The Story of Parks Canada’s Backcountry Avalanche Risk Review

By Grant Statham

This article initially appeared in Volume 131, Winter 2022-23 of The Avalanche Journal.

ON FEBRUARY 1, 2003, A HUGE AVALANCHE in Rogers Pass buried 17 students and teachers on an outdoor education ski touring trip up Connaught Creek. Seven grade 10 students were killed. Twelve days earlier and 30 km to the west, a similarly huge avalanche on the run La Traviata killed seven adults on a guided ski touring trip. That winter, 29 people died in avalanches in Canada, the worst year on record. We all knew this would have implications.

I was 34 and had spent the previous 17 seasons working as a ski patroller, avalanche forecaster, mountain guide, and avalanche consultant. Following the Rogers Pass avalanche, Parks Canada commissioned a review of its whole public avalanche safety program. The Parks Canada Backcountry Avalanche Risk Review returned 36 recommendations. The Province of BC did its own review, as did Strathcona-Tweedsmuir

School. All told, there was 81 different recommendations made by three different independent reviews. I was hired by Parks Canada on a two-year term to implement the recommendations of the Risk Review. I started on Nov. 3, 2003, and walked into the most intense professional experience of my life. I think of it as the day I went inside.

I began with a blank slate—an office in the “Kremlin,” an empty desk, computer, telephone, 9-5 schedule, and plenty of offers to help. Ian Syme helped me find my way and Bill Fisher, the Executive Director of the Mountain Parks, was my boss. I began to make contacts, develop my ideas, and put together a tangible plan for what Parks Canada was going to do.

Those first three months were a blur of false starts, intense media pressure, and an overwhelming new reality for me. I reached out to meet the parents of the Connaught Creek students and share with them my ideas, which marked a turning point in the project. Unknown to me, our CEO Alan Latourelle had done the same thing. Those parents became our allies and, together with my colleagues and closest friends, we developed plans to change the way public avalanche safety was delivered.

On Feb. 19, 2004, the Honourable David Anderson, Minister of the Environment, announced Parks Canada’s plan. He was flanked by Parks Canada’s CEO, the presidents of the CAA and CAF, and Justin Trudeau, who gave a moving speech about his brother. Media was everywhere and I was at the table to answer technical questions. Sitting in the front row were several of the parents who’d lost their children in Connaught Creek. Their presence was powerful; our journey together to reach this place had been difficult, and they were there to show their support. It was a very moving experience.

The Minister announced the following five initiatives:

- It would become the law that custodial groups would be led by guides in avalanche terrain.

- Icon-based avalanche warning systems would better communicate the risk to lay-people.

- Avalanche terrain ratings will differentiate between high-risk and low-risk terrain.

- Trailhead signage will provide graphic information about the avalanche risk.

- Environment Canada will contribute $175,000 annually towards a national avalanche centre.

I returned to work to face my colleagues. There were many funny looks and skeptics who said: “We’re going to do what?”

Here is how it went down:

