The Importance of a Critical Incident Stress Management Plan

By Erin Tierney

This article was initially published in The Avalanche Journal, Volume 129, Spring 2022

THE CONVERSATION ABOUT MENTAL HEALTH is a tricky one to start in our industry of mountain professionals. Historically, when it was raised, you were taking a risk. Stoicism, the endurance of pain or hardship without the display of feelings and without complaint, was the dominant mindset. Though stoicism certainly has its place at times, there is also a need for resiliency, which is the ability to draw on personal strengths as well as the support of the community. Developing resiliency creates the awareness to acknowledge and the opportunity to

work through emotions when impacted by an event, especially one that is outside of your day-to-day norm.

Patrollers and dedicated rescue teams aside, we are not first responders. We train extensively for rescue scenarios, but they fall under the category of an abnormal event in our regular duties and, therefore, a wide range of reactions are considered completely normal. The probability of experiencing a traumatic event is almost certain if there is enough exposure, like in the case of a lengthy career. This reality is often acknowledged.

What has been harder to say is that sometimes, after the debrief is over and the world has moved forward, some of those that experienced the event are still grappling with what happened and it doesn’t feel good. The impacts of these exposures on an individual can vary widely—from an experience you are able to acknowledge, and move on from with little after effect; through to an event that stops you in your tracks, shatters your belief system, and leaves you with a constant sense of foreboding.

The ability to recognize, acknowledge, and manage stress after a traumatic incident is a sign of strength and awareness of critical incident stress (CIS). CIS refers to the range of physical and psychological reactions one may experience after an incident. It can, and does, affect anyone regardless of experience, gender, or age; and is a completely normal reaction to an abnormal event.

PSYCHOLOGICAL FIRST AID

Getting psychological first aid for your brain is akin to getting physiotherapy for a physical injury. How many times have you tweaked your back, knee, or shoulder and limped through the healing phase without admitting the injury? How often have you said, “It’s fine,” because it was high season or you just didn’t want to show weakness by admitting something in life can slow you down?

In our industry, whether it’s guiding, patrolling, highways, or industrial work, we play a heady game every day, trying to outmanoeuvre the weather and manipulate the snowpack so we can achieve our professional goals. The challenge is what makes our jobs so fun and exciting, and one of the reasons why we leave family, friends, and a life of normalcy behind every winter. Admitting to gaps in the armour, whether mental or physical, puts us at risk of weakening our identity, our reliability, and our capability. At least that’s where our culture has sat

for a long time.

I’ve told myself all those things indirectly and subconsciously many times over the years, from both sides of the table. I’ve been an operations

manager who called a professional counsellor to run a debriefing after an incident and then expected everyone to jump back into action once that box had been ticked. And I was a guide who experienced a traumatic event and couldn’t “suck it up” and get back out there no matter how strong my will was.

The route to recovery from a psychological injury is not well understood in our industry and to embark on that path as an individual can be a scary proposition. Fortunately, our community is uniting to encourage conversations, get the stories out there, and let those people trying to find their way know that they are not alone.

