages.

- Klinka, K., and Mitchell, R. “Ecosystem Evaluation and Reforestation of Avalanche Sites in Allison Pass.” British Columbia Forest Service Research Division, November 43 pages.

- Pendl, F. “Avalanche Control With Reforestation.” Experimental Project 781.02. British Columbia Forest Service. January 1977.

- “Avalanche Task Force – Technical Supplement”. September 30th, 1974.

- Campbell, C., Gould, B., Thumlert, S. 2019. “Post Wildfire Analysis of Avalanche Hazard.” The Avalanche Journal. Volume 121, Summer 2019, pp 22-25.

- Koch, J., Menounos, B., Clague, J., Osborn, G. 2004. “Environmental change in Garibaldi Provincial Park, Southern Coast Mountains, British Columbia.” Geoscience Canada. 31 (3): pp 127-135.

Mark Grist is an avalanche technician with the BC Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure’s Columbia Avalanche Program. He previously worked for Avalanche Canada (public forecaster), BC Parks (winter backcountry ranger), Cypress Mountain (Nordic ski patrol), and was a resource member with North Shore Rescue for five years.