1. ICON-BASED AVALANCHE WARNINGS

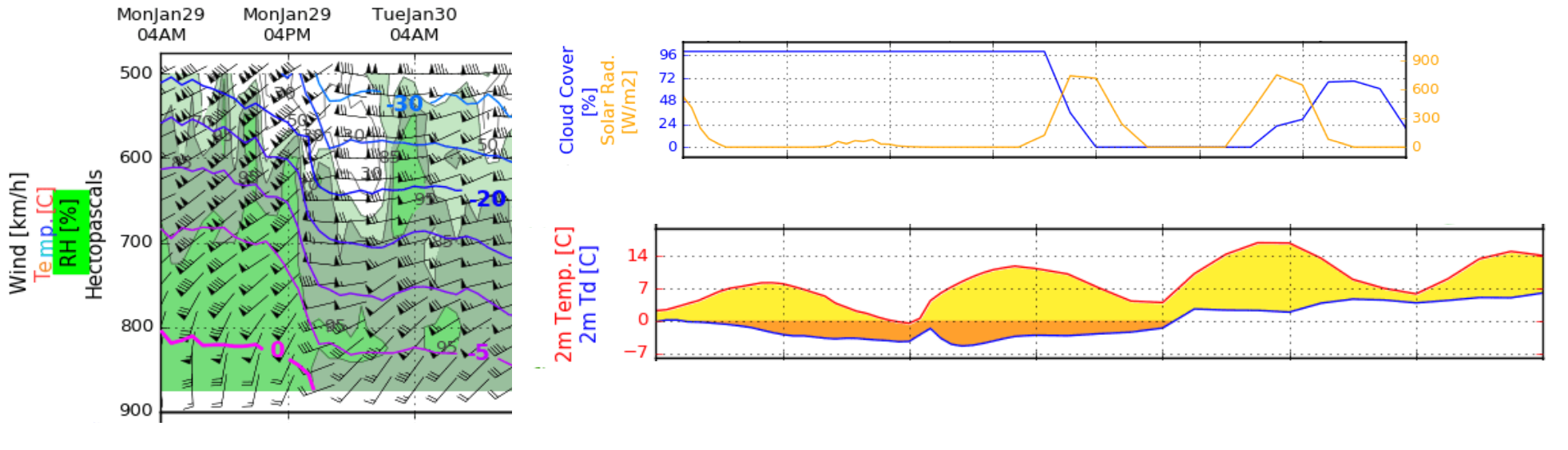

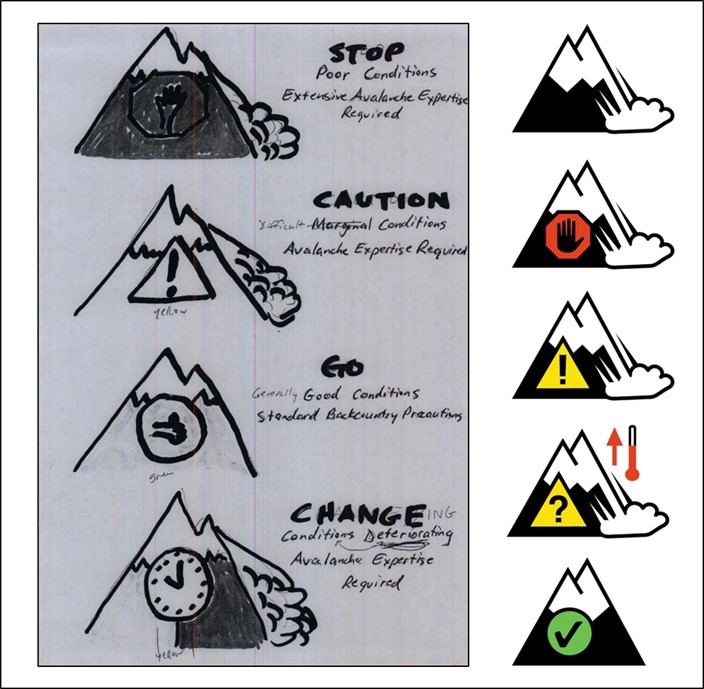

I proposed a single map with icons illustrating the avalanche conditions across all of western Canada. I modelled my ideas after weather forecasters on television, standing in front of a map overlain with sun and cloud icons, waving their hands and pointing—very 1990s. I imagined maps like these in the newspaper too, or icons scrolling across the bottom of a ski resort TV feed. Some people thought my proposal was nuts.

“You can’t communicate the complexities of avalanche hazard with a graphic,” was a common refrain, sometimes followed with an angry accusation of “dumbing down” the system.

We did it anyway. Alan Jones from the CAA and I drew out the first versions (Figure 1) of what would become the Backcountry Avalanche Advisory. We proposed making these icons available using the portal where the mainstream media collected its weather information. The CAA joined the Meteorological Service of Canada’s media portal and by winter 2004-05, icon-based avalanche warnings were in The

Province newspaper every day, alongside temperatures, air quality, and tides.

In 2007, the icons were picked up by the Swiss, who adapted them to fit the European Avalanche Danger Scale. In 2010, when revising the North American Avalanche Danger Scale, we introduced these same icons to make the international standard danger scale icons used today.