OUR CIS STORIES

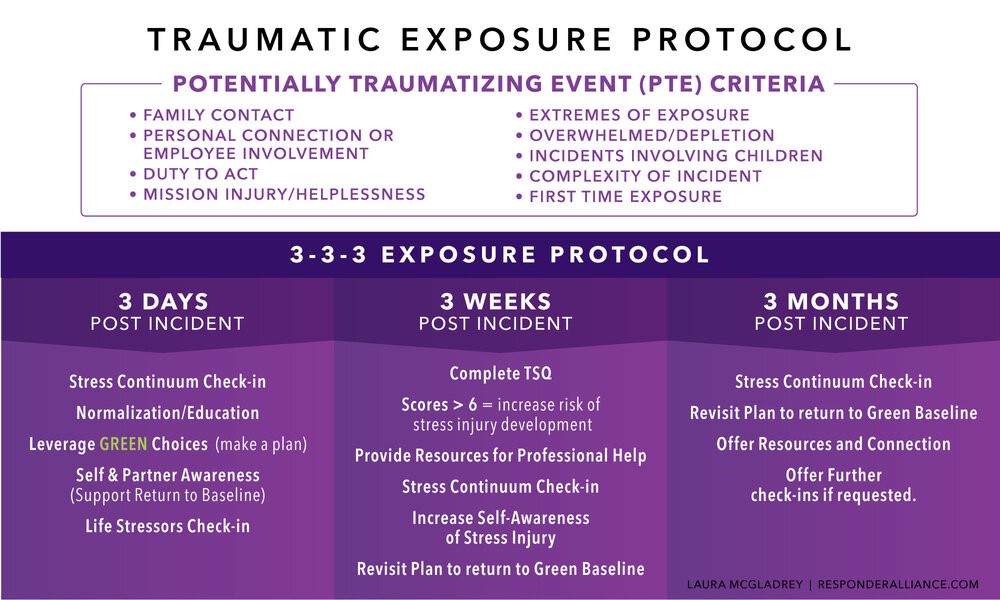

Last year, during the fall CPD sessions, the CAA, CSGA, and ACMG provided focused sessions on mental health education and awareness. As a presenter for the CSGA, I spoke about the value of creating a more proactive and preventative critical incident stress management (CISM) plan. A CISM plan is commonly a reactive plan that centres around responding to the incident rather than trying to get ahead of it before it even happens. The extent of most plans acknowledges that CIS can exist after an incident and offers outside resources to support individuals.

A proactive plan is one that educates the team about stress and how it can manifest its way into your life. The plan emphasizes the importance of staying connected to your community and how to talk to a teammate who is experiencing CIS. The National Institute for Health reports that the number one predictor for how someone will recover from a traumatic event is based on how safe they feel in their relationships. Our teammates are integral relationships in the healing process. Having a community around that is educated about what

someone may be going through is some of the best therapy there is.

I felt nervous sharing my story, wondering how I would be received after admitting I had experienced severe PTSD. In the years prior to my accident, I had witnessed many peers suffer from CIS and PTSD and I now realize I had had no idea how to help them. Until I had lived through it myself, I didn’t truly understand the hurdles one must face on the path to healing. I also realized that a lot of those hurdles could be knocked down with a few simple proactive steps.

Each person’s CIS story and response is unique. Sharing our stories lets people pull pieces out that they can relate to and build their own paths to healing. The other benefit of sharing is that it becomes apparent pretty quickly that these stories aren’t one-off events. The impacts of both accumulated and acute stress are felt widely throughout our community of mountain professionals.

So, how do we create a more proactive CISM plan? Mental health care does not need to be solely associated with negative connotations and illness. We need to create a proactive environment that encourages our community to recognize, acknowledge, and manage the stressors faced in our line of work through education, peer support, and operational procedures. Currently, we operate in a reactive state. We don’t

recognize accumulated stress and, when faced with a traumatic event, we are on our heels, calling a counsellor for support to help get our world back in order and contain the damage.

We have an opportunity to change this reactive approach. Knowing that healing is possible and that these are normal reactions to an abnormal event empower a person and help stop them from withdrawing into a cocoon of isolation. Creating a community of peers that is aware of the range of normal CIS reactions and developing language to support those affected is a lifeline to recovery.

KEY STEPS IN CREATING A PROACTIVE CISM PLAN

Education: Providing educational sessions at staff training on how to recognize, acknowledge, and manage stress creates a common language and a level of understanding in the workplace. It normalizes the fact we operate in a stressful environment and creates a culture that promotes inclusion of these factors in our daily conversations. It also aids in the management and support of an individual or group that has been exposed to a critical incident. It gives your team the language to know what to say, keeps the conversation open, and allows those affected to feel empowered to stay connected to the team and seek additional supports if needed.