2. AVALANCHE TERRAIN RATING SYSTEM

It was pretty obvious to me by reading through the Risk Review and then meeting with a lot of people who didn’t know much about avalanches that we needed a terrain classification method. In fact, I’d pitched this idea to Parks Canada in my job interview. We needed to easily show the difference between a serious backcountry trip and a mellow one. While this might seem like a simple idea today, it was not perceived that way at the time. It seemed like a pipe dream. As forecasters, we had been struggling for years how to better communicate terrain because we knew how important it was, but we were focused on doing that using the avalanche bulletin. Now we were

thinking outside of that box.

I just started, not really knowing where it would go but looking for momentum and help. I made my first draft of the “Avalanche Exposure Scale” (Figure 2) and sent it to my colleagues. They replied with good suggestions and the system improved draft by draft. We modelled it after rating systems like rock climbing or white water and were making progress until the team in Rogers Pass decided it was too simple. They were not prepared to classify avalanche terrain based on my two-sentence descriptors. One day, I opened an email from Bruce McMahon and there was the first version of the ATES technical model. It proposed thresholds for different components of avalanche terrain and provided a reasonable technical basis for rating terrain. I immediately liked it.

But I realized, again, that it was too technical for public warnings. Of course, the forecasters liked it as it met their needs, but we needed something simple for public consumption. That’s when I realized the Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale (ATES) needed to speak two languages: a technical model that met the needs of forecasters and a public communication model that communicated those ratings in a way the public could understand.

By the start of winter 2004-05, the ATES system was finalized and applied to over 275 different backcountry trips in the national parks. We published brochures and a website, and the system was immediately popular. It wasn’t perfect, but it was obvious we had filled a gap. Two years later, we added another 75 waterfall ice climbs. In 2005, working with Pascal Haegeli, ATES became one of the fundamental inputs to the risk assessment method of the Avaluator. These days, who can imagine a risk assessment without the terrain part?

That first version of ATES has stood the test of time. The system has been adopted for many different purposes in many different countries. People use it to zone terrain on maps, apps, risk assessment products, workplace safety protocols, regulations, avalanche education, and more. As the old adage goes: terrain, terrain, terrain.

3. NATIONAL AVALANCHE CENTRE

One recommendation made to both Parks Canada and the Province of B.C. was to support the creation of a national avalanche centre (NAC). This was the birth of Avalanche Canada.

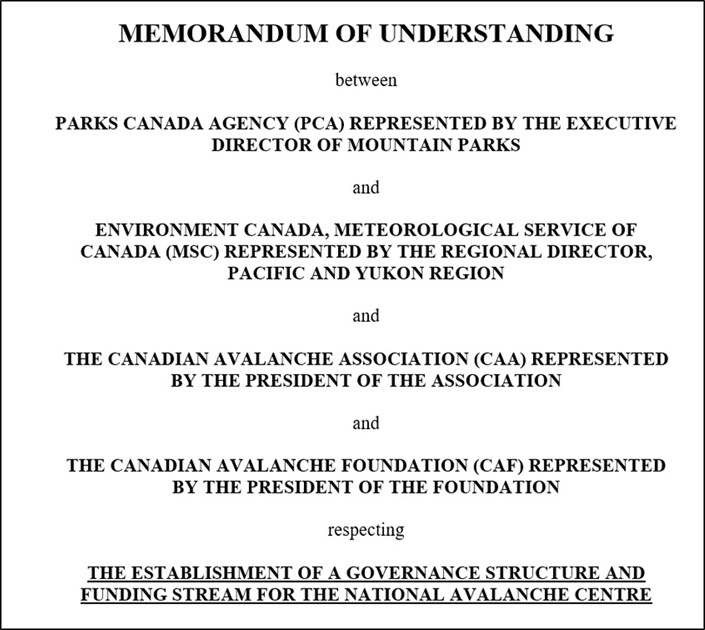

I was Parks Canada’s point-person for this work and we started with a large meeting in Calgary that was attended by all the important stakeholders. Clair Israelson and Bill Mark spoke for the CAA and Chris Stethem for the Canadian Avalanche Foundation. It was obvious the CAA and CAF had the background and knowledge to take on this role, but how?

We signed an MOU (Figure 3) and agreed to build a structure. We hired a governance consulting firm with experience setting up national NGOs. We held meetings, we penned agreements, the CAA proposed a structure, we secured funding, and on Nov. 20, 2004, the Canadian

Avalanche Centre officially opened its doors with a mandate, “To serve as Canada’s national public avalanche safety organization.” A modest budget of $400,000 annually in government funding supplied by Parks Canada, MSC, Alberta and BC would be combined with funding from the CAF.

I could never have imagined the road AvCan would travel to get to where it is today, thanks to its many staff, CAA members, public volunteers, avalanche survivors, government officials, and politicians who have contributed to its evolution. I’m very proud of how it has grown from a grassroots start-up to a robust national organization. Since 2005, the running average of avalanche fatalities in Canada has decreased by over 30%, despite the continuous growth of winter backcountry recreation.

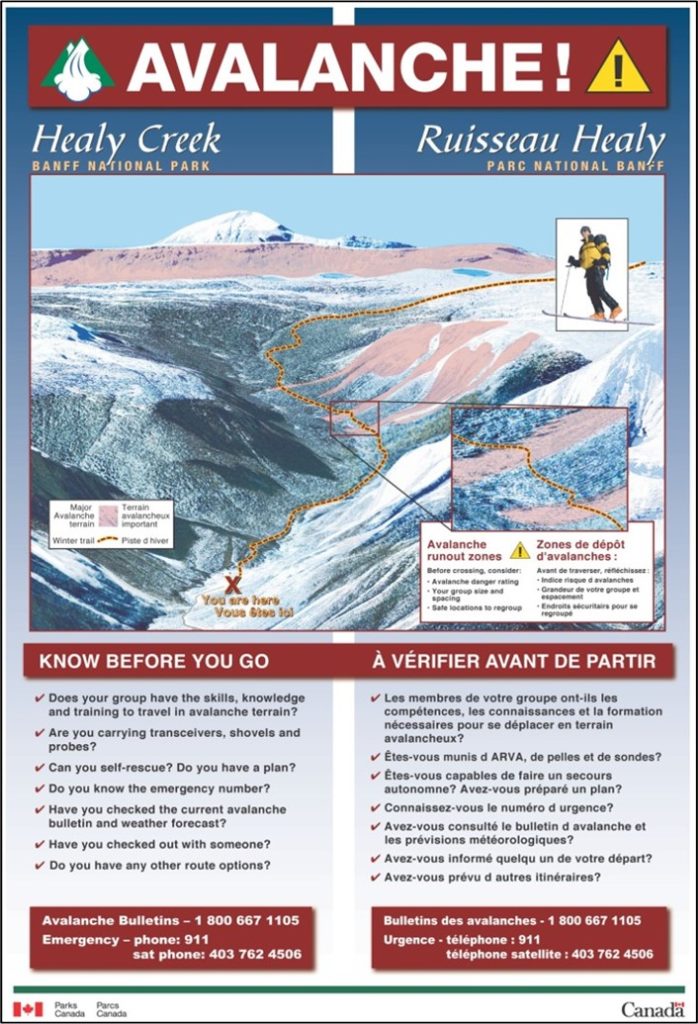

4. AVALANCHE TRAILHEAD MAPPING

For years, CAA professionals had produced avalanche terrain maps for professional use—there was even an avalanche mapping course. I had made avalanche maps for ski areas, highways, forestry, and heli-ski operations. This was essential in order to provide a common reference point to discuss the risk. Who doesn’t like crowding around a run photo to pick the lines, or carefully studying the boundaries of an avalanche path?

We made maps for the public too and developed a list of the most popular winter trailheads in the seven mountain parks. GIS was rudimentary at the time and when I look back at our first grainy images (Figure 4), I cringe, but the idea was to provide a graphic display of the terrain, show it online, and at the trailhead, and accompany these maps with safety messages. The idea has grown, in particular with Avalanche Canada and the Province of B.C. investing in ATES mapping and trailhead signs for many popular snowmobile areas in B.C.