Peer support: When a critical incident occurs in an operation, there is no one who can understand what you may be going through better than a teammate. You may or may not want to talk, but having someone that just gets it is so much better than having to explain how your job works before you can get to what really matters. Developing a group of trained peer support people on your team allows for that to happen. It also means you have direct access to a team that can run a defusing session immediately after a critical event and provide opportunities and connections for internal and external support. Investing in this resource demonstrates a dedication to psychological first aid and a proactive and healthy culture.

Operational integration: Whether it is a training event or an actual critical incident, a technical debrief is an entrenched component of the

emergency response plan process. Add a psychological debrief to your workflow, too. After the technical debrief is complete, before everyone disperses, a member of your peer support group can step forward and announce there will be a confidential, psychological

debrief for those directly involved. This process doesn’t have to actually occur after a training session but should still be verbalized so that it becomes part of the operational process. Verbalizing the action means that when a critical incident does occur, the psychological debrief is just the next step and not an awkward call out. It becomes just another step that you take in your procedures.

Critical incident exposure tracking is another tool that aids in awareness and recognition of psychological first aid. It also helps with documentation to aid in receiving outside support through an agency such as WorksafeBC. Creating a simple form where individuals can make note of their exposure to any type of critical incident provides a tool to track potential impacts of a singular event and the accumulation of exposure from multiple events, which can be a harder pattern to identify.

Challenges: Adding more tasks to a long list of operational requirements can seem daunting, add costs, and take up valuable time that always seems to be at a premium. Pre-season training schedules are already bursting and paying employees to be on site when there is no direct revenue gained is always a tightrope walk to find the balance between benefit and return. Staff can be transient. Some operations are quite small, which means a critical incident can affect your whole team and leave you without the use of your peer support team because they need support too.

You would never consider a start to your season without training for the worst case scenario such as avalanches, rope rescues, and first aid. You are being proactive by making sure those skills are sharp should you need to react to a situation gone wrong. Psychological first aid is an extension of any and all incidents. Anyone, regardless of experience, gender, or age can be affected by accumulated or critical incident stress. Having the skills to dig someone out of an avalanche of psychological trauma will always prove to be more successful than having to learn how to turn the transceiver on once they are already buried. Investing in this knowledge will save employee time loss, create connection to the workplace, and produce a resilient workforce.

FUTURE GOALS

We are a community that is connected. It does not require a long conversation to find acquaintances, colleagues, and friends in common. People move between operations and different arms of the avalanche industry. Some operations are tiny. What if we came together as an industry and provided access to education about psychological first aid and resiliency training? A first aid course is required for just about any job out there. How about a psychological first aid course that supports both proactive and reactive response tools? One that educates on how to recognize potential stressors, acknowledges when those stressors are affecting us, and manages those stressors so they don’t build up to the point where our capacity to deal with life is diminished. When things do go wrong, it teaches tactics for how to talk to each other, a common language that offers support and understanding, and pathways to heal, all from within our community.

A course like this, taught by our peers, would mean that if an employee moved to a new spot, the next hire would likely have this training too. It would mean that a small operation could call on its nearest neighbour just as they would if resources were short in any other type of rescue. The neighbour could send its peer support team over to assist in those crucial hours after an incident before a trained counsellor could be called in.

There are a few programs like this in development and my hope is to continue to work with our industry partners towards a common goal of

creating an accessible, affordable course that has us all climbing this mountain together, because, as cliché as it may have become lately, we are truly all in this one together.

About the author

Over the last 24 years as a heli-ski guide, CSGA instructor, and more recently as an avalanche technician, Erin Tierney has been honoured to hear a lot of people’s stories and shared a few of her own, which includes healing from PTSD following a helicopter crash. She is the current President of the CSGA and chair of the Education Committee, and a Professional Member of the CAA, where she sits on the Membership Committee.