5. CUSTODIAL GROUP REGULATIONS AND POLICY

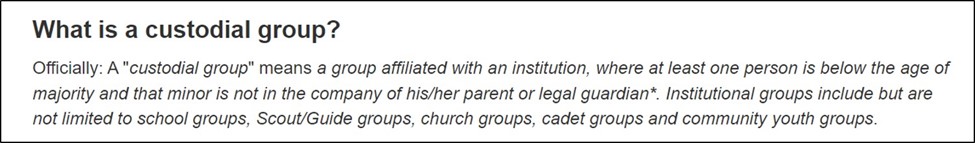

The Risk Review described the legal implications of organized youth groups, or what they called “custodial groups,” travelling in the national park backcountry. They recommended custodial groups be led by a professional guide, “where not-for-profit custodial groups propose to use difficult terrain or use areas presenting high-risk conditions.” In response, Parks Canada’s CEO announced this would become the law.

This was another perfect use-case for terrain ratings, but first we had to define custodial groups (Figure 5). I spent many hours with Glen Marko from the Department of Justice working out a definition that would capture the right groups, without casting too wide a net. Meanwhile, the outdoor education sector was gripped. I was contacted by teachers and educators telling me what a mistake it would be to implement such regulations. They predicted doom for outdoor education and this weighed heavily on me. As a strong believer in getting youth outdoors, I felt an enormous responsibility to get this part right.

We defined custodial groups, built the ATES, and then used both to make it the law that custodial groups be led by a professional guide in ATES Class 2 terrain, and prohibiting travel in Class 3 terrain. Sober stuff, but the coup was that custodial group travel in Class 1 terrain remained unrestricted. Interestingly, once you get beyond the hubris and start looking at the facts, the majority of custodial groups only ever go to Class 1 terrain. It worked—not for everyone, but for the majority. Teachers could continue taking classes into easy, low-risk terrain, and now they even had a list of about 100 different Class 1 trips to choose from. The regulations kicked in when the avalanche terrain became more serious.

2004 and 2005 were the most intense years of my professional life. I left the comfort of a well-established guiding and consulting practice to step into the centre of a tragic mountain disaster. I had no background in government relations or media, little experience with grieving families, and I’d never implemented a regulation or prepared a contribution agreement. I even had to rent a suit the first time I briefed the Minister of the Environment. I was as green as could be in the public sector.

But I had passion, a lot of experience in the mountains, empathy, and a willingness to ask questions and listen to the answers. I discovered my own skill at communication and came to realize the immense importance of respecting and listening to other people who knew nothing about avalanches, but knew about a lot of other things. Any mountain elitism I had was stripped away.

In 2005, Parks Canada made my job permanent and I remained in that position for 10 years. I continued to develop the ideas we started with the Risk Review, which lead to changes to the danger scale, the Conceptual Model of Avalanche Hazard, bilingual avalanche bulletins, and a

universal avalanche bulletin format for Canada, among other things. I honed my skills in policy, writing, and collaboration. By 2013, I felt like my work was done. I had completed what I’d set out to achieve and it was time to go back outside. I resigned from my position after the 10-year anniversary of the Connaught Creek avalanche.

Reflecting back now, I’m very proud of this work and think of the many people who helped me in whatever way they could, most of whom are retired now. That avalanche and the deaths of those children galvanized our community like never before. The relationships I built with their parents, at first fraught with anger and anxiety, evolved to a special place of compassion, respect, and understanding. I will never forget their courage to push so hard for change in the face of such immense grief, and I’ve always wished to dedicate our work to the memory of their children. They really did make a difference.

BIO

In 2003, Grant was teaching avalanche courses and writing avalanche bulletins for the CAA, guiding heli-skiing at Crescent Spur, guiding waterfall ice climbing in the Rockies, and working for Chris Stethem & Associates doing avalanche control for CN Rail and Crestbrook Forest Products. In 2022, he is working for Parks Canada doing avalanche forecasting and control, and search & rescue in Banff, Yoho, and Kootenay National Parks, guiding snowcat skiing at Mustang Powder and ski touring trips, and consulting internationally on avalanche and risk-related topics.